Maria Varnava, the founder of Tiwani Contemporary, a London gallery specialising in artists from Africa and the diaspora, has a long-held fear of financial speculation and bubbles when it comes to the art market.

Working in business development at Christie’s in her 20s gave her an "education in terms of how markets can be built” but also illustrated how a specific market can crash just as fast as it is created, “in a very dangerous way, especially for young artists.” She was at Christie's when “the Indian market went crazy—they were selling things for millions, and then suddenly you could not get those prices. So I was made really aware of the danger of speculation and how one needs to navigate carefully through a purely speculative moment, which, actually, I think is what I'm seeing right now as an organisation”.

This concern was a founding principle of Tiwani Contemporary (Tiwani means “ours” or “it belongs to us” in Yoruba) when Varnava established it in London in 2011. “I was thinking of the ways I would handle the careers of the artists I work with from the commercial side.”

Having left Christie’s after four years, Varnava was studying for a Masters in African studies, with a focus on African art, at London's School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in when she began setting up her own gallery. She’d been given a firm push by the late Nigerian curator Bisi Silva, a pivotal figure in Varnava's career: “I was a big fan of the work of Bisi Silva, who was the founder and director of the Centre for Contemporary Art in Lagos. She was an incredible woman and really empowered artists locally, but unfortunately we lost her to cancer a couple of years ago.” Varnava went to see her in her office in Lagos, seeking advice, explaining that she would like to do a pop-up exhibition of artists from Africa or “a really solid publication”. Silva looked her straight in the eye and said: “You want to do something, Maria, you need to do it all the way. All the way. You need to set up a gallery, and you need to do it properly.”

Artist’s Rendering of Tiwani Contemporary, Lagos

Courtesy of Tiwani Contemporary

So, with some financial backing from her family, Varnava took the plunge, taking a gallery in Fitzrovia, a pricey part of central London, and opening just before her 30th birthday. It was, to say the least, bold considering the high rent that would have to be paid through the sales of "emerging artists that nobody has heard of”, Varnava says. “But I needed to prove myself, put pressure on. I thought, I'm going to have to make it work.” It was, she says, challenging for a few years, not least because she was showing a roster of artists that "broke down any sort of expectation people might have of what art from Africa would look like—for example in my first show, I had a video piece and I think some people were expecting depictions of the Black body. We have never catered to an exotic idea of what art from Africa is about.” Artists who have worked with the gallery since the beginning include Mary Evans, Virginia Chihota, Andrew Esiebo, Theo Eshetu, Dawit L. Petros and Délio Jasse.

African contemporary art has, of course, undergone an enormous boom in interest in the past five years or so, and while such overdue recognition is a good thing, with it comes its fair share of speculators with less than honourable intentions.

Things were very different back in 2011, when artists from Africa were still considered something of a niche interest. Where once the difficulty was in getting collectors to look seriously at the work of artists such as Simone Leigh (hard to believe now), today there is a pressure to protect desirable artists from speculators and flippers. In March this year, No Wahala (2019) by the British-Nigerian painter Joy Labinjo, one of Tiwani’s roster, was flipped at a Christie’s auction in London, where it sold for £150,000. Varnava is clear that the person who bought that work, from Tiwani, will never be sold a painting by the gallery again. “[Flipping] is a problem and Joy’s was my first experience and it was really disheartening, because you do all your due diligence [on the buyer], you talk to other galleries, you do your research, but human beings are unpredictable. You can only do so much.” She adds: “I know cash is cash, but any collector that has placed a work bought from me at auction is definitely not going to be a client of mine again. And they've been made aware. I work with clients that support my programme, that support my artists. I've had to have difficult conversations with Joy because I feel extremely responsible for what has happened.” Labinjo, Varnava says, is philosophical and “understands [flipping] it's not something that’s just happening to her, it's a moment. It's unfortunately happening to a lot of young, mid-career and established artists right now.”

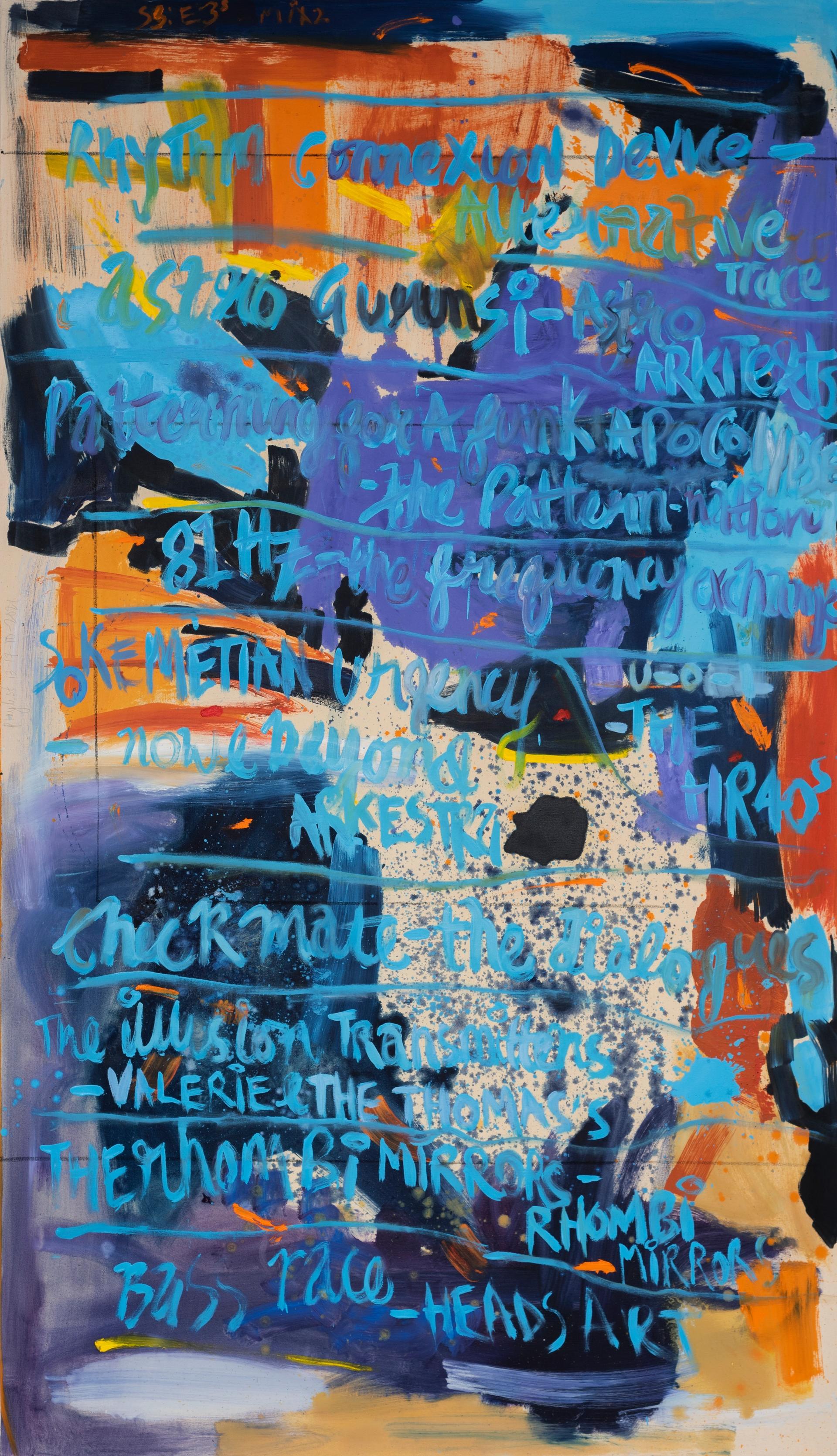

Andrew Pierre Hart's s3:e3s Mix 2 (2021), which will be exhibited at Frieze London

Courtesy of Tiwani Contemporary

Most important to Varnava is the “sustainability” of artists’ markets and careers: “It's a marathon, not a sprint, so I do my research and I’m conservative with prices to safeguard everybody's position.” Tiwani’s sales contracts include a standard 36-month first refusal clause to try to stop clients putting fresh works into auction, but these are hard to enforce.

Poaching of artists is also a challenge that Varnava must contend with as her artists become more desirable and are courted by bigger galleries, keen to quickly diversify their rosters. “It's a shame that artists don't understand the strength they have with a gallery especially when they might leave you because they think they might do better financially with another organisation…they don't necessarily need to be part of a massive machine, you can get lost.”

Varnava’s love of Africa and its culture was born early—she is Greek-Cypriot and, although born in Cyprus, from 40 days old until the age of 11 she grew up in Lagos, Nigeria, where her father still has a construction company. “I spent my formative years in Nigeria and, having young children now [Varnava has three under six], I realise it really shapes you, that time of your life,” she says. “The people I was growing up with, the art, the visual language I was growing up with and exposed to was that of Nigeria.”

And so, in February 2022, Tiwani Contemporary will open a 2,000 sq ft purpose-built gallery in Victoria Island, Lagos—it was always Varnava’s plan to open in Nigeria in the gallery’s tenth year. “It's like a homecoming for me, to a place that I love, where I had the most incredible childhood,” Varnava says. “I'm very excited by the number of galleries that are opening in Nigeria, the number of artist-led initiatives like residencies. What I've noticed in the past few years is that entrepreneurial, driven young Nigerians are choosing to return home whereas, back in the day of my parents, most of them chose to stay in the US or UK or wherever they were studying. So, I think that energy is electrifying and super exciting.”

Warriors Inhabit Mind Body and Spirit (2021) by Charmaine Watkiss

Courtesy of Tiwani Contemporary

Working with artists from Africa and the diaspora means Tiwani needs to be on the continent, Varnava says: “Especially in the early days, I was selling a lot to a few incredible European and US collectors. That’s great, but it’s also problematic for me because I would love to see more African, pan-African and continent-based collectors supporting artists from Africa in the diaspora. I think that would make the market more sustainable, if there was more local patronage.”

While the Lagos exhibition programme will predominantly focus on Tiwani’s own artists (“It means a lot to our artists to show their work on the continent”), Varnava also wants to show a broader mix, “to bring to Lagos international artists, so students from the local art school will be able to see, in person, international contemporary art.” The space will open with a solo exhibition of the work of Labinjo, as she “has links to Nigeria and feels, in the same way as I do, a sense of a homecoming”.

Next week, Tiwani will exhibit at Frieze London with a solo-booth of paintings, sound pieces, drawings and text works by the London-based artist Andrew Pierre-Hart, whose work is currently on view in Mixing It Up: Painting Today at London’s Hayward Gallery. Meanwhile at Cromwell Place during Frieze week, the gallery will stage an exhibition of work by the Congolese-Australian artist Pierre Mukeba and, in November, plans a debut solo show of a new series of drawings by the London-based artist Charmaine Watkiss, titled The Seed Keepers, which according to a statement “fuse Watkiss' interests in botany, herbalism, ecology, history, and Afrofuturism”.

In the last three years, Varnava says, the gallery has gained confidence, things have gotten easier as its reputation has matured and spread. “When I was setting up the gallery, it was in the early moments of the incredible energy we're seeing now—it was before the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair started, before Tate had its Africa acquisitions committee—and I was doing something quite bold. I wanted to be in central London, I didn't want this African-led initiative to be in the outskirts. Sometimes I thought, is it worth it. But thankfully, hard work and resilience paid off.”

Perceptions and reputations can change fast and, as Varnava says: “It’s funny to think that in 2013, I was working with Simone [Leigh] and Njideka [Akunyili Crosby] and I had to persuade people to look at them. Now look at them!”.