Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror

Until 13 February at the Whitney Museum of American Art, 99 Gansevoort Street, Manhattan

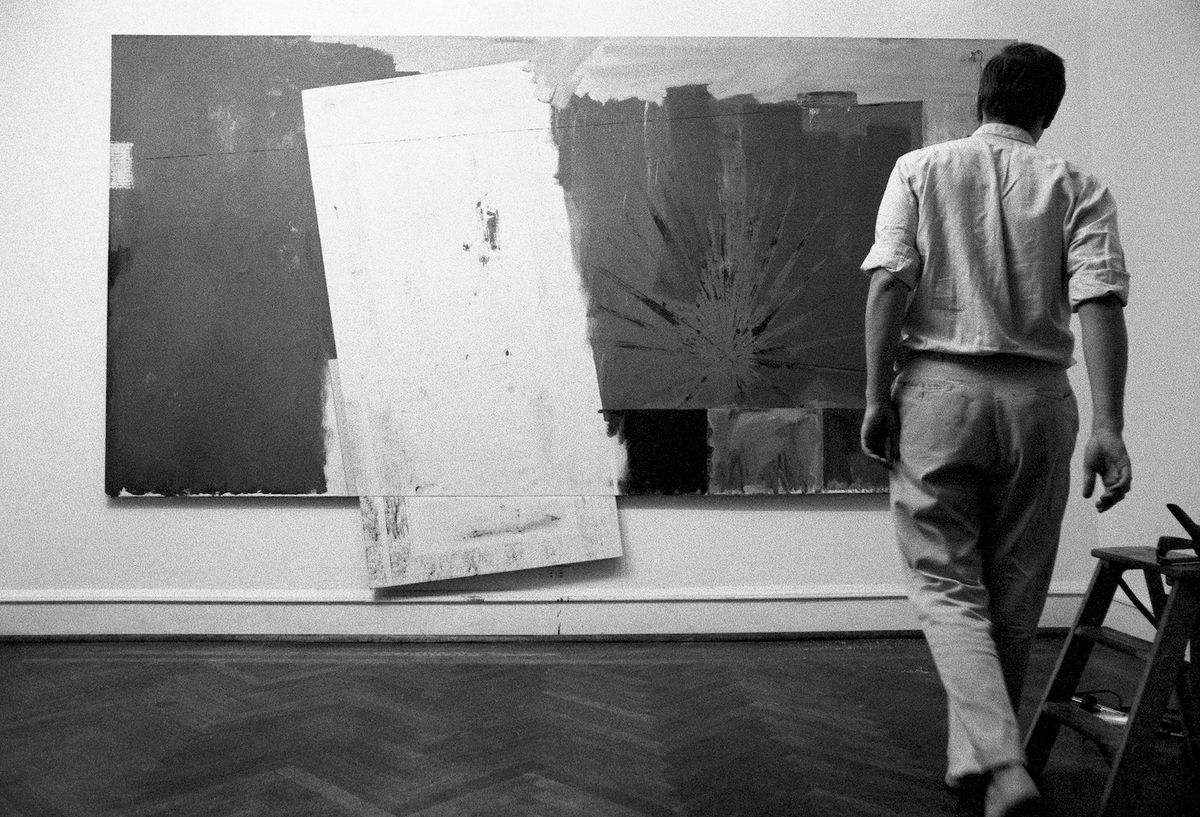

The two-venue retrospective devoted to Jasper Johns, on view simultaneously at the Whitney and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, is envisioned as a single exhibition, with galleries at each venue exploring variations of related subjects (for example, a section devoted to “dreams”, or surreal Picasso-inspired images, is paralleled with a “nightmare” section at the PMA). The show celebrates the artist’s prolific and ever-evolving practice, including some previously unseen works by an artist whose career is already firmly planted in American art history. From his ubiquitous encaustic and metal works depicting US flags and numbers to the stick-figure spectres prevalent in his works after the 1990s, which represent meditations on death, the exhibition explores the motifs that became points of obsession for Johns at various periods in his career. Perhaps the most intriguing part of the exhibition is a room dedicated to archival documents and photographs, which chronicles the Whitney’s long relationship with Johns. It includes a press release for his 1978 retrospective at the museum and an “artist questionnaire” on the philosophy and materials and methods behind the work Studio (1964)—the first of more than 220 works that the Whitney has acquired by the artist.

John Chamberlain, Tambourinefrappe (2010). Photo: © 2021 Fairweather & Fairweather LTD / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy Gagosian.

John Chamberlain: Stance, Rhythm and Tilt

Until 11 December at Gagosian, 522 West 21st Street, Manhattan

The career-spanning exhibition marks the first major presentation of John Chamberlain’s enigmatic crushed steel sculptures since his retrospective at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 2012. Like the retrospective, the show has been organised by the eminent curator Susan Davidson, a friend and scholar of the late artist. “John was attentive to the toughness and physicality of his work—he was a real dude,” Davidson says. Chamberlain’s use of material and focus on scale was heavily influenced by his three-year term in the US Navy and his observation of the commanding power of industrial machinery. “He once said that if you get the scale right, the size doesn’t matter,” Davidson adds. The show comprises a series of automobile armatures that dwarf the viewer with their raw and undoubtedly masculine presence. For example, the massive Tambourinefrappe (2010) amalgamates a vintage car with strips of painted chrome-plated steel. The works visually and linguistically invite scrupulous consideration. Each is poetically and sometimes humorously titled, echoing Chamberlain’s study of poetry at Black Mountain College in the 1950s.

Installation view of Mandala Lab at the Rubin Museum of Art. Photo: Rafael Gamo. Courtesy of the Rubin Museum of Art.

Mandala Lab: Where Emotions Can Turn to Wisdom

Long-term installation at The Rubin Museum, 150 West 17th Street, Manhattan

Last summer, the Rubin Museum announced that it would clear its third-floor galleries of Himalayan art to construct the $1m “Mandala Lab”, a long-term exhibition that aims to merge Buddhist principles with interactive installations conceived with contemporary artists like Laurie Anderson and Sanford Biggers. The ambitious project, which opens this week, feels incongruous with the museum and its inimitable collection, seeming to cater to children dabbling in Eastern philosophy. Visitors first encounter a series of scent-emitting machines, each complemented with a video of an artist recounting memories of particular scents (Anderson on cigarette smoke; Biggers on temple incense). Rather than soothe the senses, the scents linger pungently in the air. At the cost of some gems from the Rubin’s collection being relegated to storage, there is life-affirming signage throughout the floor; a glowing mandala-like sculpture at the centre by Palden Weinreb where visitors are encouraged to practice breathing exercises; and a series of gongs that can be struck and submerged in water, creating trippy sounds.