Appropriation art, the practice of using pre-existing elements or images in a new work while making few or sometimes even no alterations to the original work, has been a subject of legal controversy for many decades.

Scholars and judges have extensively commented on the obvious tension between copyright law and Appropriation art, where “from the perspective of copyright law the very term ‘Appropriation Art’ is a provocation; ‘appropriation’ of protected work connotes stealing”.

Some celebrated artists who form part of the Appropriation art movement and happily embrace the title of “provocateurs” include Richard Prince, Jeff Koons and Andy Warhol. The works of these artists have been at the centre of recent court cases that have tried to draw the line between permitted appropriation and unlawful copying.

Due to the fact-intensive nature of this enquiry and the territorial nature of copyright law, court decisions on this issue have arguably yielded inconsistent outcomes, leaving stakeholders confused and frustrated. Conflicting jurisprudence runs the risk of chilling artistic expression, especially of those who cannot afford protracted and expensive court battles.

Andy Warhol Foundation for Visual Arts versus Goldsmith

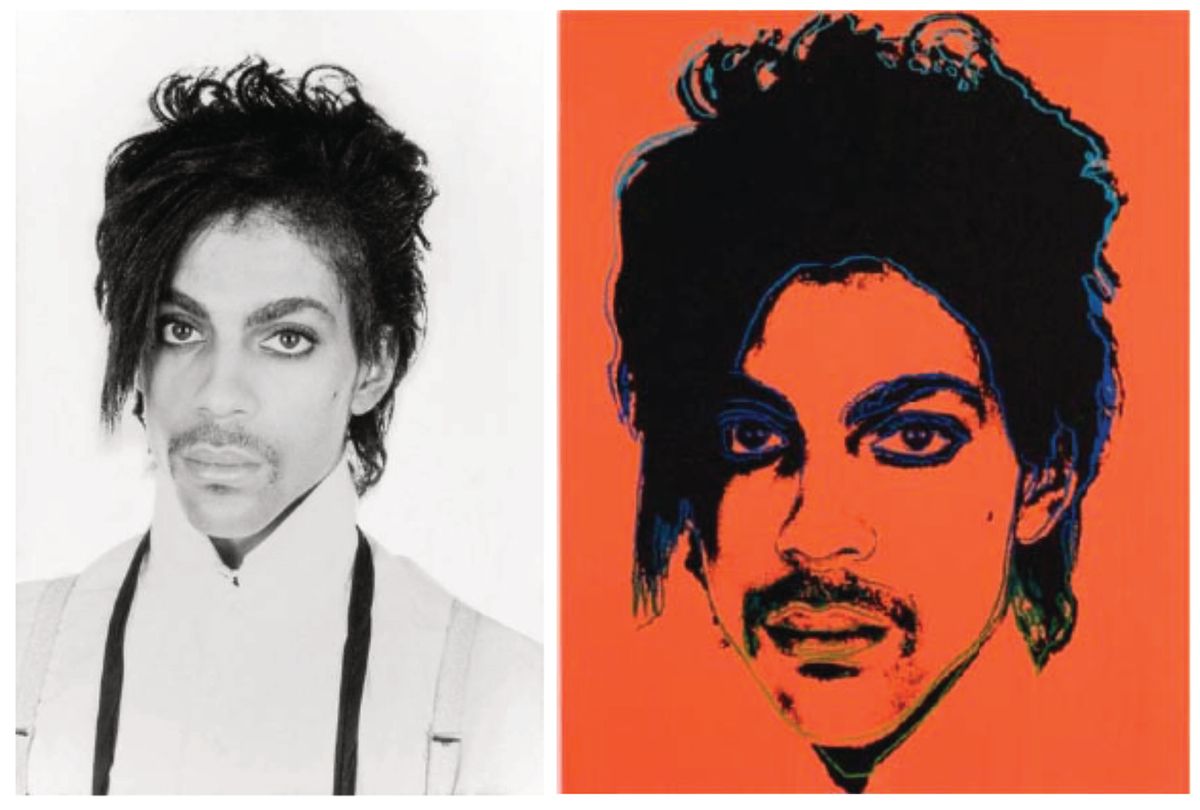

Most recently, on 24 August, the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit issued a scathing amended decision in the dispute between the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and photographer Lynn Goldsmith, finding that Warhol’s Prince Series infringed upon Goldsmith’s copyright and did not make fair use of Goldsmith’s photograph.

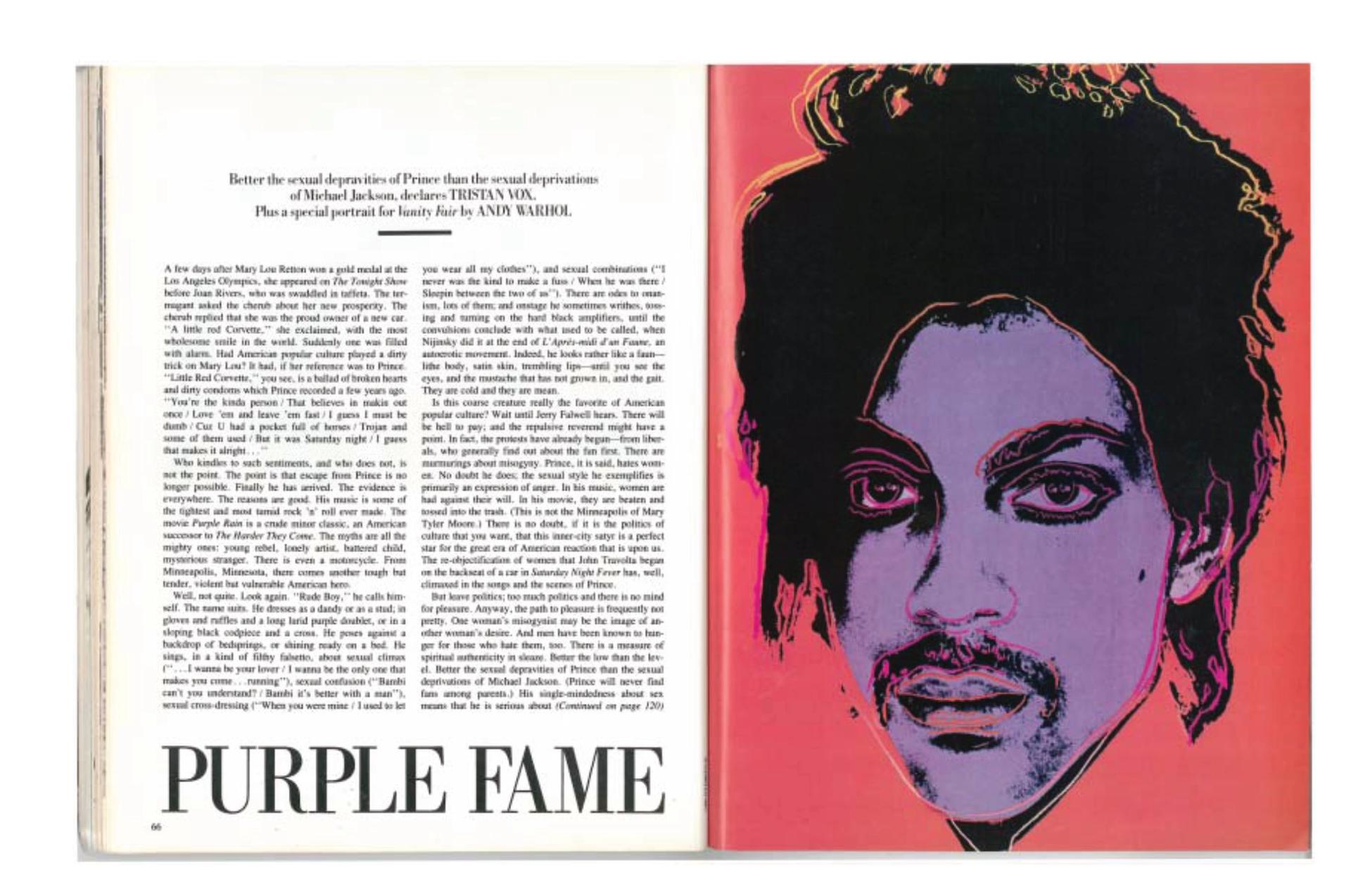

In or around 1984, Goldsmith’s photograph of the iconic musician Prince was licensed to Vanity Fair magazine, which commissioned Warhol to create an artwork using Goldsmith’s image. Warhol later used Goldsmith’s photograph to create 15 additional unlicensed works which together became known as the Prince Series. Goldsmith only learned about the unlicensed use of her photograph by Warhol in 2016, after Prince’s death, and notified the Warhol Foundation of the alleged infringement of her copyright. A court battled ensued.

Andy Warhol obtained Lynn Goldsmith’s photograph of Prince from Vanity Fair, which had commissioned him to make an illustration of the singer that, as provided in Goldsmith’s license, would be published in the November 1984 issue only

Photo source: Court documents

In making its determination, the Second Circuit focused on the fact that the Prince Series was not sufficiently transformative of Goldsmith’s photograph as, according to the Court, the Prince Series lacked “a fundamentally different and new artistic purpose and character” from the original photograph and on the fact that the Prince Series “pose[d] cognizable harm” to Goldsmith’s market to license the photograph. The Court also felt “compelled” to clarify that “it is entirely irrelevant to [the fair use] analysis that ‘each Prince Series work is immediately recognisable as a Warhol’”, as “entertaining that logic would create a celebrity-plagiarist privilege” where the more established the artist the greater the freedom to copy.

Artistic or utilitarian purpose?

In April 2021, the US Supreme Court issued a decision in a dispute between Google and the tech firm Oracle, finding that Google’s use of Oracle’s software code in its Android operating system—that was clearly recognisable as Oracle’s—constituted fair use. In light of this Supreme Court decision, the Warhol Foundation requested a rehearing of its case. The Foundation argued that the Google decision undermined the Second Circuit’s opinion in the Warhol dispute because the Supreme Court found Google’s use to be fair even though Google’s code contained Oracle’s copyrighted material that was obviously recognisable.

In its amended decision, the Second Circuit rejected the Foundation’s assertion and held that the Foundation misinterpreted not only its decision but the Supreme Court’s decision, where the Supreme Court made a clear distinction between use that was artistic in nature versus use that served a utilitarian purpose. The Second Circuit quoted the Supreme Court emphasising that “copyright’s protection may be stronger where the copyrighted material ... serves an artistic rather than a utilitarian function” and “[t]he fact that computer programs are primarily functional makes it difficult to apply traditional copyright concepts in that technological world.”

The Second Circuit concluded that “just as artists must pay for their paint, canvas, neon tubes, marble, film, or digital cameras, if they choose to incorporate the existing copyrighted expression of other artists in ways that draw the original work’s purpose and character . . ., they must pay for that material as well.”

Cariou versus Prince et al

Some have argued that the Warhol decision by the Second Circuit squarely contradicts its 2013 decision in Cariou v. Prince et al., where it held that 25 of the 30 works of art by Richard Prince that formed part of his Canal Zone Series made fair use of Patrick Cariou’s photographs in Yes Rasta. Of course, unlike the 25 works in the Canal Zone Series, where Prince “unmistakably deviated from Cariou’s photographs”, according to the Warhol Court, the Prince Series “only magnified some elements of Goldsmith’s photograph and minimised others”, where the Goldsmith photograph “remain[ed] the recognisable foundation upon which the Prince Series is built.”

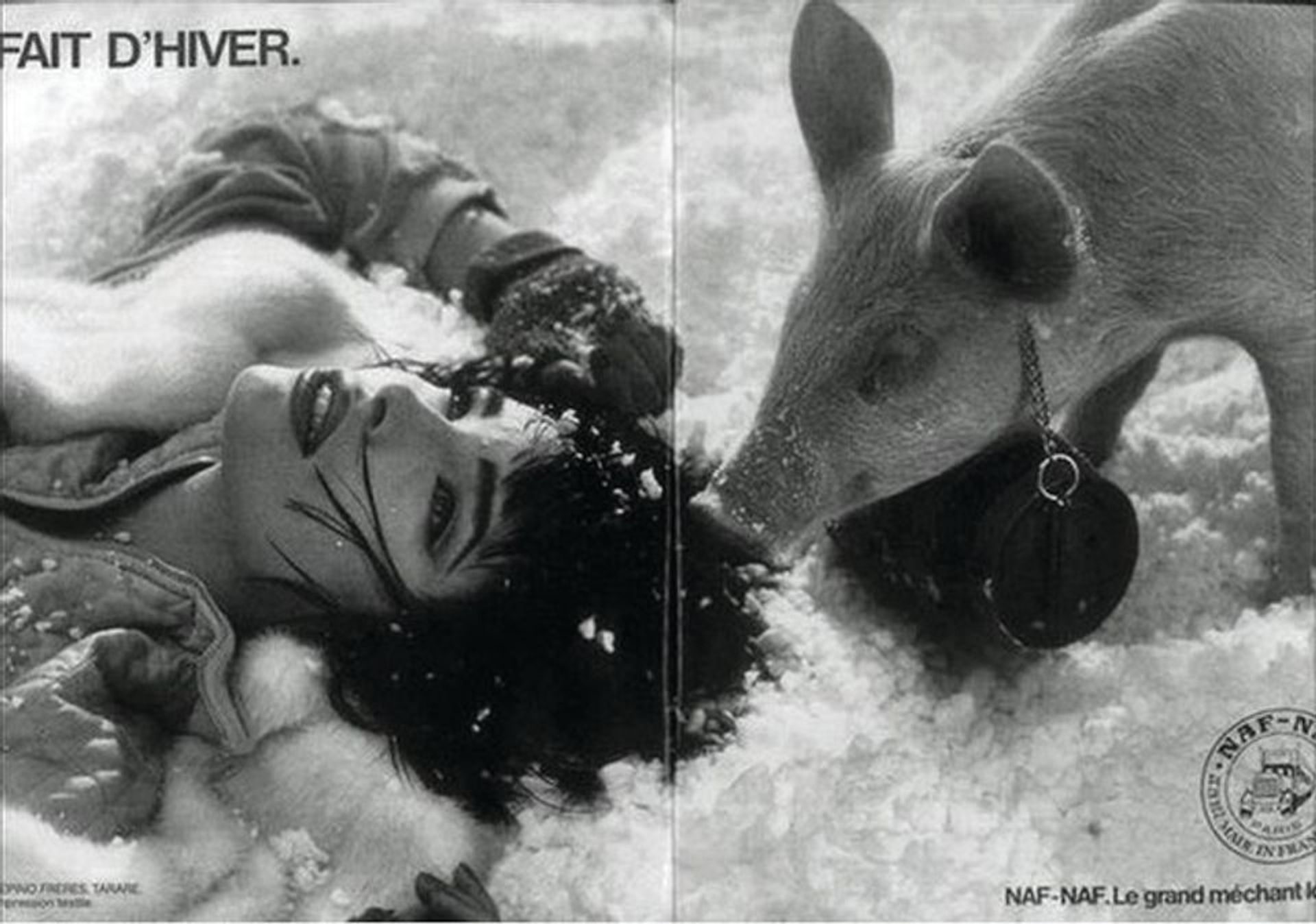

Naf Naf advert by Franck Davidovici, 1985.

Image: Naf Naf

Humourless: Davidovici versus Koons

Matters are further complicated when considering the copyright framework in Europe, where there is no fluid or dynamic doctrine of “fair use”. Rather there exists a closed-catalogue list of statutory exceptions to copyright infringement.

This is highlighted in a recent Paris Court of Appeal judgment in a dispute involving Jeff Koons, who created a sculpture borrowing from a photograph of a Naf Naf advertising campaign created by the artistic director Franck Davidovici. In his defence against Davidovici’s claim of copyright infringement, Koons relied on France’s parody exception to copyright infringement and argued that his freedom of artistic creation should prevail over Davidovici’s property rights. The Court of Appeal rejected Koons’s argument that his sculpture fell within the parody exception on the grounds that his work did not demonstrate humour or mockery, nor did he make any reference to or comment on Davidovici’s photograph which the Court deemed essential to qualify as a parody. In concluding that Davidovici’s copyright should prevail over Koons’s freedom of artistic expression, the Court also took into consideration Koons’s message (which was artistic, as opposed to political or otherwise in the public interest), the commercial nature of Koons’s work and his prime position in the art market (which, according to the Court, made his omission to seek a license from Davidovici to reproduce the photograph unjustified).

Protecting the rightsholder versus innovation: the difference between the French and the US approach

As demonstrated by this case, Appropriation artists enjoy little flexibility before the French courts. This is for two reasons. First, artists are forced to conform their use of copyrighted works within a closed list of exceptions, the most relevant of which is parody, even if they may not have meant for their works to be parodies or would have preferred to leave such interpretations to the public. Second, French courts lean towards the preservation side of the balance, placing greater emphasis on protecting the rightsholder’s property rights. This is in sharp contrast with the US copyright framework which values innovation and has a relatively fluid fair use test to assess whether a work infringes upon another’s copyright. Whereas the French Court paid great attention to Koons’s witness statement about his intent behind the work, the US Second Circuit’s position in Cariou makes clear that “what is critical is how the work in question appears to the reasonable observer, not simply what an artist might say about a particular piece or body of work”.

Fait D'Hiver (1988) by Jeff Koons

Photo by Ralph Orlowski/Getty Images

No uniform global copyright law

While art is now enjoyed at an accelerated pace and on a global scale, there are no uniform copyright rules and regulations that govern its use or consumption. This means copyright protections enjoyed by a copyright owner in one country do not automatically apply in another and local law must be considered. Appropriation artists who do not have deep pockets must be careful about how they make their art and where they choose to exhibit and/or reproduce it. Equally, museums and collectors who collect art by artists who use copying as both the subject of and a tool for their creation must also be wary, as they too may be accused of copyright infringement for exhibiting a work.

Increasingly, collectors and museums are asking artists to sign sale contracts that contain an indemnity provision to protect them against claims of copyright infringement, fairly or unfairly shifting the burden of such claims to the artists.

As evidenced from the case law above, drawing a line between permissible use and copying is hardly straightforward not least because this is an ever-evolving area of the law that is often guided by cultural norms, market forces and the subjective beliefs of judges, and where applicable, juries. As the Warhol Court aptly put it, “[c]opyright law does not provide either side with absolute trumps based on simplistic formulas. Rather, it requires a contextual balancing based on principles that will lead to close calls in particular cases.”

This line will again be tested in the ongoing six-year long litigation between Richard Prince and photographer Donald Graham, in which Graham has accused Prince of copyright infringement for reproducing his photograph in Prince’s Instagram Series with limited alterations and without consent. If the Warhol case is any indication, Prince has an uphill battle to prove that he made fair use of Graham’s image.

- Azmina Jasani is a Partner in the Art and Cultural Property Law Group of Constantine Cannon. She represented Gagosian Gallery in the Cariou v. Prince and Gagosian Gallery litigation before the US federal courts. Emelyne Peticca is an Associate in the Art and Cultural Property Law Group of Constantine Cannon.