“The people who deal in antiquities—and we’re talking about a socio-economic strata that you and I can never hope to attain, with their limousines waiting at the curb and with their bespoke suits—are capable of the same base criminality as common hoodlums in the streets of lower Manhattan. For me, honestly, they’re just the same.”

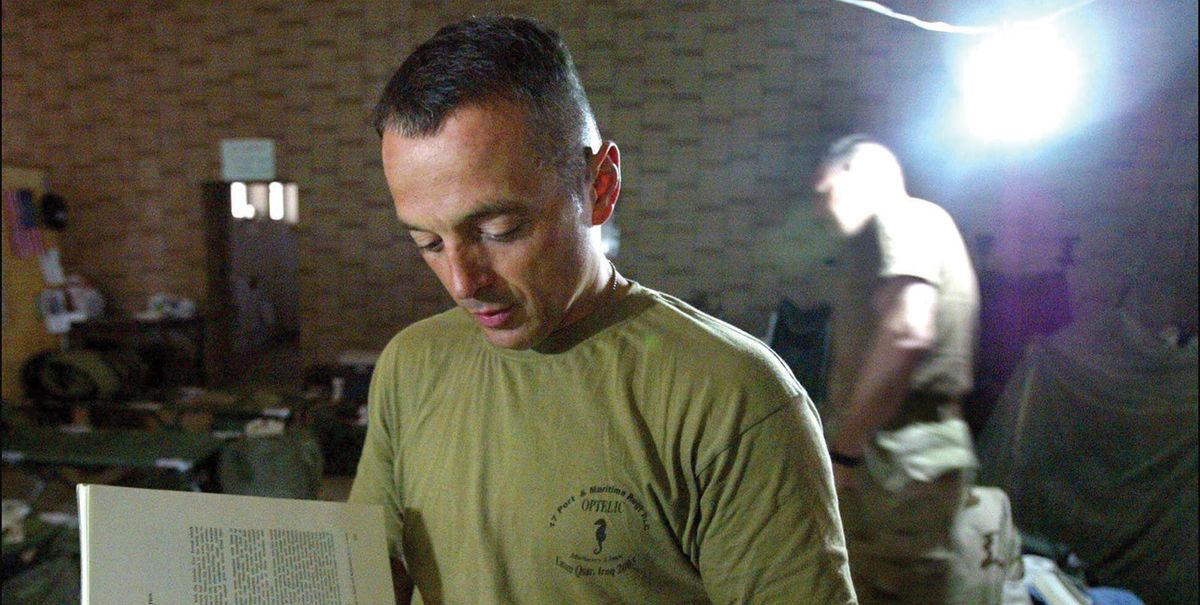

This is what Matthew Bogdanos, the Manhattan assistant district attorney, the head of the New York Antiquities Trafficking Unit and former marine colonel, told me when I interviewed him for my podcast series Art Bust, about crimes and scandals in the art world. It was hardly an earth-shattering observation, just the typical put-down of white-collar crimes by a tough-talking cop.

I don’t agree with him. As I made the series, I had the growing sense that there was something different about the mindset of the art detective and the art crook, even if I found it elusive to define. Sure, the art detective, like any other detective, likes to take the moral high ground and gets a kick out of getting the bad guys. There is a contempt, which I have recognised among other kinds of detectives on white-collar crime cases, for the airs, graces and activities of their wealthy targets, such as that familiar figure, the international antiquities scholar-dealer-smuggler, whether it be the late Douglas Latchford, charged by US authorities in 2019 with trafficking looted Cambodian antiquities, or Subhash Kapoor, indicted by the US in the same year for running an international smuggling ring for more than $143m worth of Indian and Asian antiquities. Just like other detectives today, the art cops will engage the relevant communities if the crime has wider cultural implications. So when the FBI raided the basement of the collector Don Miller and found in his private museum not only Chinese antiques and Pre-Columbian pottery but also the human remains of hundreds of native Americans, dug up from sacred burial sites, they consulted native American organisations about how to handle what they found.

The art detective believes he is fighting against crimes which are being committed against a culture in its entirety

But the art detective today differs even from the art detective of yesterday. Until recently, art crime was considered a low priority and a victimless crime. It was just rich people ripping each other off. Art crime squads were under-resourced. A job in the department was a way of putting someone out to grass. It was all about helping rich people get their stolen snuff boxes and Meissen porcelain back. This view was demolished by top-level detectives such as Vernon Rapley, who led Scotland Yard’s Art and Antiques Squad between 2000 and 2010. Now art crime is a way gangs launder their money. Looting antiquities is a way terrorists fund their operations. Stop the art crimes, and you put a spanner in the cogs of something much bigger.

Philosophical conception

But today’s art detective has a larger, even a more philosophical conception of his mission. Detectives conceive of the victims of crime primarily as individuals, but the art detective believes he is fighting against crimes which are being committed against a culture in its entirety. Looting antiquities is a crime that erases a country’s history, thereby damaging the identity of a people, and destabilising their society and civil institutions in the present. Art is a barometer of the health of society, and therefore it is of value in itself to defend it against forgers and fraudsters. We are familiar with the term “crimes against humanity”, which have been prosecuted since the aftermath of the Second World War, but we may now be seeing the embryonic emergence of a new category: “crimes against culture”.

Perhaps, though, you might think this is all rather predictably self-interested. Have the cops merely fallen for the myth of the higher importance of art peddled by the art world itself?

Inigo Philbrick, who was arrested last year and is currently awaiting trial for fraud in the US, with Francisca Mancini Photo : Stuart C. Wilson/Getty Images

Well, if this is the case, the (alleged) art crooks are guilty of the same sin. There is plenty generic to find in them, too, of course. Inigo Philbrick, the high-flying art dealer currently sitting in a US jail charged with fraud, might prove to be like other millennial con artists such as Anna Delvey and the Fyre Festival organisers, seduced by the glamour, convinced they didn’t do anything everyone else wasn’t or isn’t still doing. On the other hand, art thefts are often carried out by organised crime gangs, whether it is the Johnsons in the UK, the mafia in Italy or Dutch drug cartels. The forgers are often unsurprisingly working-class, poor, down on their luck, with a grudge against society.

But like the art detective, the art crook believes they are serving a higher purpose. The successful forger believes he is dismantling the phoney values of the art world and cocking a snook at its snobbery. The antiquities trafficker will tell you that if they didn’t get the artefacts out of this or that war-torn and failed state it would crumble through neglect or be destroyed by an extremist militia. Even the fraudulent art dealer with his ponzi scheme fantasises that he is shuffling his debts around for the long-term benefit of the reputation of the great, currently under-appreciated artist whose market he is invested in.

There is always this sense, to coin a phrase, that the art justifies the means. It’s okay for us to do it—but not for people outside the fantastical, privileged realm of art.

• Ben Lewis’s Art Bust is available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify and the usual podcast platforms. His book The Last Leonardo is published by William Collins, UK (£9.99, pb) and Ballantine Books, US ($28, hb)