Private art museums have become a cultural, social and economic phenomenon of this century; their number has proliferated across the world. They are the way deep-pocketed collectors give the public access to their art treasures or offer a platform for art and artists—sometimes in spectacular, architect-designed buildings, more occasionally in their own homes. They are a way of “giving back to society” through educational and outreach programmes, bolstering the cultural credentials of the region, supporting local artists—and leaving the legacy of the founder’s name and public-spiritedness for future generations.

Norwegian collector Christen Sveaas established his private museum The Twist on the Randselva river outside Oslo © Arvid Hoidahl

In the past, collectors probably were content with supporting their local institution, writing cheques, serving as trustees and finally bequeathing their art on their passing. Not so today. So why are so many more building their own museums?

According to the London-based wealth manager Steven Kettle, a partner at Stonehage Fleming, who advises clients on succession planning: “Their number one consideration is to keep the collection together.” And, he adds, “They don’t like giving up control.”

This question of control is key. Today’s art collectors, those who have established their own museums, have often made their money themselves rather than inheriting it. They are accustomed to making their own decisions, they have created the collection and they want to manage it.

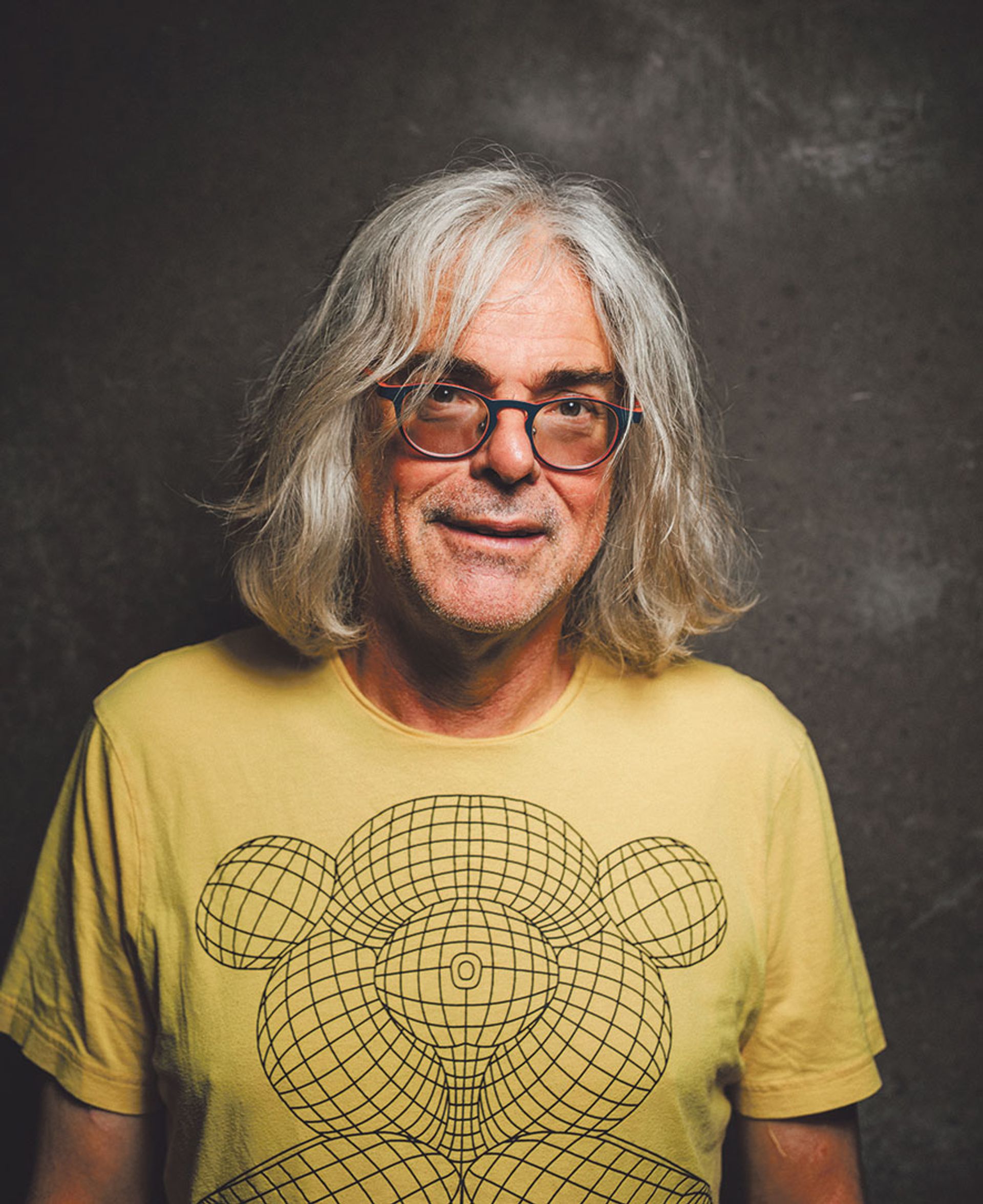

Tasmanian collector David Walsh wanted to absolve himself from “feeling guilty about making money without making a mark” Photo: Mona/Jesse Hunniford; courtesy of Mona

Relinquishing power goes against their fundamental instincts. “Giving to a public institution represents loss of control and I suspect that is the thing that makes collectors stay their hand more than anything else,” says the cultural consultant Adrian Ellis. “When museum directors talk to potential donors, the latter will ask questions such as, ‘Will it be deaccessioned, will it have its own separate space, and will it have my name on it?’. Public institutions are reluctant to meet these conditions because of their own internal policies—so pretty soon the collector thinks, ‘Why don’t I have some fun now and make my own museum?’”

Disappearing acts

An astonishing admission comes from Mark Jones, the former director of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. He told me: “Well, you’d be pretty mad to give it to the British Museum or the Victoria and Albert. Because what will happen is that it will disappear over time. Some of these museums are in the habit of breaking [the terms of] people’s wills. They know they can do this and, in the end, they do.” He adds: “The idea that you’re going to have a gallery permanently in your name, it’s an illusion. You might have it for a bit, but after a while it too will disappear.”

Then there is the question of trust. Collectors fear that public institutions might not treat the collection as they would, nor conserve it correctly and keep it on display. In the US, there is the added concern, among donors, that a work of art could be deaccessioned. Such are these fears that Doris and Don Fisher, the founders of The Gap clothing brand, kept a firm rein on the loan of their billion-dollar collection of contemporary art to San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) in 2010. They put extraordinarily stringent conditions on the loan of over 1,000 works to SFMOMA, stipulating that the loan would be for 100 years, renewable for another 25, after which their descendants would decide on the fate of the collection. Will these conditions be respected? Most of us will not be around to find out.

The question of control is key. Today’s art collectors are accustomed to making their own decisions

Two things are exacerbating this breakdown of trust. One is the perfectly laudable desire of museums to reflect diversity. They started selling works that had been donated, sometimes by the artists themselves, to buy works by women and artists of colour. And then many US museums eagerly took advantage of the relaxation of rules on deaccessioning during the pandemic to bolster their finances. Donors today may well wonder if museums will want to monetise their gifts in this way in the future…

Another motivation is “giving back to the community”—variations on this was the reason most cited by the museum founders I met. The Norwegian collector Christen Sveaas explained why he had established his private museum The Twist outside Oslo. “I believe if you have been successful, then you should help others to be successful, that is the greatest happiness,” he told me. “It was to justify that I’ve been lucky—and to give something back.”

Making artists visible

Then there is a genuine desire to give a platform to contemporary art and artists in nations where the government cannot fund contemporary art museums. In countries such as India, Indonesia or Bangladesh, private museums are essential to give contemporary artists visibility in the absence of government support and interest. In Italy, public institutions largely ignore contemporary art, leaving foundations such as the highly acclaimed Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in Turin to fill this gap. And, in many cases, such museums also run educational programmes, making up for the lack of such provision in the state sector.

There may be other, more complicated, elements at play. In the case of founders who have come from modest backgrounds, they are now able to “share” their good fortune with the public. They have succeeded, and the outwardly visible signs of their riches are their art collection and the other toys of success.

Christen Sveaas wanted to “give something back” and “help others to be successful” Photo: Ivar Kvaal

This aspect cannot be underestimated, alongside an often healthy competitiveness. The Belgian collector Walter Vanhaerents even saw other collectors as rivals and told me that “there is a fight” to get the best pieces. One of his main motivations, in setting up his own art space, was gaining better access to the works of art he wanted.

Then there is the desire to leave a legacy—David Walsh, who established the Museum of Old and New Art (Mona) in Hobart, Australia, wrote in his 2014 biography, A Bone of Fact: “Winning gamblers [like himself] end up with money but have achieved nothing else. It’s fair to argue that I built Mona to absolve myself from feeling guilty about making money without making a mark.”

Finally, and this particularly applies to the US, there are juicy tax breaks for the founders of private museums through 501(c)(3) foundations, a subject investigated and sharply criticised by Senator Orrin Hatch in 2016. While no one doubts that the overall cost of building your own museum far outstrips the amount saved on tax, it does sweeten the pill.

The problem here is that many argue that those missing tax dollars might have benefited public institutions, rather than allowing some billionaires to profit from what are often derided as self-aggrandising vanity projects.

• The Rise and Rise of the Private Art Museum, Georgina Adam, Lund Humphries, in partnership with Sotheby’s Institute of Art, 104pp, £19.99 (hb)