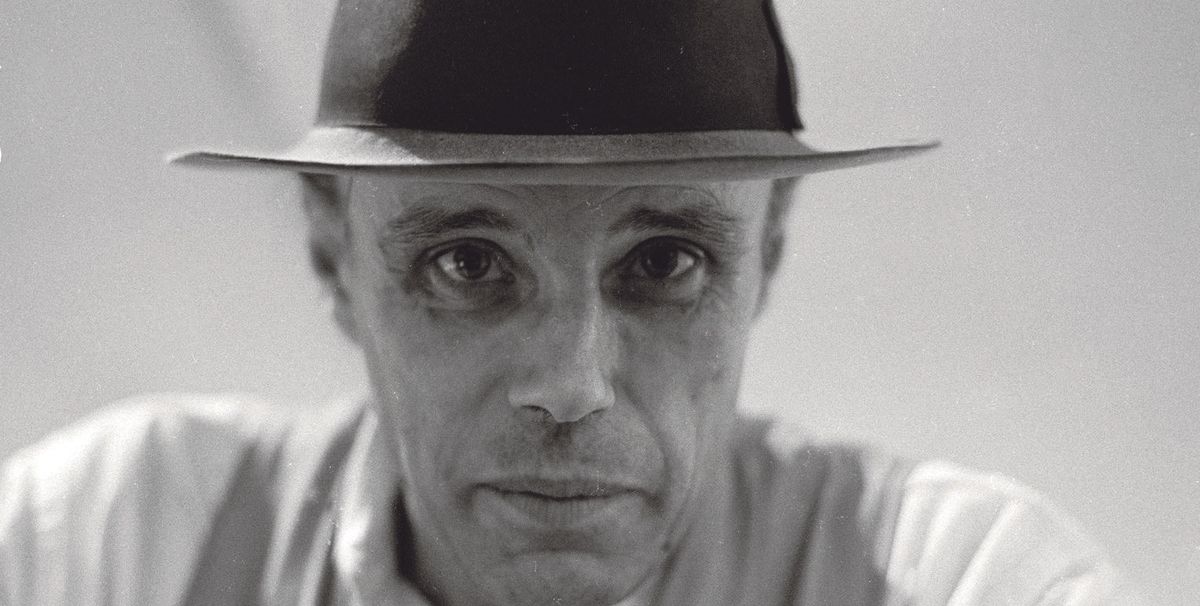

Marina Abramović performing Beuys’s 1965 work How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2005 Photo: Kathryn Carr; Courtesy of the Marina Abramović Archives

Marina Abramović is one of many contemporary artists who have paid tribute to Joseph Beuys—alongside Ai Weiwei, Olafur Eliasson, Christoph Schlingensief and Matthew Barney, to name just a handful.

In 2005, Abramović re-enacted his performance work How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. She said she wanted to remind a younger public of the “immensity” of Beuys’s work. “I think they are starting to forget,” she said. “But we can’t forget. Everything is going in cycles in art.”

Beuys, who would have turned 100 this year, is often mentioned in the same breath as Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol as a towering figure of the 20th century. His relic-like sculptures in felt, fat and wax are not as consumer-friendly and accessible as Warhol’s upbeat Marilyns and beans. But in our current era of social and environmental upheaval, Beuys’s ability to cross the borders between art and politics make him perhaps more relevant and exciting. Abramović’s “cycles of art” are rotating Beuys back into the foreground.

Beuys not only posed the question of what art is for, but also put the question of democracy at the core

The 100th birthday celebrations “coincided with the intensification of the climate crisis and the pandemic, and the sense of having to rethink everything,” says Catherine Nichols, the co-curator of Beuys 2021, a programme of anniversary events at institutions in 14 cities in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia. “Beuys not only posed the questions of what art is for, what a museum is for, what educational institutions are for, but also put the question of democracy at the core.”

Beuys was a founder member of Germany’s Green Party, and therefore a pioneer of the global movement to protect the environment.

“His work is influential beyond the art world in the sense that it transgressed the limits to politics, and that is clearly different from Duchamp or Warhol, who never questioned these limits,” says Philip Ursprung, whose book Joseph Beuys: Kunst Kapital Revolution was published this year.

Greta Thunberg protests against climate change in Stockholm in 2018 Photo: Jasper Chamber/Alamy Stock Photo

So it follows that any examination of his legacy should extend beyond the realm of art—in keeping with Beuys’s famous observation that “everyone is an artist”. That is the title of a recent anniversary exhibition at the K20 in Düsseldorf, which drew parallels between Beuys and Greta Thunberg, who used her passion and charisma to spark a global protest movement. In the catalogue, Eugen Blume likens both to shamans who overcame shattering personal crises to find a sick world that they seek to heal—by provoking those in power and mobilising the masses.

In 2019, Thunberg arrived in New York by yacht to challenge the UN with her “How dare you?” speech. In 1974, Beuys took an ambulance from the airport to a New York gallery to spend three days with a coyote in his performance work I Like America and America Likes Me. His intention was to shine a spotlight on the oppression of indigenous peoples in the US.

In the art world, the extent of Beuys’s legacy is vast—not least because he won new audiences. “It was a moment when contemporary art started to move from a niche to centre stage,” Ursprung says. “[German news magazine] Der Spiegel put Beuys on the cover, and people started to flock into the museums, especially in West Germany. Contemporary art became something that everyone cares about.”

His work remains somewhat messy; we cannot bring it into an order as we would like to

And yet perhaps this legacy is not yet fully understood. Beuys scholarship so far, Nichols says, has often been “nebulous”, in part because of the cult-like following he inspired. “Very little of it has critical distance,” she says. “It tends to be passionately anti-Beuys or passionately pro-Beuys. In a way that is exciting because it means there is a lot still to be done.”

His political position, too, is ambivalent, Ursprung says. Much of the debate about Beuys during his centenary year has focused on his connections to former Nazis (in 1976, before the founding of the Green Party, Beuys stood for parliament in a right-wing party founded by a former Nazi.)

“Perhaps it is this ambivalence and the many ideological threads woven through the work that continue to make it exciting,” Ursprung says. “It remains somewhat messy; we cannot bring it into an order as we would like to.”

It is probably Beuys’s concept of the “social sculpture” that is most influential in our era; the idea that all life can be viewed as art. Ursprung cites Thomas Hirschhorn as a clear successor to Beuys as “an artist who wants to use art for social change, in terms of offering a space where something can happen, and in the sense of being available and accessible personally in an exhibition.”

Hirschhorn’s 2019 monument to Robert Walser, for instance, located by the railway station in Biel, Switzerland, was an open invitation to the local population to exchange views about the writer’s life. Made of chipboard, pallets and sticky tape, it included a kindergarten, a library, a television studio and a canteen.

Beuys’s legacy is inextricably linked to Documenta, the contemporary art exhibition that takes place every five years. His 7,000 Oaks project, a “monument to the treatment of nature” to protest against town planning that prioritised cars, consisted of planting 7,000 trees—each accompanied by a basalt stone from a pile dumped on Friedrichsplatz in Kassel in 1982. The heap of stones in a public place was deeply unpopular, but it also forced action and mobilised the whole city to get the work completed.

Ai Weiwei’s Template at Documenta 2007 echoed Beuys’s work. The sculpture of centuries-old Chinese doors removed from houses, a criticism of the neglect of heritage and history in his homeland, also ended up in a messy heap after a storm. For that same Documenta, in a “social sculpture” with far-reaching repercussions that caused a political stir, Ai invited 1,001 Chinese people to Kassel.

He referenced Beuys directly at the K20 in Dusseldorf, the city most associated with Beuys. In 1972, Beuys produced a poster of himself striding purposefully towards the viewer, with the slogan “We Are the Revolution”. A poster of Ai leaning back in a waiting pose at the 2019 exhibition asked: “Where is the revolution?”.

Beuys’s influence is immediately visible in the work of activist environmentalist artists such as Olafur Eliasson, whose Ice Watch featured melting blocks of glacier ice on a square in front of the building where the UN climate talks were taking place. Earlier this year, Eliasson flooded the Fondation Beyeler with bright green water for the exhibition Life, bringing the environment into the museum.

To make a different political point in a “social sculpture”, the artist Suzanne Lacy explored the border between Northern Ireland and Ireland during Brexit with 300 participants. Phyllida Barlow, Theaster Gates and Schlingensief are other artists who have taken the concept to new levels.

The next Documenta, in 2022, also promises to develop Beuys’s ideas of art as democracy, collective engagement and activism for the modern era. Ruangrupa, the Indonesian collective curating the exhibition, has only invited other cooperatives with social objectives to participate, such as the Wajukuu Art Project operating in the slums of Nairobi and the Palestinian organisation Question of Funding.

Beuys would probably approve. He was an artist who “really put his fingers into all the wounds at that time in society”, Nichols says. In an interview with the German Tagesspiegel newspaper, Ruangrupa member Reza Afisina said he was particularly interested in Beuys’s performances. “They were very anti-establishment, and that connects us to his work,” Afisina said.

• Art Basel Conversation, 100 Years of Beuys with Philip Ursprung, professor of history of art and architecture, ETH Zürich, and Catherine Nichols, curator and co-chair of Beuys 2021, 25 September, 5pm-6pm