The Chinese artist Ai Weiwei is not particularly optimistic about the right to freedom of expression for artists and writers around the world. Nor does he think the art world is helping much. But Ai seems happy to keep up the fight ahead of the unveiling of a new work commissioned by the human rights organisation English Pen, which will be unveiled at London’s Southbank Centre tomorrow for the English Pen 100 festival of talks by renowned writers covering topics such as freedom of speech and writing in exile.

Speaking from his home in the Portuguese countryside, where the artist has spent most of the pandemic, Ai spoke about the need to protect artists' ability to speak freely, the growing repression in Hong Kong, and how imprisonment in 2011 inspired him to begin writing his forthcoming memoir.

A still from Ai Weiwei's new film being projected at the Southbank Centre

The Art Newspaper: Can you tell us about the work you are making for the Southbank?

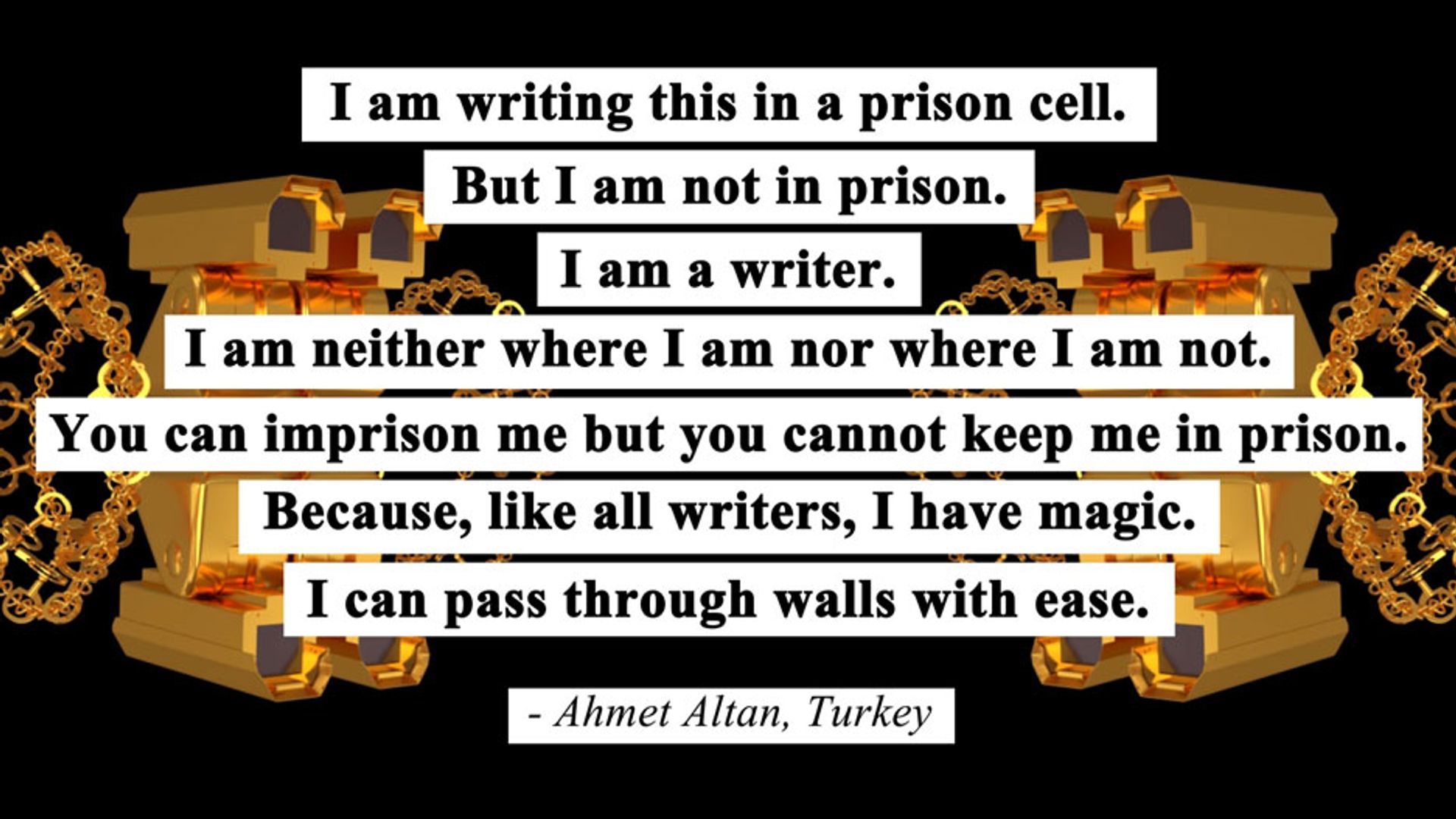

Ai Weiwei: We are presenting a group of works from different writers mostly rooted in Britain. It has a clear intention to focus on the idea of freedom of expression through historically renowned writers.

You are a big proponent of freedom of expression. You have said in the past that autocratic governments fear art and freedom of expression. Can you tell us more?

When a society is dominated by one idea or one belief, then the restriction on freedom of expression is always there. [It] is not only communist or authoritarian states. It happens everywhere as long as there is a single ideology or religion that dominates. To block, censor or erase different voices is a very efficient tool to control [people].

Do you think that it has got worse? For example, with the implementation of the national security law in Hong Kong last year.

For Hong Kong this is a totally new condition that will completely change its political temperature. You will have no freedom of expression at all—in every aspect—from newspapers, media, even museums, or whatever. Even in schools, from Kindergarten they start this forced brainwashing of the people in Hong Kong.

You mention museums being affected. There has been some controversy around M+ museum in Hong Kong planning to not exhibit a photograph you made giving the middle finger in Tiananmen Square and removing it from their website. Do you think they will ever show that kind of work?

I don’t think so. I think M+ museum is under municipal control, and the municipal is part of the Chinese government. There is no illusion about it.

“There is no difference [between Christie’s and] a French market selling perfumes”Ai Weiwei

What do you think about the recent announcement by Christie’s auction house that it is opening a new headquarters in Hong Kong suppressed

First, Christie’s is never part of the creativity but rather a pure market. There is no difference [between it and] a French market selling perfumes or XO selling brandy or all kinds of luxury goods. It’s not only Christie’s. Even museums like the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Centre Pompidou are trying to open their museums in Shanghai or Beijing, trying to squeeze in, because China continues to be the biggest market. The whole idea of those businesses is not about art but about the market. The [museums] lend their work to get some rent, one or two million annually, because the French are super poor. But they are still kind of selling perfumes.

What can the art world do in support of artists in Hong Kong who are being oppressed?

I wonder first if there is an ‘art world’? Or can ‘art world’ be replaced by some kind of business, [or] some kind of stock. The ‘art world’ has long [been] far from what the meaning of art should be—artists should relate to the human struggle and the wellbeing of our state of mind. I think the ‘art world’ doesn’t really exist.

How about artists who campaign for freedom of expression, can they make a difference in places like Hong Kong?

I think if anybody wants to do it, it won’t make a difference. After all, art should affect our human soul and should benefit individuals. As artists, we are individuals, and first we should benefit ourselves—we have to have the freedom of expression as a fundamental value. Otherwise, I [can’t] even understand what you can really express [without freedom].

A still from Ai Weiwei's new film

In the past you have signed letters in support of various causes and attended protests. Do you think the art world—if there is such a thing—can help by organising campaigns?

I think art is about human difficulties. Signing or sending letters is the minimum you can do. But it doesn’t really work that well because authoritarians crush freedom of speech without [allowing] any space for negotiation. I would say art itself is subversive. And it should be done [in a way that] destroys the old structure. Spiritually, it has to be violent. Not physically violent, don’t get them mixed. Without this subversive power, art will just be a loser, it’s not going to fight effectively with those powers. [They] are ultra-powerful, they dominate every aspect of our lives, [pushing] human society to a very dangerous stage. We can see environmental problems, political corruption, ideology lost, we can see in every aspect we are losing ground. An artist should be someone who has a clear vision and has a clear responsibility. And should have some skill to make the expression effectively, to be heard.

Do you think it is difficult for artists to effect changes through direct protesting, in cases like the treatment of Uyghurs by the Chinese government?

The artists in China cannot do anything. Even just [making] a joke can cost your life. It can make you almost not exist; your voice can never be heard. But artists in the West have this kind of illusion that they have freedom, or they have some kind of democracy to protect them. But they totally lost the ability to fight, because the system rewards artists who decorate this kind of society. It is like training animals: you give clear signals and rewards to people who decorate these kinds of bourgeoise ideas. And there is no clear criticism and argument. So after generations of this kind of practice, the universities, education, the whole system becomes very corrupted. I don’t think [artists] are still capable of defending human values.

“I hope there is a hidden army”Ai Weiwei

You have lived in Berlin and Cambridge before moving to Portugal. Did you find that kind of thinking across Europe?

I have to say yes. Unfortunately, the human mind’s development has never been so uniform like today. Even in the most difficult times, like before the Second World War and even the First World War, you still saw the avant-garde really make progress in human thinking. A lot of very brave artists and writers came out. They never wanted to be trendy, they never wanted to be accepted by the mainstream. They were visionaries and we have benefited [because of] those people. That is why we have to promote freedom of expression, because that is the final [way] to measure the quality of our mind. Without that, our immune system becomes weaker and weaker.

If artists in China are oppressed and Western artists are pleasing the bourgeoisie, is there any hope?

I think this will continue; it has started to rot but it’s not completely rotten. Once the situation gets really bad, maybe there’s a chance we’ll see some hope. Not now, it seems people are still not awakened to that.

Are there any artists or writers who you think are doing a good job?

There are individuals who are defending those essential values but very few. I don’t think I should name [them] as I will miss a few. But I believe I’m just one of them. I hope there is a hidden army.

“In detention you cannot write one word, because there are two soldiers standing 80cm in front of you”Ai Weiwei

You have a memoir, 1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows, coming out soon. Did you begin writing the memoir during your detention by the Chinese authorities in 2011?

I started to think [about writing] down something while I was detained. Because they told me I would sentenced [to] a decade. I have no other regrets, I have been through so much, and I’m pretty happy and satisfied with my life. But [my only regret would have been] to not reflect on my father’s—the previous generation’s—life. [Not doing so] would make me feel like I have a duty that was not achieved. I thought I would write it down for my son: an honest reflection on what has been happening in the past 100 years. So that concept came from my detention. Once I was released, I started to write.

You didn’t start writing it while you were detained?

In detention you cannot write one word, because there are two soldiers standing 80cm in front of you. You cannot even scratch your head. You have to report to them, to say, ‘I have to scratch my head’. They will [allow] you to start doing it. After that you say, ‘I have finished the scratching’, [and] they say, ‘put your hand back’. It’s a very interesting procedure. That’s how states [work]. You have to listen to the authorities to give you permission [to do what you want], otherwise you get punished. Society is also like that, you either get rewarded or punished. But very unfortunately all the people who love freedom of expression have been punished somehow.

• English PEN 100, Southbank Centre, London, 24-26 September