The Kunstmuseum Basel recently opened its ambitious Pissarro retrospective, the largest Swiss show on the artist for 60 years. Camille Pissarro: the Studio of Modernism takes a fresh view, which the co-curator Josef Helfenstein hopes will prove a surprise. “Pissarro’s place in 19th-century art is underestimated and deserves to be re-examined and reassessed,” he says.

This comprehensive exhibition comprises nearly 200 works, including more than 100 paintings. Helfenstein, the Kunstmuseum Basel director who has worked with co-curator Christophe Duvivier, is presenting Pissarro as the “hidden leader” of the Impressionists, although he is now usually overshadowed by Monet, Renoir and Degas. “Without Pissarro the Impressionist group would probably never have been formed in the way that it was,” he says. “He held the group together with his charisma and was the most curious and open-minded of them.”

Pissarro was an outsider. He was born in 1830 to Jewish parents on the Caribbean island of Saint Thomas, then a Danish colony. Helfenstein points out that Pissarro went to a school for Black children until he was 12. Schools for white children did not admit Jewish pupils, but because Pissarro’s parents’ marriage was illegitimate according to strict Jewish law, he was barred from the Jewish school. At the age of 25 he set off to Paris to take up art.

Partly because of his multicultural background, Pissarro was very aware of the unequal distribution of wealth and later became an anarchist in France. But unlike some extremists, he favoured a non-violent revolution.

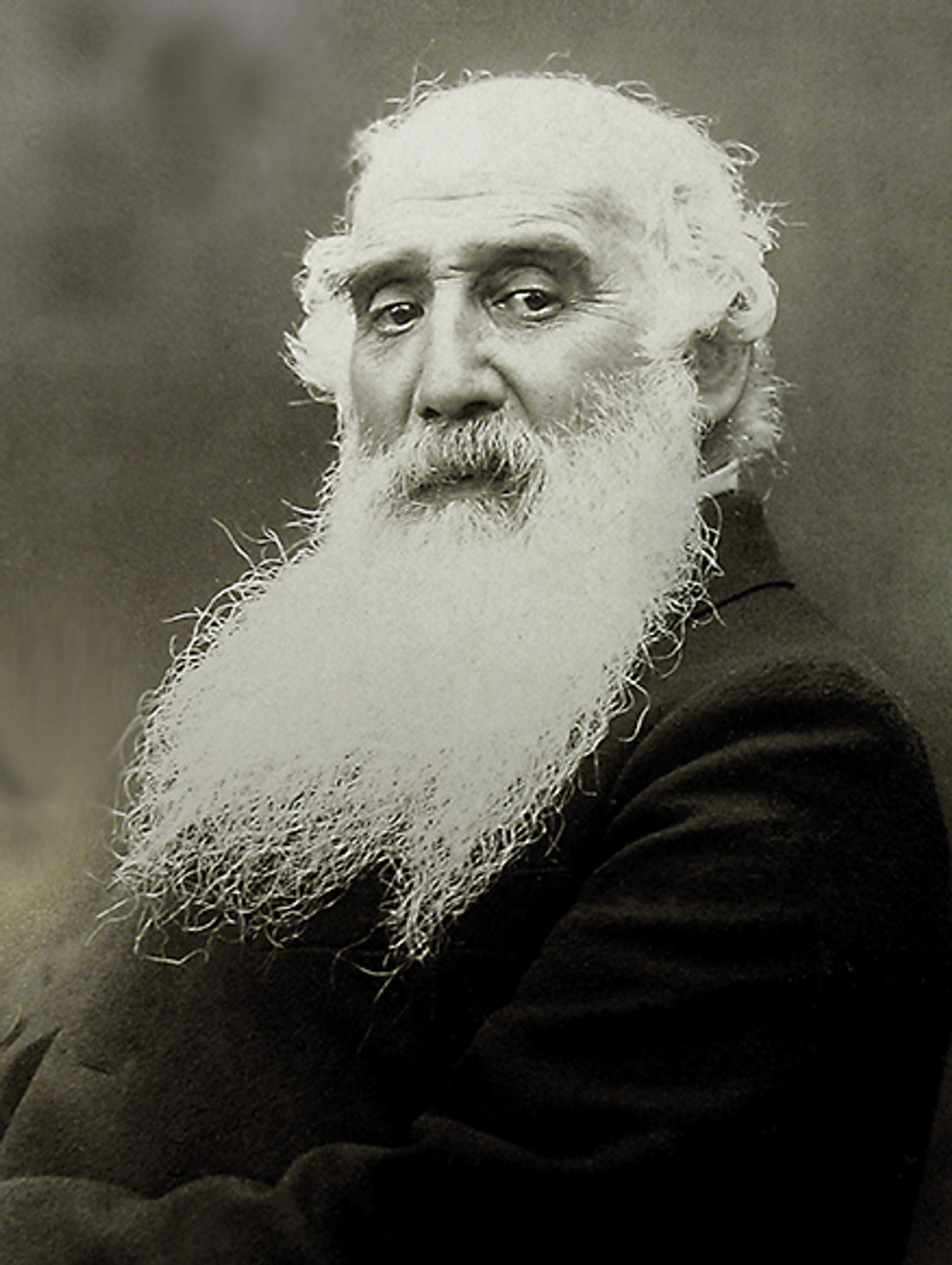

Camille Pissarro, photographed around 1900. The artist was born on the Caribbean island of Saint Thomas and moved to Paris at the age of 25 Photo: © Archives Musée Camille Pissarro

Among the surprises in the Kunstmuseum show is Turpitudes Sociales (1889-90), an album of ink sketches about the exploitation of workers in capitalist society. Pissarro drew this for his nieces Esther and Alice Isaacson, who were then living in London. It is now on loan from the Geneva-based drawings collector and retired banker Jean Bonna.

A highlight of the exhibition is the Kunstmuseum’s Neo-Impressionist painting Les Glaneuses (1889), which is presented alongside Pissarro’s preparatory gouache, lent by Florida’s Cummer Museum. Other works include four delightful fans, painted with landscape scenes. Londoners will enjoy seeing Hampton Court Green (1891), a cricket scene on loan from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Two self-portraits are very striking—one from 1873 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris) and the other painted 30 years later (Tate, London), just a few months before the artist’s death in 1903.

Eight of the pictures in the Kunstmuseum exhibition come from its own collection. In 1912, Un coin de l’Hermitage, Pontoise (1878) was the first Impressionist painting to be bought by any Swiss museum. La Maison Rondest, l’Hermitage, Pontoise (1875) is the latest acquisition, donated this year by the local Riehen collector Klaus Berlepsch.

Pissarro never achieved the financial success enjoyed by some of his Impressionist colleagues. This had a severe impact on his wife Julie, and the Kunstmuseum catalogue records that in 1887 she “came close to killing herself”. This little-noticed revelation comes from the art historian Joachim Pissarro, Julie’s great-grandson.

A key theme running through the exhibition is Pissarro’s influence on his colleagues. As Helfenstein explains: “His friendships with his fellow artists were remarkably intense and the selflessness with which he supported them was almost unique.”

Pissarro helped organise the first Impressionist exhibition in Paris in 1874 and encouraged the inclusion of Neo-Impressionists in the last show in 1886. His links with these artists are explored in the exhibition with works by Monet, Cézanne, Degas, Cassatt, Gauguin, Seurat and Signac.

A smaller version of this exhibition will travel to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, February to May 2022.

• Camille Pissarro: the Studio of Modernism, Kunstmuseum Basel, until 23 January 2022