Mikhail Piotrovsky grew up in the hallowed halls of St Petersburg’s State Hermitage Museum, the historic Winter Palace of the Russian tsars. His father Boris ran the museum for 26 years and Piotrovsky followed in his footsteps in 1992, taking the reins months after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Today, aged 76, he has served 29 years at the helm of the Hermitage.

“I came here when I learned how to walk,” Piotrovsky tells The Art Newspaper. “I loved to play on the Turkish drums. I went to children’s groups at the Hermitage. I remember one in the foyer of the theatre. I painted a gouache of Alexander Pushkin’s [1831 fairytale poem] Tsar Saltan.”

When he became an Arabist as an adult, Piotrovsky’s father engaged him as a tour guide for visiting dignitaries from the Middle East. “I showed Saddam Hussein around when he was still young.”

Today, Piotrovsky maintains close connections between the museum and the world of politics, enjoying the favour of President Vladimir Putin. He is even leading the St Petersburg ticket of United Russia, the pro-Putin ruling party, in national parliamentary elections scheduled for 19 September.

Piotrovosky says his decision was informed by the Hermitage’s role in the city and in Russian society. “I support the Petersburg line of Russian politics,” he says, distinguishing Putin and his team from the political clan of Dnepropetrovsk, the Ukrainian city, which ruled under Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev. “Being placed first on the ticket means the person has the highest confidence rating in the city. Where else in the world would you find a city where the director of a museum has the highest rating? It’s not because of me, it’s because of the Hermitage,” Piotrovsky says. “It’s not that I’m Putin’s person since the early 90s. Putin has been my person from the early 90s. He is from Petersburg. He had approximately the same job that I did. We both worked for the reputation of Petersburg. So indeed he is closer to me than many others.”

Piotrovsky operated on a similar principle in 2020 when he joined a working group helping Putin to draft sweeping constitutional amendments. He says he and other cultural figures made sure there are clauses obligating the government to support culture, which became especially useful when the Covid-19 pandemic devastated museum finances.

“When covid hit, we went to the government with this amendment and said we don’t have money, we don’t have visitors, we can’t earn anything,” he says. “We told them, ‘You have obligations,” to help museums pay salaries during covid lockdown. “We almost literally pointed at the constitution,” meaning “we are not asking, we are demanding.”

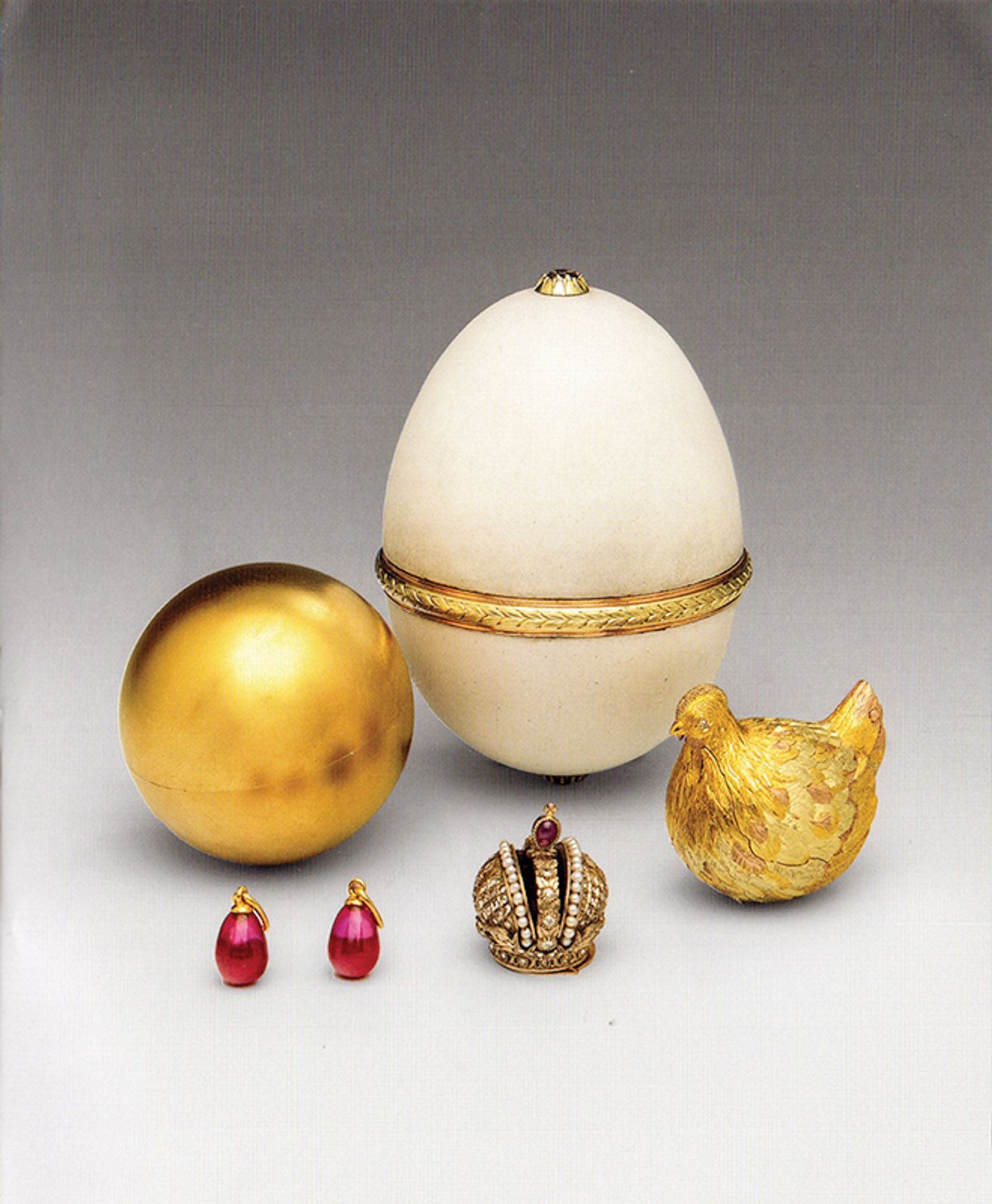

The Hen is among the Fabergé works on show at the Hermitage believed by Andre Ruzhnikov to be counterfeits

Those close ties to the president have also made Piotrovsky a target of investigative reports that claim he has over the years allowed friends to profit from an art transportation company and has sanctioned the presentation of fakes at the Hermitage, most recently of Fabergé objects on loan from an allegedly Kremlin-connected collector. Piotrovsky says the museum’s technical research has shown that rather than being faked, the pieces have had additions made to them over the years. “We have a plan to create a complete database of Faberge hallmarks,” he says. “Scandals need to be used to bring up certain topics for discussion, but in an intelligent fashion.”

As it opened to the world in the post-Soviet era, the museum relied on members of its own staff to supply souvenirs and transportation services, he says, “that brought income of no less than a million dollars a year to the Hermitage.” The museum had to fight off attempts at criminal infiltration in the 1990s and disentangle itself from offers of services by “international cowboys”, which were rampant at the time. “One of my main achievements was that I was able to do it without shooting,” he says. Charges of corruption are “a battle with the special services that is fought using different kinds of propaganda”, and is “part of my job description.”

“When the president of Finland was supposed to visit us [in the 1990s] Putin was head of [St. Petersburg’s] external relations committee,” and proposed using the Hermitage as a venue for their talks. “He’s come to the Hermitage with many [foreign dignitaries],” from Tony Blair to Xi Jinping. “He knows how to walk around the museum and speak with people with whom he’s conducting diplomatic negotiations. This is very important. It’s a sign of culture.” In April, he met with Piotrovsky at the Hermitage and presented the museum with a gold, silver and bronze liturgical set commissioned by Tsar Alexander II for his daughter’s chapel at Clarence House in London, where she lived with her husband, Queen Victoria’s son Prince Alfred.

The museum’s activities have coincided with Russia’s geopolitics, including expeditions to the ancient city of Palmyra when the Russian military was supporting Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s forces in the country.

Piotrovsky recalls a conversation he had with Putin about the Hermitage’s broad international activities, in which he asked Putin if he could refer to them as “cultural aggression”. Putin responded that “cultural offensive” would be a better description. Piotrovsky stresses that host cities must initiate a satellite and find funding.

A rendering of the proposed Hermitage Barcelona, designed by the architect Toyo Ito © Toyo Ito & Associates, Architects

The pandemic-induced funding problems at the Amsterdam outpost have been resolved, Piotrovsky says. “The Dutch government has started to count Hermitage Amsterdam as its own museum and included it in the programme for state assistance, so we are provided with everything for a year and a half,” he says. “It has been rebranded with a greater focus on historic ties to Petersburg. It shows how well our recipe works. It’s not like the Goethe Institute or the British Council. There is no Russian government presence.”

Issues are still being worked out for planned satellites in Barcelona and Saudi Arabia, but Abu Dhabi and Qatar are now also lining up as potential locations. China, he says, with which an agreement has been signed, “is slow” and “deciding whether the satellite will be virtual or not.” The Hermitage Rooms at Somerset House in London, which closed in 2007, “became political due to [Mikhail] Khodorkovsky and [Alexander] Litvinenko,” the jailed oligarch and poisoned former intelligence officer.

Covid, Piotrovsky says, has changed the world forever, and museums are at the forefront of a post-pandemic reality. “Recently we were explaining how we are living in the time of coronavirus and how we will live later,” he said. “Now it’s clear that there won’t be a later.” Timed visits and safety measures will be permanent and digital initiatives, such as the Hermitage’s Instagram and new TikTok account, have drawn a big audience.

“Every exhibition is a celebration,” he says of offline museum activity today. “It’s like medicine. You see people’s faces and joy that you wouldn’t have seen five years ago.” Recent highlights include a Louvre loan of Raphael’s La belle jardinière.

The Hermitage can also counteract the ethnic conflicts by telling the cultural stories of the Caucasus, of Muslim Dagestan and Azerbaijan, Christian Georgia and Armenia, through the museum’s extensive collections. “Museum life must be more orderly, we must scream less, crowd around less, make less noise, and think more about serious and everlasting things,” he says.

Piotrovsky’s son, Boris, was appointed deputy governor of St. Petersburg in charge of culture and sports earlier this year, but “doesn’t plan to be director of the Hermitage.” Piotrovsky himself has no retirement plans just yet. Although his current contract is up in 1.5 years, the museum’s charter allows for a president. “I don’t plan to leave completely,” he says.

Where will the Hermitage be in 40 years? “It will be in the 19th century,” he says. “In any case it will be the best museum in the world,” even as covid alters current plans. “We all used to plan ahead, now we don’t know what will happen tomorrow. But the Hermitage will go on.”