• Read more about the Art Fund Museum of the Year Award 2021 here

The Centre for Contemporary Art (CCA) Derry~Londonderry is a gallery for new art founded in 1992 near the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. It has a team of just four and only the director, Catherine Hemelryk, works full time. In lockdown, this small but talented group took advantage of their fleet-footedness to produce a raft of digital programmes and community resources reflecting CCA’s aims to create “opportunities for audiences to experience ambitious, experimental and engaging contemporary art, and for emerging artists to develop successful careers”, as the mission statement on their website puts it. “With everything that we did, we made sure that we came back to the question: ‘Are we fulfilling our mission?’,” Hemelryk says.

Entrance to CCA Derry © Marc Atkins/Art Fund 2021

Support for artists is fundamental. A dedicated programme known as CCA Supports immediately went online, offering artists 25-minute surgeries that act as “a sounding board and a different perspective”, she says. The platform was especially vital “because so many people were isolated and would miss out on those informal conversations that you’d have in a studio group, or down the pub, or in galleries with other humans”. A long-cherished idea for a “crit group”, where artists can share and discuss their work, was also realised during lockdown. “It has a lot of camaraderie because everybody wants the best for everybody else,” Hemelryk says. The crit sessions are set to continue after the pandemic—both online and in the gallery.

With the building closed for much of 2020, CCA commissioned artist takeovers of its social media channels. The brief “was really open”, Hemelryk says. Artists had access to the gallery’s Twitter and Instagram accounts for 24 hours and were paid a fee (CCA gave paid opportunities to a total of 65 artists over the past year). Some posted about their research interests, others used the space as a medium for new work, others to spread the word about their peers and influences. “Some of them made it extremely personal,” Hemelryk says, “which was really heartfelt, and those posts particularly connected with people”. The gallery also published roundtable podcasts and put works of art in its windows for the local community to enjoy on their daily lockdown walks.

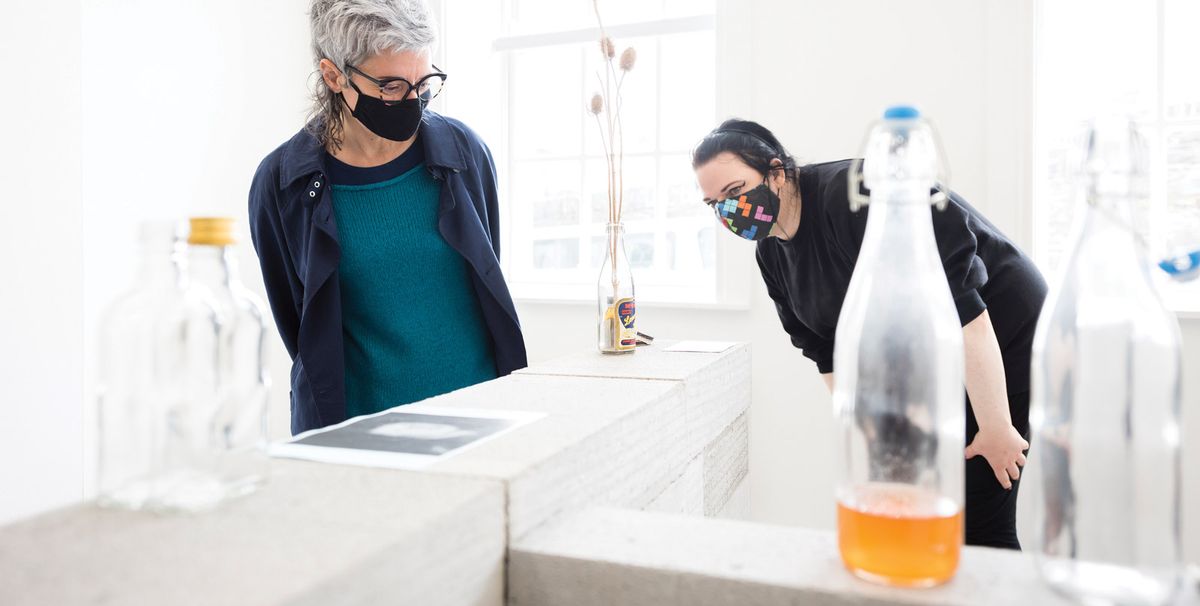

Visitors to CCA’s reopening exhibition Irish Modernisms © Marc Atkins/Art Fund 2021

A key part of CCA’s activities involves local schools. Before the pandemic, children “knew that they could come into CCA—it’s for them”, Hemelryk says, and primary school groups would work directly with artists. In lockdown, the learning programmes relied on home activity packs and videos, she says. Derry~Londonderry has “extremely high, multiple levels of deprivation”, so it was crucial not to make assumptions about children’s access to resources. Hemelryk explains that “every pack would have absolutely every single thing that you need, and then that means they’ve got that pair of scissors going forward, they’ve got a glue stick. And they can use those for other things.” As schools reopened, teachers could use the materials and videos to support art-making in the classroom.

Patrick Hickey’s Untitled (Back Study) (2019–20), featured in the Urgencies biennial, when work was shown in the windows of private homes as well as in public venues across the city © Patrick Hickey

Derry~Londonderry’s location a few miles from the border of Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland inevitably makes it a complex city politically. CCA works with artists on both sides of the border and much of the work it presents is informed by social issues, even if the gallery declares that it is “free from political affiliation”. Again, Hemelryk puts her communities first, “getting the temperature of what artists are doing and inviting the artists into particular contexts to work”. She adds: “We show work that is political, but it’s not party political. So that work might be looking at bodily autonomy, about gender, sexuality… There’s a lot of work about identity, but these things are cross-community. And a lot of the activism that happens is cross-community.”

The gallery has distinctive programming that engages with this local context, such as Urgencies, CCA’s biennial open-call group exhibition for emerging artists based in or connected to Northern Ireland. Participants are selected by Hemelryk with a Northern Irish artist—the twice Turner Prize-nominated Willie Doherty for the first edition in 2019, and locally based Locky Morris this year. The 2021 show was adapted to windows and public spaces across the city this spring, including closed theatres, a shopping centre and people’s homes.

CCA director Catherine Hemelryk © Marc Atkins/Art Fund 2021

Should it win Art Fund Museum of the Year, how would CCA spend the £100,000 award? “Financial stability would be so great,” Hemelryk says. “Even just being shortlisted, the fact that the shortlisting comes with a [£15,000] prize makes such a huge difference.” Winning would allow the gallery to continue its online programme alongside physical shows and events, and expand it further. “There are so many programmes that we really want to do, but we can’t unless I don’t want to sleep,” she jokes.

Fundamentally, the money would bring security. “Annual funding is a constant race,” Hemelryk explains. “This would mean that we could invest in longer term projects, at least for a while—the precarity would stop.”

Visitors to the Irish Modernisms exhibition

Must-see show at CCA Derry~Londonderry, according to its director, Catherine Hemelryk: Irish Modernisms exhibition

“The current exhibition [until 18 September] features five artists, both emerging and more established, from Northern Ireland, though Ben Weir works between the Netherlands and NI. All of their practices are influenced by the legacies of Modernism. Like many places, [Modernist architecture] has been rather maligned here over the years. But it is part of the everyday infrastructure. It hasn’t really been considered very much. So it’s a long-term interest I have, and I was delighted when I saw that there was this generation of artists who were influenced and it was playing through their practices. There are lots of overlaps through the show but each case is different. The title is Irish Modernisms because it isn’t just one homogenous thing.”

• Read about the other shortlisted museums here