With more than 1,000 stained-glass windows spread across 200 churches, the northeastern Aube department is France’s capital of the traditional craft. This rich heritage is why the local government moved in 2011 to establish the country’s first cultural venue dedicated to stained glass in the medieval town of Troyes. Before it opens in spring 2022, the Cité du Vitrail is holding a curtain-raiser on 18-19 September, the European Heritage Days, with preview tours of its newly restored home.

Known as the Hôtel-Dieu-le-Comte, the U-shaped former hospital is a listed historic monument of France, having been founded in the 12th century by Henri I, the count of Champagne. The building was purchased by the Aube department in 1990 and the east wing was later turned into a branch of the university of Reims.

The Hôtel-Dieu-le-Comte in Troyes © Cité du Vitrail - Sylvain Bordier

The Cité du Vitrail will occupy 3,000 sq. m in the west wing, including a chapel that has undergone an ambitious €1m restoration as part of the €15m overall budget—footed almost entirely by the department, with support from the town of Troyes and the Grand-Est region. It is a major step up from the trial programme of free stained-glass exhibitions run by the local authority in the Hôtel-Dieu-le-Comte’s former barn from 2013 to 2018.

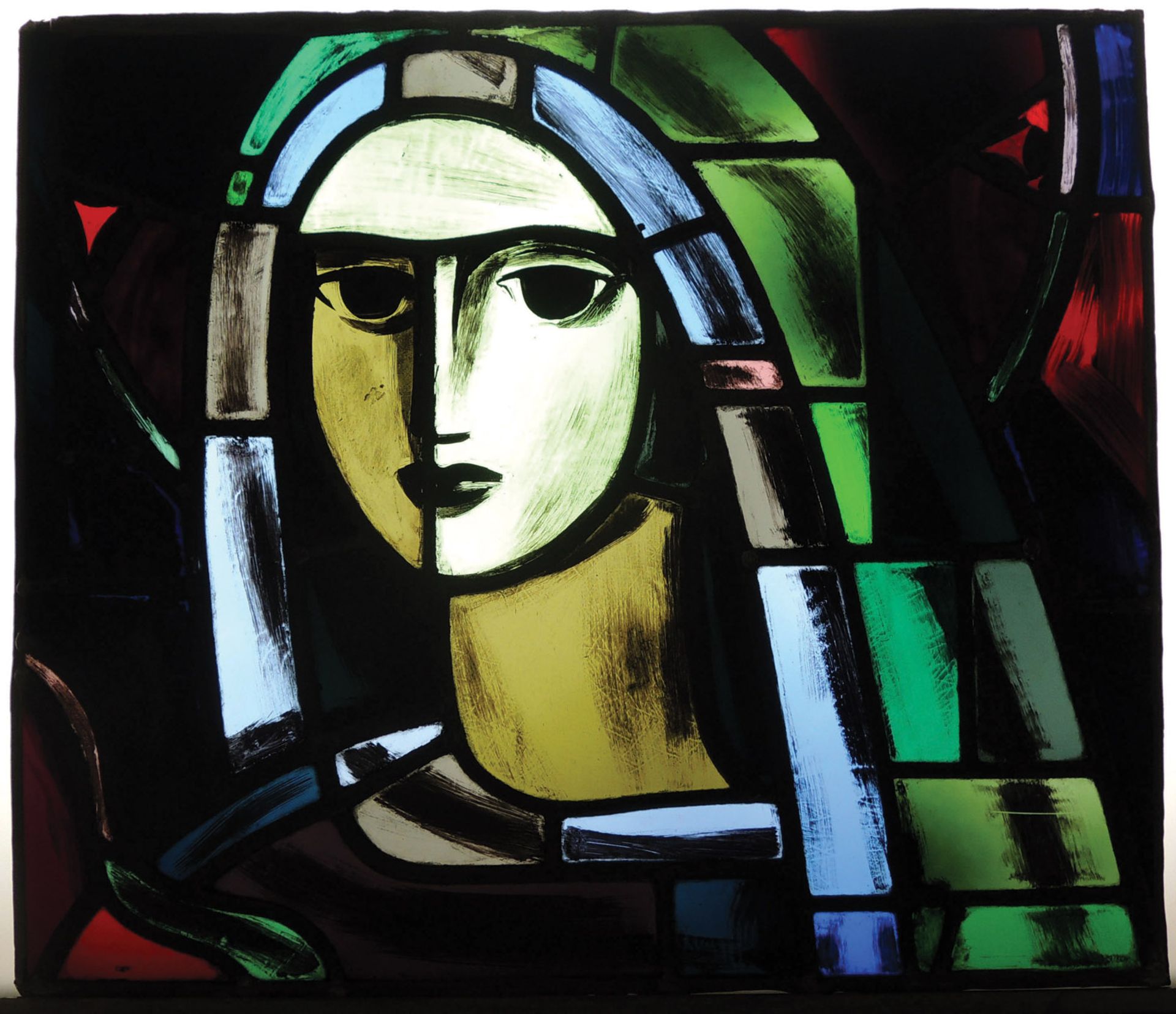

A detail from a 1937 stained-glass work by Jacques Le Chevallier © Cité du Vitrail

When works began, “the chapel was in worse shape than anticipated,” admits the heritage curator Anne-Claire Garbe. “Shreds of paint were falling off the ceiling. Part of the restoration took place ten metres above ground, sometimes upside down.” Specialists used sponges, cotton buds and seaweed adhesive to salvage the frescoes. The diamond-shaped glass windows from the Second World War were replaced by triple-glazed square panes for better insulation. Art historians are still studying whether the angels on the ceiling and the trompe l’œil figures on the walls are by the same artist.

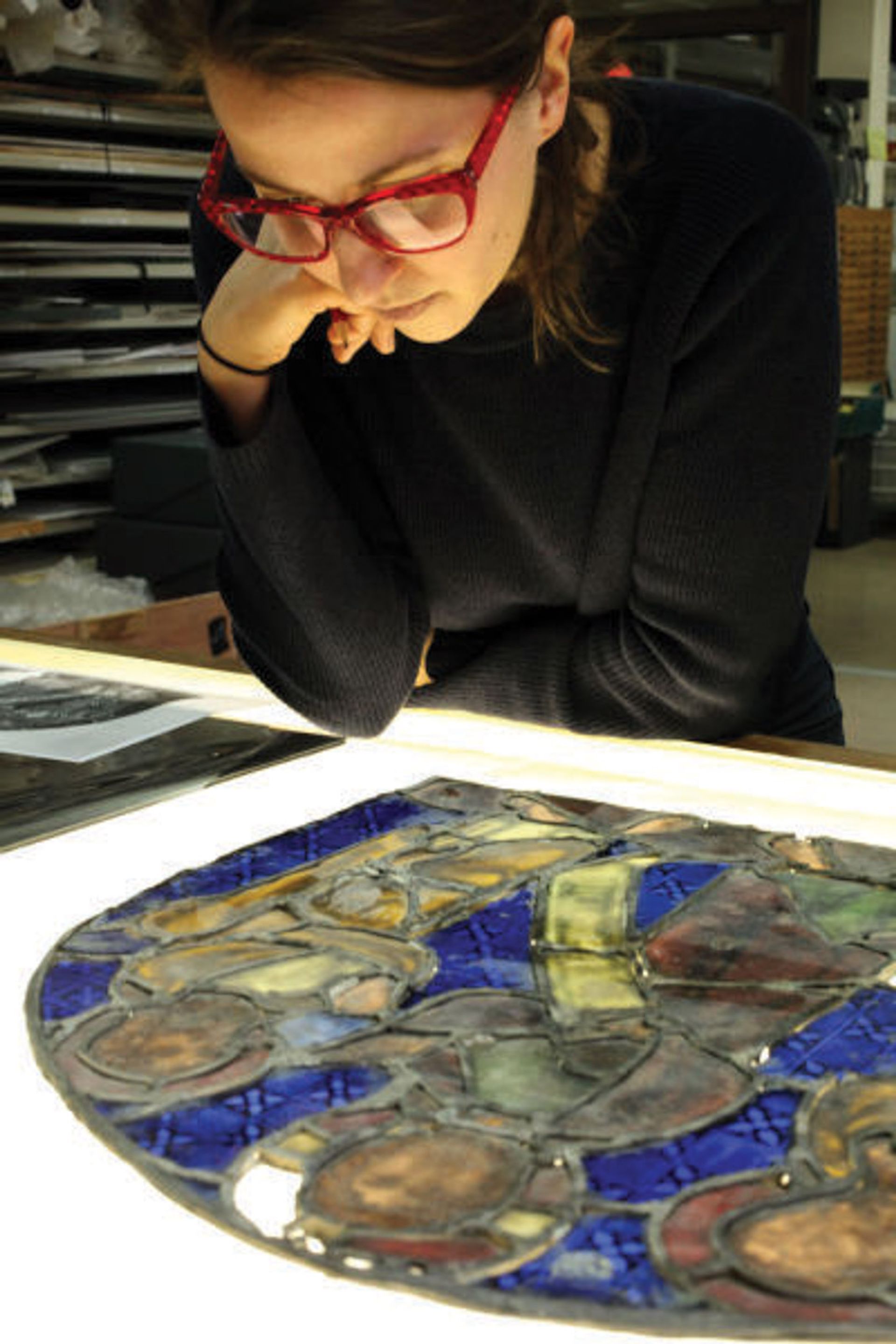

The Cité du Vitrail will house a research centre for stained glass © Cité du Vitrail

It took six months to restore the oak staircase, raising the bannister and reinforcing the steps. Along with a brand-new lift, it will provide public access to all six levels.

Outside, on the south-western façade, an 11m sundial attributed to the 18th-century designer Jean-Baptiste Ludot had to be re-engraved and its slightly dislocated metallic structure reinstalled so the sun would hit at the perfect angle for passers-by below to tell the time. The whole process was supervised by a gnomonics specialist, Jérôme Bonnin.

The collection includes a fragment of stained glass from the Atelier Simon-Marq in Reims © Cité du Vitrail

In the lower chapel—soon to become a research centre—a hatch in the wall for abandoned babies came to light in 2018. “We knew it was here but it was poorly documented,” Garbe says. “We thought it had disappeared when in fact it was concealed behind an insulation board.” An inscription with the letters “ENFA”—part of “enfant” (child)—was still visible on the façade.

The idea for the research facility was inspired by a stained-glass library amassed by the art historian Christiane Wild-Bloch, which her husband donated to the Aube department. The main reading room will be filled with interactive devices for all to enjoy, while a back room of records will only be accessible by appointment.

The chapel of the Hôtel-Dieu-le-Comte after restoration © Archives départementales de l’Aube

The second floor will be devoted to temporary exhibitions, while the permanent displays will comprise 50 stained-glass windows as well as glass fragments, paintings, sculptures and works on paper drawn from the collection of 750 pieces currently stored in the Aube department’s archives.

The oldest and smallest object on view next spring will be a seventh-century 3cm fragment borrowed from Rouen’s antiquities museum. The largest work, a long-term loan from the Cité de l’Architecture in Paris, will be a window presented by Louis Steinheil, Charles Leprévost and Albert-Louis Bonnot at the 1878 Paris World’s Fair. The most recent, meanwhile, is being designed by the artist Fabienne Verdier in collaboration with the local stained-glass workshop Manufacture Vincent-Petit. It should be ready for the chapel’s oculus just in time for visitors to arrive this month.