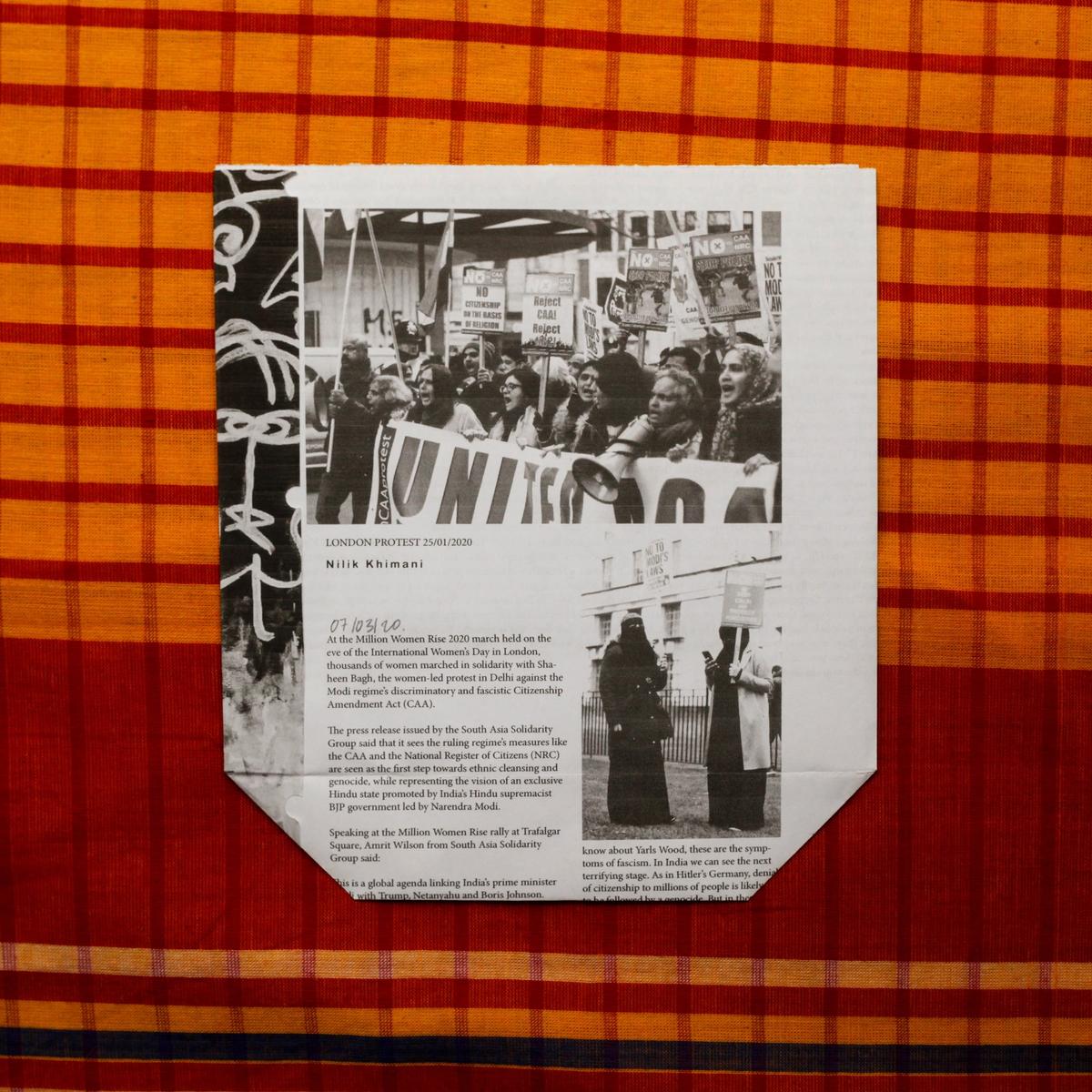

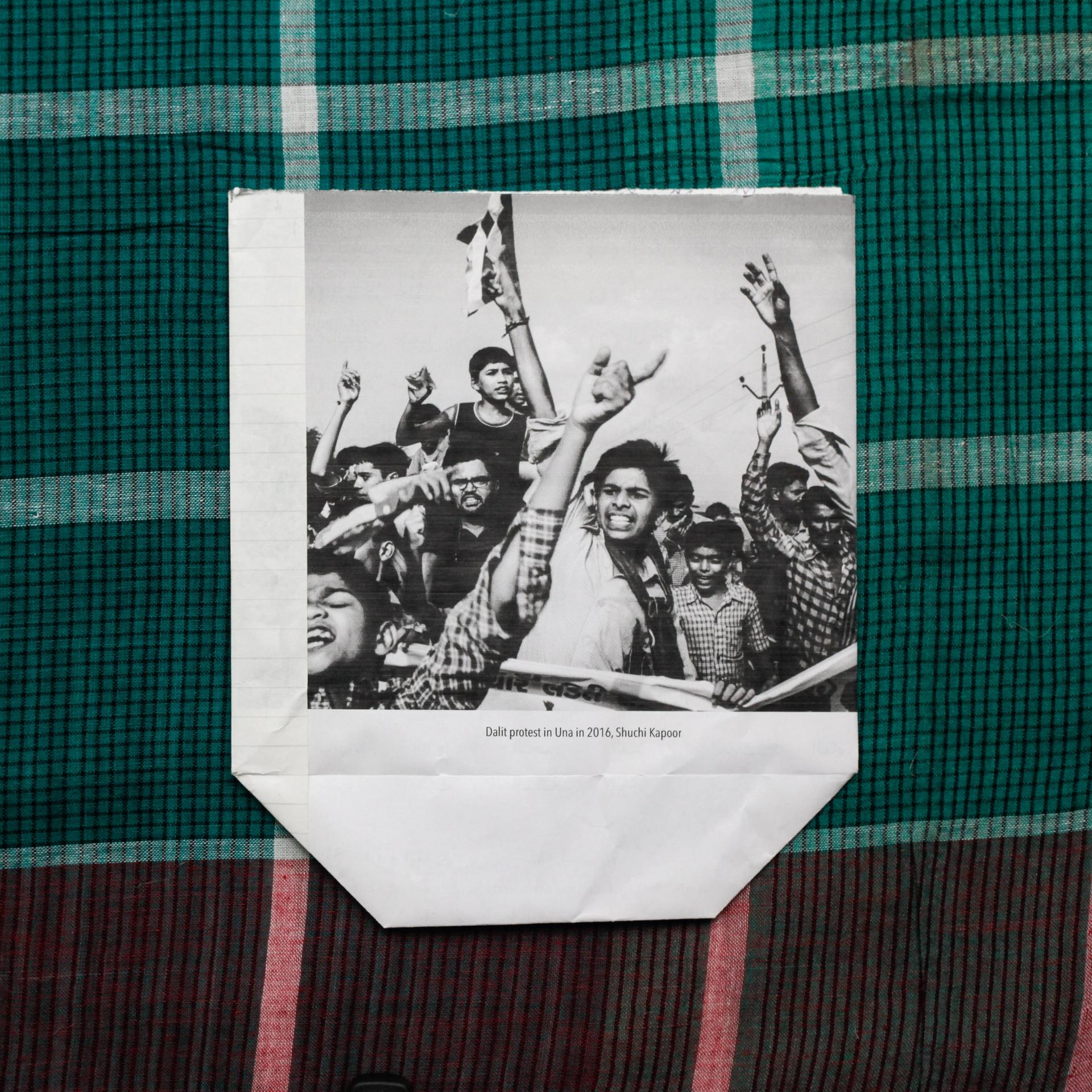

An unassuming series of paper samosa packets is among the nominees for this year's Jameel Prize, an annual award organised between the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (V&A) and Art Jameel that honours contemporary art and design inspired by the Islamic tradition. Emblazoned with images of protests from across the Indian subcontinent, as well as poems and messages of resistance, they form Turbine Bagh, a collaborative artist project devised by the London-based architect, artist and human-rights activist Sofia Karim, which rallies against fascism in India and Bangladesh.

Turbine Bagh takes its name from two sites of great political significance to Karim. Bagh, meaning garden in Urdu, refers to the neighbourhood Shaheen Bagh in Delhi, where a mass protest took place in 2019 and early 2020 against new citizenship laws widely perceived to discriminate against Muslim and other minority populations in India. Karim's project was initially conceived as a sit-in solidarity protest in the Tate Modern's Turbine Hall in April 2020, then home to Kara Walker's monumental, anti-colonialist sculpture Fons Americanus (2019), but the demonstration was cancelled due to Covid-19.

Forced online, the project's scope quickly evolved after the Bangladeshi photojournalist Kajol disappeared from his home, prompting Karim to launch a campaign on Turbine Bagh's Instagram to pressure the Bangladeshi government and find Kajol. Efforts were successful, and Kajol turned up alive after 53 days. Since then, Turbine Bagh has grown a digital platform that advocates for the freedom of political prisoners in South Asia and raises awareness of human rights injustices across the world. And while it still focuses mainly on issues in the subcontinent, such as the Dalit Rights struggle and artist censorship in Bangladesh, its remit has expanded to include movements such as Black Lives Matter.

Wedding art and activism is a longstanding tradition in Karim’s family: her maternal uncle is the well known Bangladeshi photographer Shahidul Alam, who in 2018 was abducted and imprisoned by the Bangladeshi government for 102 days after he publicly criticised its handling of a student protest. A year-and-a-half in, the project continues to gain traction and its efforts have been shared by the likes of the artist Anish Kapoor and the actor Sharon Stone.

Sofia Karim Photo: David Gonzalez

The Art Newspaper: Turbine Bagh has evolved considerably in scope since you began the project in March 2020. How did lockdown affect this?

Sofia Karim: Once mass events were banned we had to rethink how we could stage an international protest. We decided to use a digital human chain, with individuals posting photos holding a sign saying: "Where is Kajol?". Although the protests had shut down in India, arrests continued in both in India and Bangladesh. And so Turbine Bagh quickly pivoted into digitally campaigning for political prisoners. 18 months later, the samosa packets are still there but the project has effectively become a platform for political art, mainly from India and Bangladesh, but also with contributors worldwide. At its core, however, Turbine Bagh has always been a portrait of collective struggle. And it is a way of holding on to beauty through the arts of our combined South Asian cultures, in the face of a regime which seeks to destroy all that is beautiful.

Why did you choose samosa packets ?

In February 2018 I bought a packet of samosa (‘shingara’ in Bangla) outside my uncle Shahidul Alam’s photo agency in Dhaka. The packet intrigued me. It was made from waste print-outs of lists of court cases: the state against citizens. Both in Bangladesh and India, there are of course thousands of such cases. I became obsessed with these packets, all made from waste paper. Some were kids' homework handouts with nationalist poems, some were news stories (often propaganda), and so on. A few months later when my uncle was jailed by the government of Bangladesh, I wondered if his court case would appear on a samosa packet. I began making my own packets to send to street vendors, to combat propaganda and tell the stories of our FreeShahidul campaign. That was how the idea of the samosa packet movement was born.

Practicality came into it too. This was a way to showcase collective protest art in the Turbine Hall in a cheap and beautiful way. I come from a culture that is inherently non-wasteful and I have never understood why the art world makes ‘sustainability’ so complicated. I’m not doing anything clever or creative. I’m just doing what my mum taught me. It also made sense for Turbine Bagh because food is such an important element to the Indian protests. (I’ve read that a common greeting at demonstrations is 'have you eaten yet?'). I'm interested in using an object ubiquitous across South Asia in a different way.

Samosa packet on Dalit protest in Una... Part of Sofia Karim’s Turbine Bagh project Photo: Sofia Karim

How do you create the packets?

I post call outs on Instagram for artists to email me their work and I combine their pieces with things that come to my mind in response: words, news clippings or speeches from marches happening here in London. I print the final work on old papers from my mum’s cupboards using her cheap printer. Then I photograph the object and share it on social media. My whole family is part of the process. My 83-year-old dad has no interest whatsoever in contemporary art, but haunted by these political events, he loves reading what’s on these packets and has come up with ideas of his own.

Shaheen Bagh and its solidarity protests were notable for being women-led, what other aspects of these movements have inspired your project?

Certain strands of Western feminism present South Asian women, particularly Muslim women, as comparatively ‘backward’—repressed, invisible and unable to act without the agency of our men. And yet we have the women of Shaheen Bagh—Muslim women are fighting to defend a secular constitution. There is no equivalent women's movement in the West that I can think of.

Shaheen Bagh is a collective struggle that spans across all classes and generations. These women are not traditional 'activists’, but are rather everyday women who have come out of their homes, to defend their country against the forces of fascism, to fight against citizenship laws and so much more.

Furthermore, it is not only the fact that they resist, but it is how they resist that warrants attention. At Shaheen Bagh, women managed to create a safe zone amidst the state violence. There were libraries, educational facilities, places for children to draw, and incredible works of art. Turbine Bagh seeks to highlight all things. Turbine Bagh also seeks to highlight the show of unity Indians have displayed, as this is something we should not forget: Muslims, Dalits, Adivasis, Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, Christians, Hindus, and others came together in a vibrant resistance movement.

You publicly criticise political parties such as the BJP [India's ruling political party]. Do you ever come under threat for your activism?

Because I'm based in the UK, I have the relative privilege of safety compared to many of the submitting artists, who are at the coalface. And we all know what the consequences of speaking out could be for them. But if they are prepared to take the risks that they take, then there is no excuse as to why me, or other diaspora people, should not also support the cause in some way, especially when international awareness is so crucial to this struggle.

Despite the large number of recent mass protests, incidents of human rights abuses in India and Bangladesh are, if anything, increasing. Why do you think this is?

We are now at a precipice. The world’s largest secular democracy has turned into a fascist, Hindu supremacist state with relative ease and I think that has largely been abetted by geopolitical support for India and Bangladesh. The way they are discussed is not the same as other repressive regimes. If one asks a man on the street what he thinks of China, Russia Iran, even Trump's America, he likely thinks repression. You say 'India', and people think of yoga, peace and vegetarianism— most of the people I speak to are not even aware of the situation on the ground. But our democratic political structures are being re-shaped and the abuse of power becoming normalised. And if we don’t like what is happening around us, we need to stand up like the women of Shaheen Bagh. Things are not going to get better by themselves. India is an example of fascism unchecked.

• Jameel Prize: Poetry to Politics, V&A London, 18 September-28 November