Phillip King was an explorer. Born of a French mother and an English father, he spent his early years in Tunisia, experiencing different places and cultures, and he continued to travel throughout his life. He was also an explorer as a sculptor: innovative, resourceful and restlessly searching out new materials with which to make sculpture.

Materials led interesting lives in King’s London studio and the list of those he used across his career makes fascinating reading. From fibreglass, acrylic and plastic in the 1960s, materials would go on to be cast and constructed, cut and joined, bent and stretched, and brought closely together and integrated in surprising ways. In the 1970s we find steel mesh combined with concrete; slate with wood, chain and cable. Ceramics followed, after his time in Japan, where he worked on a potter’s wheel. When discussing his lifelong passion for materials in the context of a display of his work at the Duveen Gallery at Tate Britain in 2014, he remarked with a twinkle in his eye: “I’m always fascinated by new materials and my latest love is fluorescent Perspex.”

The new sculpture he was single-handedly creating in his studio during the recent lockdowns has a boldness, energy and colour vibrancy that we have come to associate with him

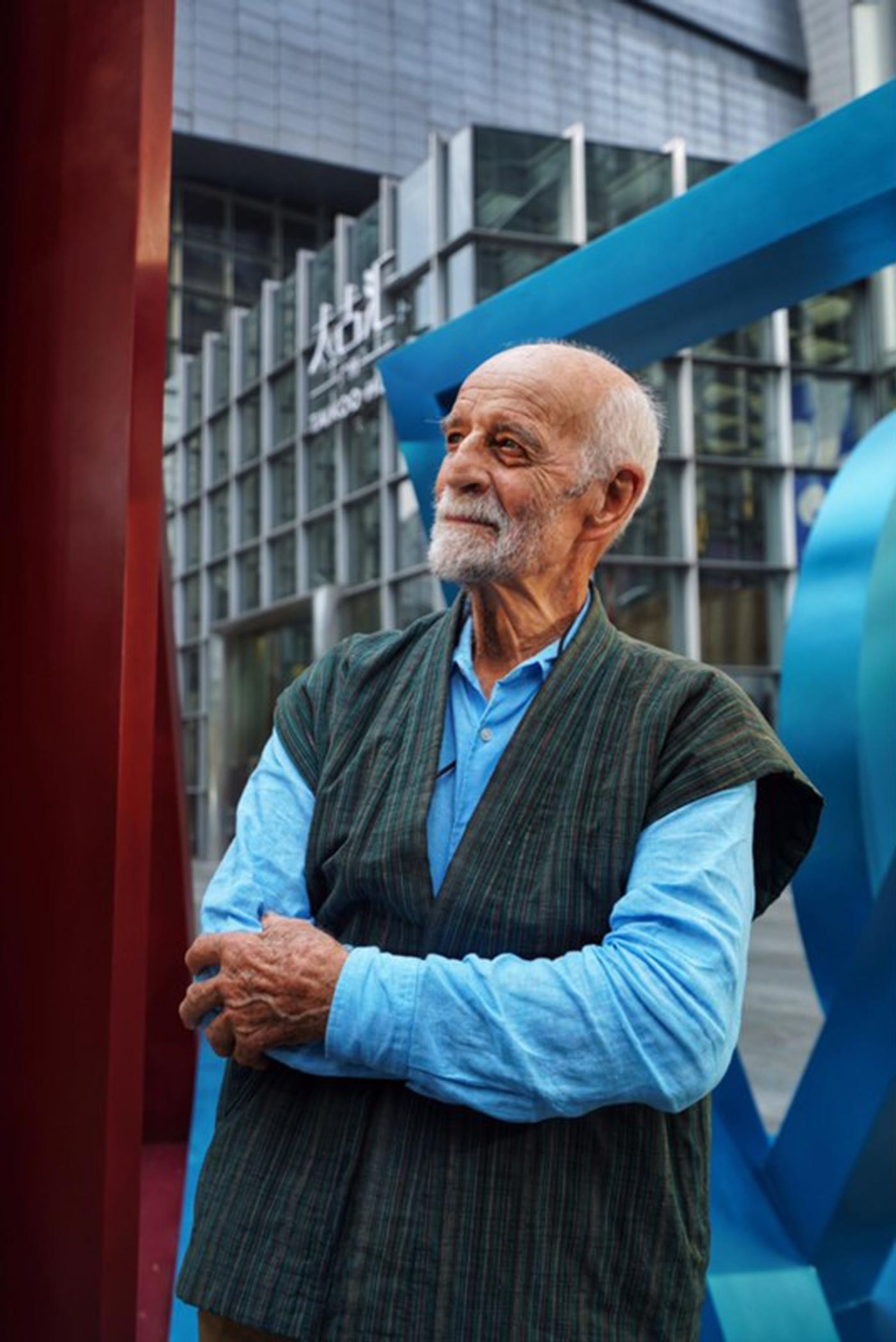

The Tate display, in part, was occasioned by his 80th birthday and King had been actively making sculpture since, working productively with Thomas Dane Gallery in London. The last decade saw shows in Switzerland, France, Norway and the US and he was looking ahead to forthcoming exhibitions, notably in Luxembourg. The new sculpture he was single-handedly creating in his studio during the recent lockdowns has a boldness, energy and colour vibrancy that we have come to associate with him. Loosely geometrical, asymmetrical blocks of blue, red, green, orange and yellow, poised dynamically and diagonally (as was often the way), are brought together as ensembles of interpenetrating forms. The colour of King’s sculpture today, as it was 60 years ago, is crucial. It was, in his own words, his “never-ending story”. The choice of paint was precise and well-trialled, and the light that activates it always well-understood.

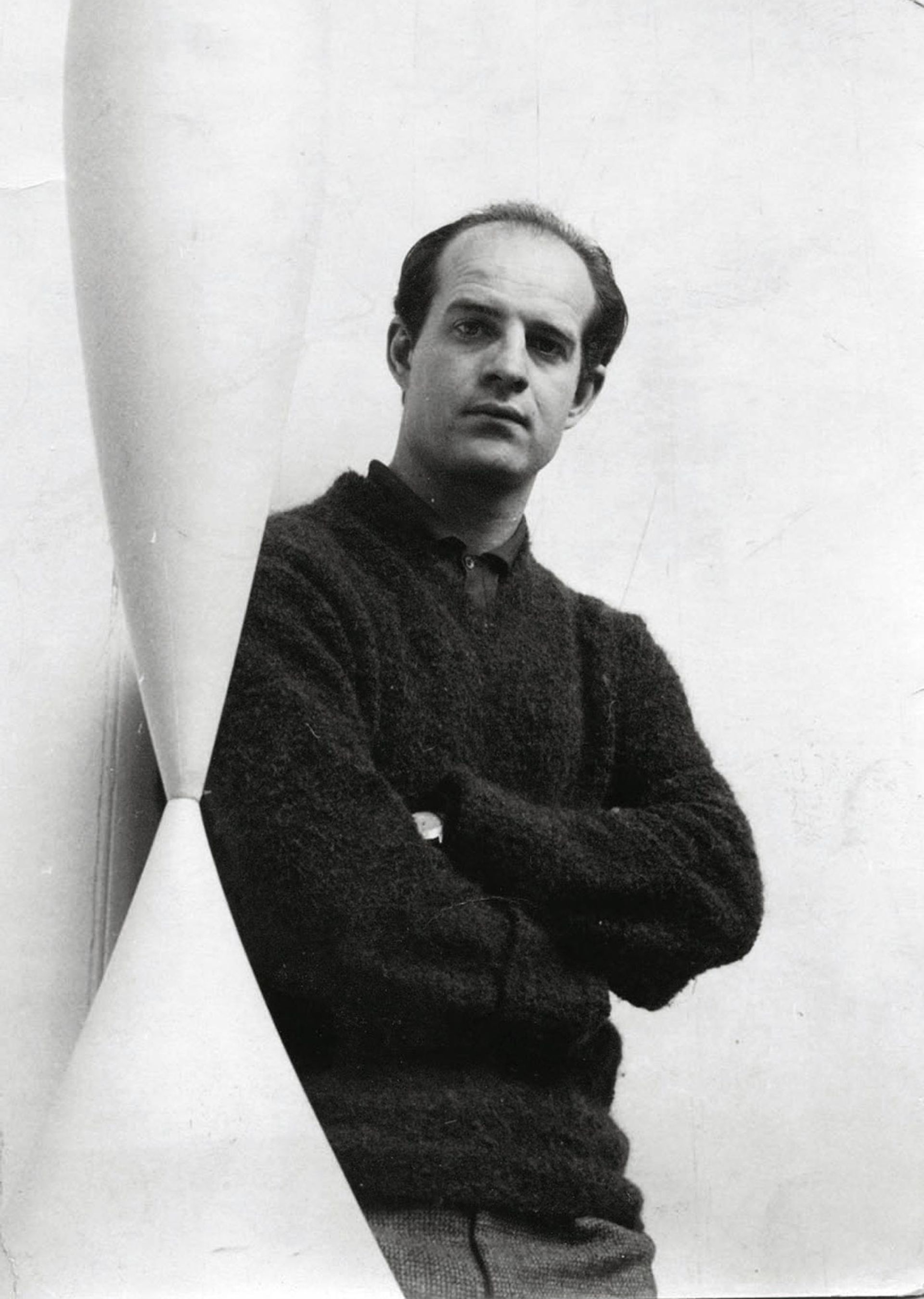

Phillip King photographed with his sculpture Tra La La, 1963 © Phillip King. Courtesy of Thomas Dane Gallery

King is well known to many as a sculptor who came to critical attention in the 1960s while working in the sculpture department at St Martin’s School of Art, alongside other artist-tutors there such as David Annesley, Michael Bolus, Anthony Caro, Tim Scott, William Tucker and Isaac Witkin. Though their works shared many qualities—and as a group became known as the New Generation sculptors—King’s own work was very different to Caro’s expanded multipartite welded sculpture, and it exhibited other ways of envisioning sculpture to his colleagues.

‘A familiarity that resists recognition’

King became known for his “cone” works, including Rosebud (1962), Twilight (1963), Tra la la (1963), Genghis Khan (1963), And the Birds Began to Sing (1964) and Through (1965). These extraordinary sculptures, equipped too with compelling titles, marked an important shift in sensibility away from the anxious figurative sculpture that had preoccupied so many sculptors in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War. King was younger (indeed ten years younger than Caro) and had an eye and mind not only for the work of Brancusi, but also for American painting and sculpture of the time, teaching at Bennington College, Vermont, in 1964. King’s “cones” works came out of this time, made from what he called “the inside out”—as opposed to “from the outside in”—an approach that carries with it powerful emotional and psychological meaning as well as sculptural logic.

Phillip King had the most original mind of anyone I have ever met. He also—and in consequence—made some of the most original sculpture of the 20th century.William Tucker

King’s ruminative approach to sculpture making —at once hands-on and poetic—was much appreciated by fellow tutors and students alike. William Tucker recently reflected: “Phillip King had the most original mind of anyone I have ever met. He also—and in consequence—made some of the most original sculpture of the 20th century.” He also recalls a time in 1960, before King had made abstract works such as Declaration (1961), when King was discussing what he saw as objects with an uncertain relation to objects in the “real” world. Tucker remembers: “Phillip had seen an informal show of welded steel pieces I had put together in a small exhibition space on the third floor and was intrigued. We started a conversation that was to go on intensely at first, and then at increasing intervals over the next 50 or 60 years. The immediate question was, what were these things I had made?... Phillip came up with a marvellous phrase to describe what I was after—an object with ‘a familiarity that resists recognition’, which has echoed in my mind ever since.”

Phillip King's Quill (1971) in Rotterdam, the Netherlands Photo: Wikifrits

The artist Jeff Lowe, who was one of King’s students at St Martin’s in the early 1970s, recalls him as both inquisitive and open-minded: “His constant questioning and curiosity was infectious. His teaching was never about ego, but from a genuine interest in understanding and developing what we were all trying to do as individuals and artists.” King taught at St Martin’s from 1959 to 1980 and had a short spell at the Hochschule der Künste in Berlin (1979-80) and then two professorships in London: the first (Emeritus) at the Royal College of Art in London (1980-90) and the other at the Royal Academy Schools (1990-99). This was then followed by five years as President of the Royal Academy (1999-2004), stepping down at the age of 70.

After heightened recognition in the late 1960s—representing Britain at the Venice Biennale (with Bridget Riley) in 1968 and with a large exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in London that year too—the 1970s brought what would be an ongoing engagement with sculpture in the open air and the relationship between landscape and sculpture. This extended his earlier considerations of the intimate, complex relationships between architecture and the natural world. His own work was being placed outdoors, beyond the gallery, and the Reel series, which he began in the late 1960s, remain some of the most remarkable sculptures he made. Reflecting on Reel (1969) in a lecture in 1998 he said: “A ‘reel’ is a traditional Scottish dance where one dancer follows another dancer. They join then separate… One could say that the act of standing up is a major preoccupation in all my work. Once stood up, it has to be steady, but free.”

A link with something greater

His interest in the ways sculpture could be freestanding, but might also be seen to enjoy a subtle connection to the spaces and places in which it was sited intrigued him and in 1972 he took part in the ambitious City Sculpture Project, working as a juror alongside Stewart Mason and Jeremy Rees, to have new sculpture installed temporarily across eight cities in Britain. King became a founding trustee of the Yorkshire Sculpture Park in 1977 and showed his own sculpture outdoors all over the world, including at the Kröller-Muller museum in the Netherlands in 1974 and Forte di Belvedere, Florence, in 1997. Most recently, he oversaw the installation of his large sculpture Free to Frolic at the Kistefos Sculpture Park in Norway in 2015, where sculptures by Lynda Benglis, Tony Cragg, Olafur Eliasson, Anish Kapoor and Claes Oldenburg are also shown, while his Darwin sculpture was placed in a square in Guangzhou in China in 2019. He was also in the process of making an ambitious new, large-scale work called La Ronde de Rennes, to be installed in the French city of Rennes. These recent acquisitions are the latest in a long and successful history of his work entering significant public and private collections, nationally and internationally.

Phillip King photographed in Guangzhou with his sculpture Darwin, 2019 © Phillip King. Courtesy of Thomas Dane Gallery. Photograph: Judy Corbalis King

Bilingual since childhood, King had a background in modern languages, attending Christ’s College, Cambridge (1954-57), after his national service. It was here that Bryan Robertson first spotted his work at an exhibition (the artist’s first) at Heffers bookshop.

The language of sculpture is a means to an end. It is about expressing (as Rilke puts it) without guile the way we see and feelPhillip King

King was well read and this academic background enabled him to write and speak publicly with a high degree of articulacy about his work. He was passionate about the writings of Albert Camus and Rainer Maria Rilke. He was also very knowledgeable about the history of sculpture. Reflecting on it in a lecture in 1998, he stated: “The language of sculpture is a means to an end. It is about expressing (as Rilke puts it) without guile the way we see and feel. Our emotions are involved in this process. They are part of the language that brings matter ‘to life’, and gives it the ability to move us. Through something as simple as clay form, we find the link with something greater within ourselves.”

It is a powerful observation that gives us a sense not only of how King thought as a sculptor, but also about how much sculpture and what it could offer us all meant to him.

Phillip King; born Kheredine, Tunisia, 1 May 1934; married 1991 Judy King (née Corbalis); died 27 July 2021