In the global reckoning that followed the murder of George Floyd, much was made of what museums and art institutions would do to address the imbalances and biases in their staffing, structure and programming. The contrite statements about systemic racism issued by organisations in the wake of the killing were one thing. How quickly would we see action reflecting that shift in consciousness?

As our reporting has shown, for some organisations the statements were early steps in a long-overdue process that might take years to be bear fruit. Others have been addressing the subject for years, mostly contemporary exhibition venues—kunsthallen with the advantage of not being tethered to often dubiously acquired objects and collections—and temporary shows such as biennials. In Britain, there have been slow-burning but important developments in major collections: Tate’s steady but active embracing of multiple Modernisms beyond the Western canon, for one.

But, still, as I visit museums and galleries, I am conscious that in this new era, we need to see paradigms shifting, the shockwaves of recent events translated into radical cultural moments. It has been welcome to see broader representation in museums and galleries, more active programming of artists of colour, but it seems crucial, too, that we should be able to identify institutional changes.

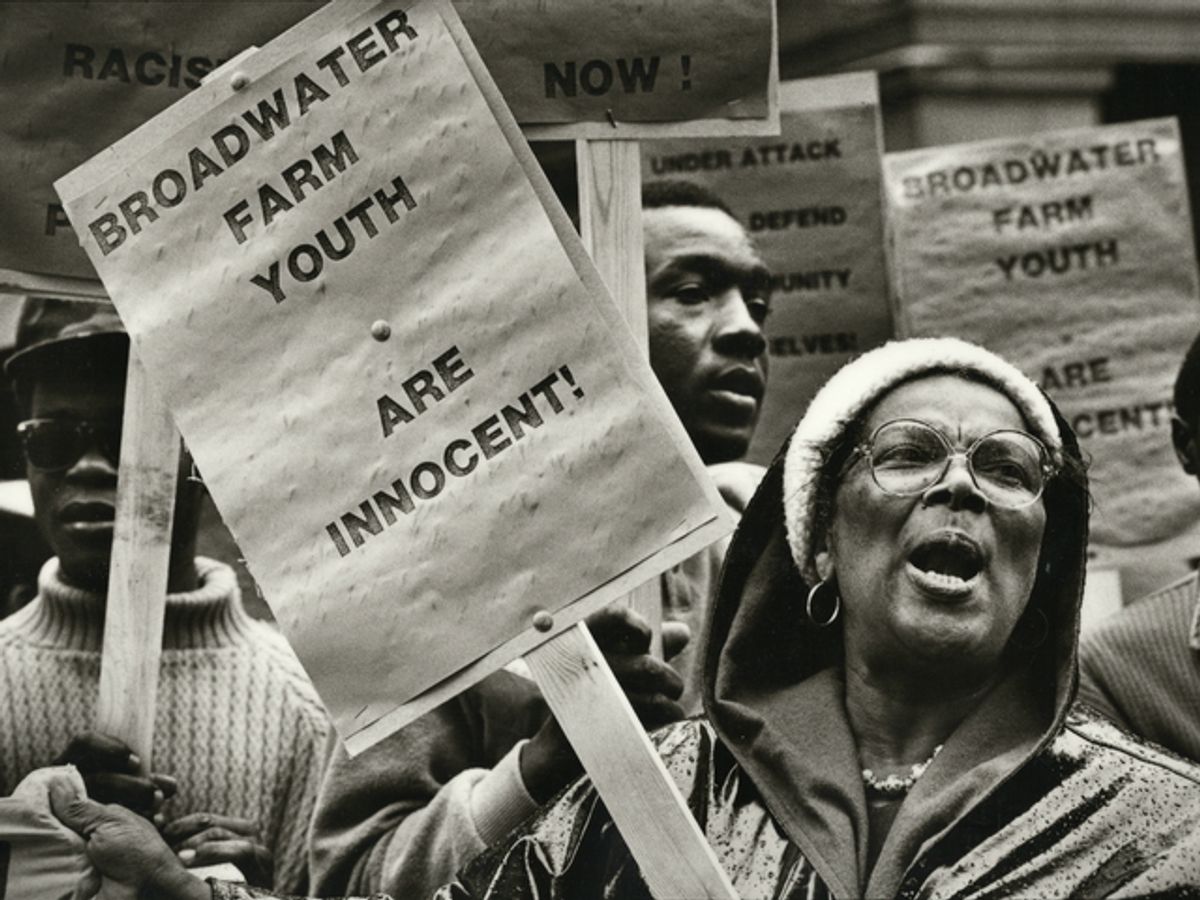

The most exemplary show I have seen was actually planned before the events in Minneapolis last year and only shown this year because of Covid-19 delays. War Inna Babylon at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), London, which presents the history of the Black experience in Britain in the post-war period, is exactly the kind of stirring exhibition experience we need. It zeroes in on the London borough of Tottenham to reflect on institutional racism and police brutality and the grassroots activism that emerged in Black communities.

Crucially, the ICA and its outgoing director Stefan Kalmár appear to have recognised that this is not a story they could tell themselves, and gave carte blanche to external curators— the racial advocacy and community organisation Tottenham Rights, together with curators Rianna Jade Parker and Kamara Scott.

The result is a show of unflinching directness. It is both empirical and empathetic—a history told through text, archival documents, photography and film, and some works of art, but also, crucially, through personal testimony and lived experience.

The dramatic conclusion to the show is the investigative collective Forensic Architecture’s multimedia analysis of the police killing of Mark Duggan in 2011, which exposes flaws in the police evidence relating to the killing. Forensic Architecture are emblematic of the show’s spirit. In an article in the Guardian written in the wake of a furore around their exhibition at the Whitworth gallery in Manchester, they wrote: “Our work is indicative of the advent of a new kind of political art: one that is less interested in commenting on than intervening in political realities.”

War Inna Babylon feels like an intervention in this sense. As cultural organisations grapple with new realities, they would do well to learn from the ICA’s example.