In his documentary Bob Ross: Happy Accidents, Betrayal & Greed, streaming in the US on Netflix from 25 August, the film-maker Joshua Rofé set out to explore not just the life of one of America’s most beloved and recognisable painters, but also the posthumous legal battle over his estate and the proceeds of Bob Ross Inc.

The company manufactures a wide range of products branded with the artist’s name and familiar Afro-ed likeness, including art supplies and innumerable tchotchkes from socks and mugs to chia pets and toasters. According to the film, none of the profits from this merchandise have gone to Ross’s family, directly against the artist’s wishes.

With interviewees including Ross’s son—who made frequent guest appearances on The Joy of Painting, the artist’s public television programme, which has become a cult favourite—and a number of his close friends and collaborators, the documentary is successful in not just looking into the morally unsound reality of these estate issues, but also in painting a picture of Ross’s life.

The film shows how Bob Ross went from a clean-cut young Air Force sergeant living in Fairbanks, Alaska to the empathetic artist with the tranquilising teaching technique we know from The Joy of Painting. The most moving details involve the ways Ross used his platform to express his often-difficult personal life (as in this clip), including the death of his wife only weeks before his own diagnosis with non-Hodgkins lymphoma.

But perhaps the most satisfying revelation from the film is that the calming, even-keeled Ross we know from TV appears to have been an authentic expression of the man himself—though the Afro, we quickly find out, was not his natural hair. Despite his personal tragedies and struggles, Ross was someone who saw the beauty in everything, and whose happy-accident outlook remains a balm for so many.

We spoke with the film-maker ahead of the release this week.

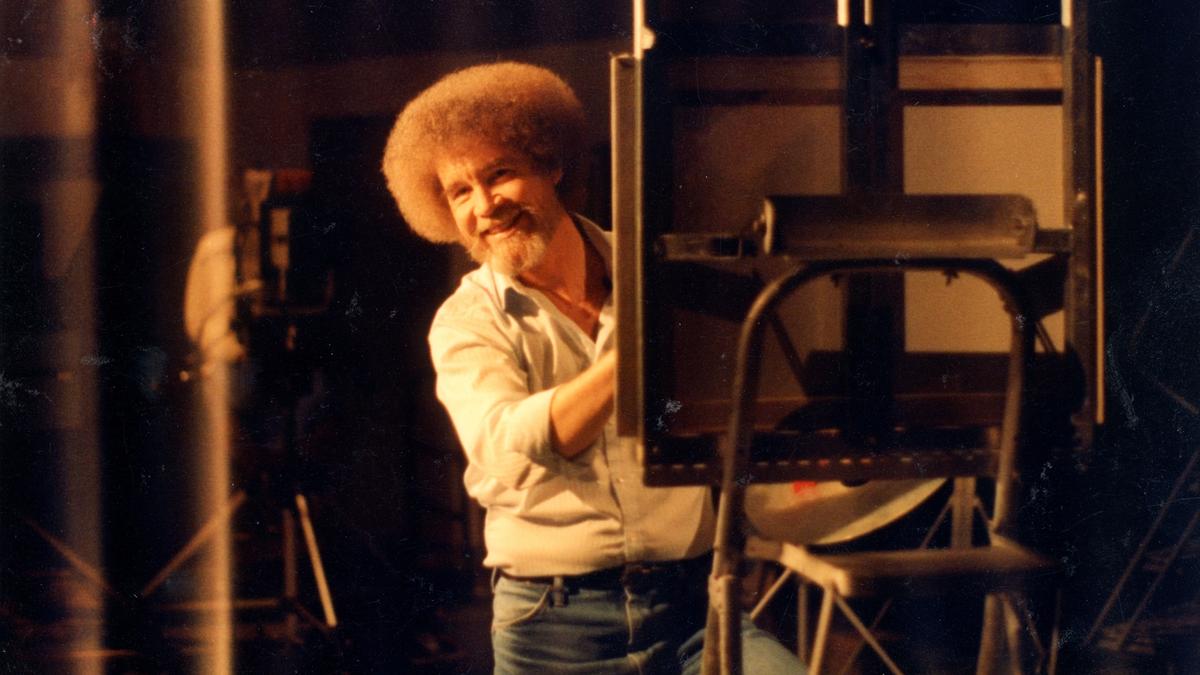

Bob Ross in Bob Ross: Happy Accidents, Betrayal & Greed Courtesy of Netflix © 2021

The Art Newspaper: How did you decide to take the project on?

Joshua Rofé: I'd been thinking about maybe making a film that explored the relationships that various American artists had with the time period that they were at the peak of their powers in. Bob Ross was one of the names I had on the list as he related to the 80s specifically. Then my producing partner Steven Berger and I had a meeting with an executive for Ben Falcone and Melissa McCarthy's production company, Divya D’Souza.

It was just one of those general meetings that gets set up to see if you vibe creatively and if there's any overlap in the types of stories you want to tell, and we were just having a great conversation about a million different things that excite us about film and art, and Divya mentioned how much Ben and Melissa love Bob Ross and that they'd given some thought about maybe making a scripted film about him, but in their initial attempt to find any information online they saw that there wasn't much, and what there was felt very curated. It certainly wasn't going to be enough to inform a screenplay and thoroughly tell somebody's story. So in that moment I said, “What if we made the doc?”, because that's kind of what we do, we find out what really went on.

So we sat down with Ben and Melissa, all of us together, and it was one of my favourite meetings I've probably ever had because there was nothing showbiz-like about it. All we were doing was talking about Bob Ross and why we were moved by him, why we thought other people were, why other people told us they were. It was just a really heartening and inspired conversation, and we walked away from that meeting thinking, “Let's do this, let's see what happens, let's see what there is.”

My team and I then moved forward trying to find people who knew and worked with Bob, and began our initial outreach. We were met with two things: one was that everybody who we spoke to loved Bob and missed him dearly, and the second was that they were afraid to talk to us on camera for fear of some kind of legal retribution. So as soon as we came up against that, we realised there was more here than we could have known, and it was really compelling. So we had to go forward full-steam ahead and attempt to tell this story.

Steven Ross with his father, in a still from Bob Ross: Happy Accidents, Betrayal & Greed Courtesy of Netflix © 2021

You note early on in the film that over a dozen individuals declined to be interviewed for fear of litigation. How did that affect the filming process?

There's something amazing about telling a story that people literally cannot Google. Bob's real story, particularly when we were starting to work on this, was exactly that. At first I couldn't believe we weren't going to get certain people—five people dropped out literally one or two nights before we were going to interview them, we'd flown all this way—and then I just remembered that this was why we started. We knew we had to tell this story when we found out people were afraid to talk. Those that were willing to talk, their voices were so valuable, their bravery and defiance in the face of any of that fear. I think it's amazing that here you have this icon and you can get maybe only seven or eight people to tell you what was really going on. Ultimately it became a strength, and it became the very reason to tell the story.

Throughout the film, you incorporated a lot of footage from The Joy of Painting. Because there are quite literally hundreds of hours of footage available, I'm curious what it was like to work with all of that material?

I want to give credit to the two people who did that, co-producers Caitlyn Hynes and Lukas Cox, they literally watched every single episode of the show. They catalogued all these incredible moments that out of context, if you don't know what was going on in Bob's life, may not hit you the way they do if you knew what was happening. It was wild to look at all these moments that seemed to not be infused with any sort of intensity or anger, but once you knew [his personal story] you realised he's expressing anger—even if it's veiled under the very specific guise of the show or the moment he's in in the painting—he's screaming at the top of his lungs in the only way he can. That was incredible. There was a point where I was watching all these episodes at night before bed, just writing down which episode it was from which season and the time code and the quote from him and I was just blown away by how much he was saying. Again, if you don't know what's going on in his life, you'd have no idea.

A still from Bob Ross: Happy Accidents, Betrayal & Greed Courtesy of Netflix © 2021

Obviously much of the content around the issues of the estate are upsetting, but the uplifting qualities of Bob Ross himself seem to almost overpower the other nefarious content.

I'm so glad you said that. Yes, there's a lot of darkness in the film and a lot of upsetting things, and you can definitely feel Bob's pain viscerally, but at the end of the day, the things that make Bob magical seem to transcend and triumph over all of that. When you see what he left behind, which are essentially the responses from the masses, I find it so moving. His art, and what made him special, that's what won out. Sure you can go back and forth all day around the legal case and the morality and all of the turmoil around that, but at the end of the day, if a person puts on Bob's show and watches him do his thing, everything else melts away.

What do you think is behind Bob Ross’s staying power? Why does he remain such a part of the zeitgeist nearly 30 years after The Joy of Painting ended?

Bob has this thing that a lot of icons have, which is some quality that allows us to transpose whatever we need onto them. They can be whatever we need them to be. I spoke to people who had really wildly different stories about what Bob meant to them. I spoke to one person whose parents were going through a divorce and home life was rough—they were a teenager at the time—and when they would come home from school they'd put on Bob Ross, and for those 30 minutes they were not worried about the fighting in the house and all of that pain. I spoke to another person who said they and their friends would get together after school, smoke some weed, eat some chips, turn on Bob Ross, and just veg. Bob could be whatever you need him to be, and the common denominator is that you will feel better, you can unplug from angst and whatever challenges you are in the midst of. Maybe not completely, but to some degree. He provides a reprieve that is so specific and so unique that it seems to transcend so much.

A still from Bob Ross: Happy Accidents, Betrayal & Greed Courtesy of Netflix © 2021

The documentary ends on a moment that celebrates Bob Ross's enduring positive impact on the world. I'm curious about your decision to end on that note.

It goes back to what I was saying about how Bob's magic seems to transcend all. There's a great quote towards the end of the film from [the artist’s son] Steve Ross where Bob says something to the effect of: "It's not only about what we do while we're here, but how people remember us when we're gone". Look at how people continue to respond to Bob Ross with such love and affection. What made him special really is what rules the day at the end of this story.

What effect do you hope the documentary will have, whether it’s on the issues of the estate or not?

My real hope with the documentary is that people will view Bob in a much deeper way. In a way that is really infused with a ton of emotion and empathy. He's more than the 30 minutes on the show and more than a meme, he was a deep-feeling person who experienced a lot of tragedy and hardship in his life, but also a lot of magic. Many moments of his life were inspired and beautiful, so I just hope above all that people feel a deeper connection to him.

• Bob Ross: Happy Accidents, Betrayal & Greed, directed by Joshua Rofé, 1hr 33min, is on Netflix, from 25 August