The Art Newspaper's XR Panel

What exactly is extended reality (XR) and how is it being used in art? We bring together an international group of experts in the field to review and make sense of the cutting-edge, digital work that artists, museums, galleries and app-makers are creating across the spectrum of XR—from augmented to virtual reality.

Each XR review gives an overview of a project and a statement from the creators before our expert panel rate it based on ease of use, how good the art is, the medium-specific qualities it employs and whether it breaks new ground. Read all our XR reviews here.

The Glass Drawing Room of Northumberland House, London, reconstructed in virtual reality for the Corning Museum of Glass

The Glass Drawing Room, Northumberland House

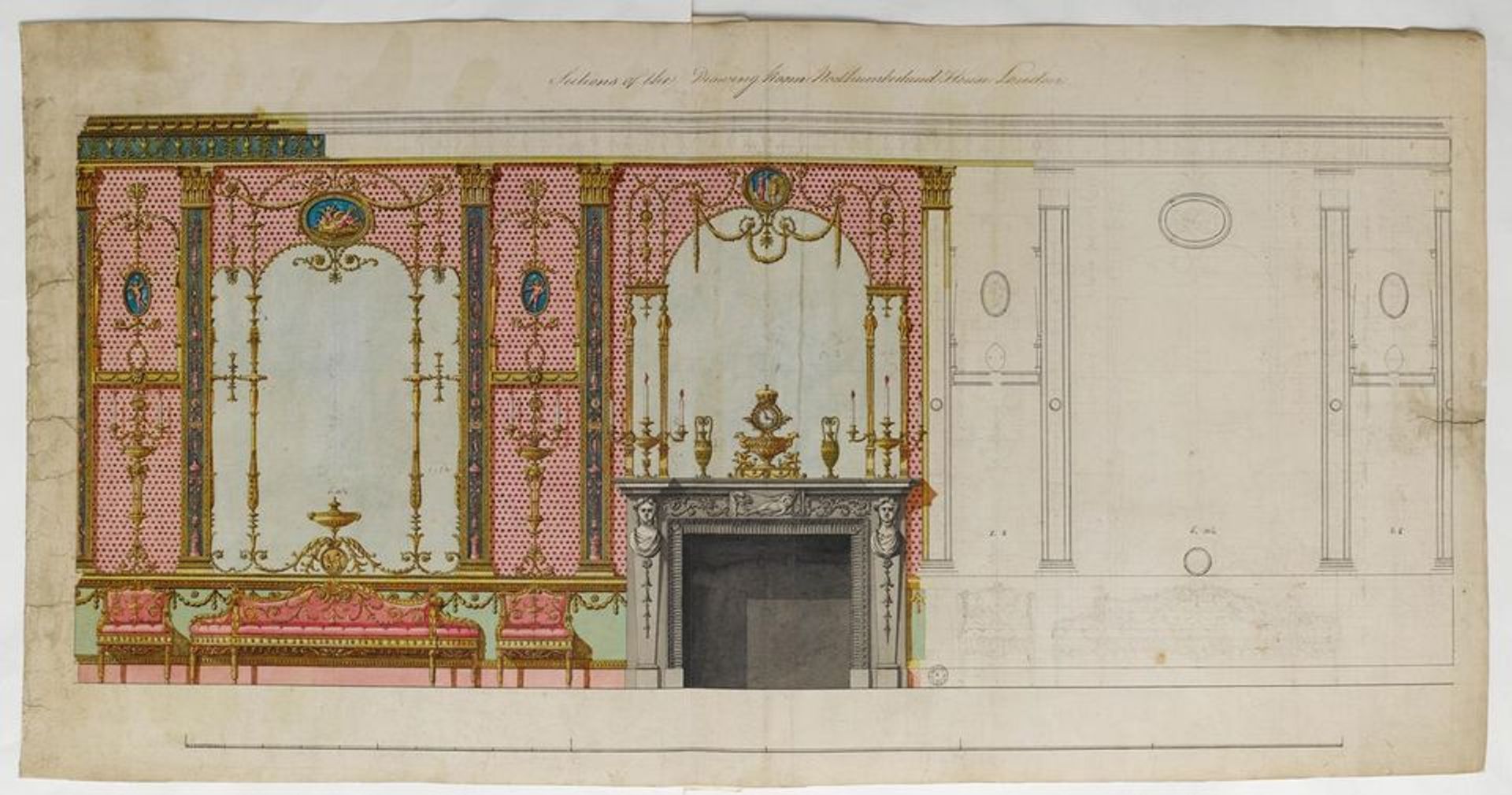

This recreation in virtual reality of the Glass Drawing Room from Northumberland House, London—a room designed in 1775 by the architect Robert Adam for the town residence of the Percy family, Dukes of Northumberland—was produced by the Corning Museum of Glass in New York as part of the loan exhibition In Sparkling Company: Glass and the Costs of Social Life in Britain During the 1700s (until 2 January 2022).

Produced by:

Mandy Kritzeck and Scott Sayre of the Corning Museum of Glass's digital team, who managed the project with Kit Maxwell, Curator of Early Modern Glass.

Dr. Adriano Aymonino, of the University of Buckingham, provided research on the room’s paintings and iconography.

Made by:

John Buckley, Niall Ó hOisín, Klemens Kopetzky and Aaron Deevy at Noho, digital experience producers based in Dublin, worked on the development of the VR.

Maria Roussou, Hara Sfyri, and Dimitris Nastos from Makebelieve, an interactive experience design and consulting company based in Athens, worked on the research, modelling and design.

Tom Hambleton, of Undertone Music, based in Minneapolis, Minnesota, composed the music and sound design.

Where to find it

- As a full-VR experience for Oculus Quest or Oculus Rift. You can download the apk file

- As a VR experience on site at Corning Museum, as part of the exhibition In Sparkling Company. The exhibition includes loans from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), in London: and Sir John Soane's Museum, in London

They say:

The programme was designed to run on the low-cost Oculus Quest headset, making it accessible to a broad publicCorning Museum of Glass

We say:

The makers of the Corning experience have used a project with serious scholarly underpinnings to deliver a narrative-free experience that aims to tell a story through material-sensory emotions aloneLouis Jebb

Curator's note

The context

The glass drawing room at Northumberland House, London—which stood at the junction of what are now Northumberland Avenue and Trafalgar Square—was completed in 1775 for Hugh Percy, the first Duke of Northumberland (1714-86), to designs made by the architect Robert Adam. The room was modified in the 1820s and dismantled in 1874, before the house was demolished.

Kit Maxwell and his colleagues at the Corning Museum of Glass drew on a rich collection of historic materials to inform the recreation of the original interior in VR. Some of the glass panels survive in the collection of the V&A in London. They have now been restored and a section of them loaned to Corning for the physical exhibition at the museum. The VR project also made use of Robert Adam's surviving drawings for the room, which have likewise been loaned to the exhibition by Sir John Soane's Museum in London.

Robert Adam's drawing of a section through the Glass Drawing Room Courtesy of Sir John Soane's Museum, London

Before Northumberland House was demolished, the chimneypiece and some of the furniture was moved to Syon House, the Percy family's riverside estate in west London, across the Thames from Kew Gardens. The duke's descendants have conserved the surviving pieces from Northumberland House.

The project team travelled to London—before the Covid-19 pandemic—to measure and photograph the room’s surviving elements at the V&A and at Syon. They made a fascinating discovery while examining the seat furniture in storage at Syon: the 1820s upholstery had begun to peel away, revealing the original 1770s textile, for which there was no original description.

When you see this chintzy pattern in VR, on a chair placed next to a pietra dura console table top with its own floral patterns, and against the view over the house's wooded and terraced gardens leading down to the Thames, the newly discovered history of the room's upholstery makes elegant sense.

The fabric on the drawing room's chairs was reconstructed digitally from the original 1770s pattern, discovered on the furniture—in store at Syon Park, London—under a later fabric added in 1820

The programme

When the latest incarnation of VR hit the headlines in 2014—after Facebook acquired the headset maker Oculus Rift—one of the many curatorial possibilities that excited me was one of creating ideal rooms for the telling of stories or recreating historic lost rooms and lost spaces, from the library at Alexandria to Leonardo da Vinci's studio. What one might call the Wunderkammer approach to VR.

Seven years on, the Corning's deeply researched recreation of the glass drawing room from Northumberland House feels like one of the most ambitious "Wunderkammer" projects of its kind. It is pioneering for the range of sources that have gone into creating it, and the museum-standard approach to getting the details right. The room itself well illustrates the Corning exhibition's concern with 18th-century glass as a symbol of wealth, a metaphor for polished manners, and the product of Britain's imperial expansion in the 18th century. The personal wealth of aristocrats like the Duke of Northumberland depended heavily on the exploitation of slave labour in sugar plantations of the West Indies and the huge profits made by the East India Company in using the resources and population of the Indian subcontinent.

What intrigues me is the Corning Museum's decision to limit an information overload for the viewer: to confine the viewer's experience to the sensory. There are no captions and no voiceover but an emphasis on light, colour and sound in the recreation of a room designed for visual effect and visual games, like the windows overlooking the river Thames seen against the mirrored walls surrounding them. Glass, light and more glass in a room made for show.

The producers of the Corning experience have thus used a project with serious scholarly underpinnings to deliver a narrative-free experience that aims to tell a story through material-sensory emotions alone. It's an admittedly well-mannered way—after the pandemic-era emphasis on viewing rooms and virtual recreations of curated exhibitions—to get back in touch with the visceral essentials of VR.

Louis Jebb

Is it accessible?

This dedication to accessibility is very commendable and should be industry-standardEron Rauch

The drawing room can be explored in night or day mode

Louis Jebb: Our panel's experience shows the lasting challenges of distributing high-quality, fully immersive VR projects.

The Corning experience works on the Oculus Quest 2—a wireless headset that leaves you free to wander at your will, and which has sold (for $300 or £300) an estimated 2.5 million units since its launch early in 2020. Facebook Oculus can claim, with such sales figures, that the Quest has seen their headsets break into the mainstream. And Corning's decision to develop the app for the Oculus store was a logical one given their aim of maximising a combination of visual quality and viewer accessibility.

But there remain points of friction for both developers and users:

- The Oculus Store approval process: The development team at Corning submitted their app to the Oculus app store in the hope of having it ready for the launch of the exhibition in May 2021. As of late July 2021 they were still awaiting approval. Two of our panellists have reviewed the experience by sideloading into their Oculus headsets a downloadable version of the app, which is available to all on the museum's website.

- The variety of specifications in the Oculus family of headsets: Two of our panellists, equipped with Quest 2 headsets, managed the sideloading, and were able to review the app. A third panellist, Dhiren Dasu, has a Quest 2 but was unable to get access on his account, and therefore had to withdraw from the reviewing process. A fourth panellist—Seol Park—has an Oculus Go, a version of the company's VR headsets that it recently stopped marketing or supporting, and which lacks the specification to show applications built for Oculus Quest. She, too, therefore had to withdraw from the reviewing process.

Carole Chainon: Users need to have access to an Oculus headset in order to try this experience. While headset sales have increased during the pandemic, not everyone is equipped to experience it.

Eron Rauch: The Corning Museum has made multiple versions of the project, with many accessibility features. Though I only had access to the development Oculus app so I couldn’t test them, this dedication to accessibility is very commendable and should be industry-standard.

One VR/AR-specific issue that can block some users from experiencing the app is the rather significant buffer between the area of the floor where you can stand and the walls. In tightly bounded play-spaces, like my Los Angeles apartment living room, this makes it impossible to get close enough to the objects to really press your nose to them.

From a critical, art historical standpoint, how good is the art?

I believe this format will become the standard with physical arts, whether for individual works, homes or rooms of historical importance, recreated and preserved for all to experience digitallycarole chainon

Carole Chainon: I believe this format will become the standard with physical arts, whether for individual works, homes or rooms of historical importance, recreated and virtually preserved for all to experience digitally. (The developer files for this project will eventually be made available by the Corning Museum on Github.) Ownership of these digital recreations will be an important topic as well as whether or not they will always be made available to the public. Historically relevant digital assets could be made available for anyone to use/experience allowing artworks to be “fully” democratised.

Eron Rauch: Exploring benchmark craft objects from the ultra-wealthy tycoons and historical imperialist nobility always evokes very mixed reactions from me. However, I am always astounded at the skill and imagination of the craftspeople who provide such theatricality with a table or a moulding. I want to hear their stories, their journeys and their inspirations.

What medium-specific qualities does it employ?

When in front of a mirror, not seeing my (or, a) virtual reflection unfortunately takes away the sense of presence and feeling of immersionCarole Chainon

Carole Chainon: This experience is a great example of the use of VR in order to preserve locations that no longer exist and immortalise objects of historical importance. The glass chandeliers are extremely well recreated. The menu is minimal, with a focus on the sole experience of the room. I appreciated at times not having a voice-over in order to experience the room, as if I were physically strolling through it, however, I would have enjoyed a virtual guide feature in order to take full advantage of the VR setting. I also enjoyed the lighting change from day to night. When in front of a mirror, not seeing my (or, a) virtual reflection unfortunately takes away the sense of presence and feeling of immersion.

Eron Rauch: The idea of recreating lost or mythical spaces in scintillating—literally in this case—detail is extremely exciting to me. While static documentation is useful, as Tadao Ando’s work so clearly showcases, architectural spaces are always felt in an embodied way, unfolding in meaning as we move, look, notice, move, constantly. Inhabitation instead of visitation is a powerful driver of understanding, and not just factual data.

Does it break new ground technically?

While I was really excited by the concept of the project, I was disappointed in the technical executionEron Rauch

Working with mirrors is one of the biggest technical challenges of the VR experience

Carole Chainon: Reflective surfaces and glass can be difficult to capture digitally, so the team did a great job both on the capture and digital recreation, as well as to create the feeling of depth when looking into the mirror. The rendering quality is quite high though current headsets still provide a pixelated view when we get close to the objects/textures and paintings.

Eron Rauch: Frankly, while I was really excited by the concept of the project, I was disappointed in the technical execution. I have a couple of pages of notes about various issues I noticed, but the most striking problem is that mirrors’ reflections are so wrong—constantly splitting, wobbling, and shifting out-of-sync with my eye tracking, including inaccurately spatialised 2D masking to try to carve out space for the room-objects—that they induced such VR motion sickness I had to regularly stop and stare at the floor to prevent feeling ill.

Since I spent a lot of time staring at the floor, that led to dwelling on another major issue: resolution. The ceiling, floor, outdoors and other sections used very low-res 2D texture maps that rendered the paintings on the ceiling, for instance, borderline illegible. A much smaller, but telling problem is a lack of an exit button in the main menu and no statement of how to quit the app in the help, requiring you to know how to force quit the app from the Oculus system menu.

What does it say to you about the future of the medium within the art world?

This isn’t to discourage creators from the valuable work of recreating lost digital spaces, but rather to encourage them to make the "feel" right, not just deploy accurate dimensions and texturesEron Rauch

Eron Rauch: To delve into the philosophical virtual wilderness a bit, the load screen has a version of the room, but stripped of its realistic surfacing, leaving just the plain white geometric panels of the underlying 3D models. After immediately making the nerdy connection to the white room at the end of 2001: A Space Odyssey, a fleeting thought got stuck in my mind: this obviously digital version of the room was far more “believable” and “immersive” than the rendered and textured version. Maybe it’s because I just watched the film critic Shannon Strucci’s YouTube video on the complicated history of the uncanny valley, but future (re)creators of historical architectural spaces are going to have to attend to the problem of what you might term “the uncanny veranda”. A digital ceiling that does not pretend at tactility will arrive at “true” feeling much more easily than the finely detailed, multi-material gilded, frescoed ceiling. This isn’t to discourage creators from the valuable work of recreating lost digital spaces, but rather to encourage them to make the “feel” right, not just deploy accurate dimensions and textures.

The XR panel's ratings

The panel thought it important to give notice of this piece of work, but that it would be unfair to give a star-rating because of the issues that remain in the distribution system.

The Art Newspaper’s XR Panel

Gretchen Andrew is a Search Engine Artist and Internet Imperialist who hacks powerful systems with art, code, and glitter. You can see her current VR exhibition on Artland.

Carole Chainon is the co-founder of JYC, a XR development and production studio based in LA with a presence in Europe, creating XR experiences for the entertainment and enterprise sector. She is also a Spark AR Creator.

Louis Jebb is a writer, editor and producer of content in virtual reality. He set up The Art Newspaper’s XR Panel in 2020. In 2014 he founded immersiv.ly, a maker of news content in virtual reality.

Eron Rauch is a writer at Riot Games, an artist, writer, and curator whose projects explore the infrastructure of imagination, with a focus on subcultures, video games, and photography history.