Connoisseur: “Noun. An expert on matters involving the judgement of beauty, quality or skill in art, food or music.”

There you have it, at oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com. The definition smacks of male-dominated class privilege, an outmoded relic of Georgian England.

“Connoisseurship was born in the 18th century out of a legitimate desire to cultivate and promote knowledge about the arts, but it was also very much a boys’ club,” says Terry Robinson, an associate professor of English and drama at the University of Toronto. “Membership in this club—the Society of Dilettanti—was exclusive, open to only a select group of people, which de facto necessitated the exclusion of others,” adds Robinson, the author of the 2017 essay Eighteenth-Century Connoisseurship and the Female Body.

“Connoisseurship” is a C-word long fallen out of usage. Now issues of identity, race and gender, rather than art-for-art’s-sake aesthetics, dominate the discourse of today’s art world. It, too, has its codes of exclusivity, but the art under discussion has not been made in the distant past, but in the here and now by artists whose diversity and commercial success would have bewildered the Society of Dilettanti.

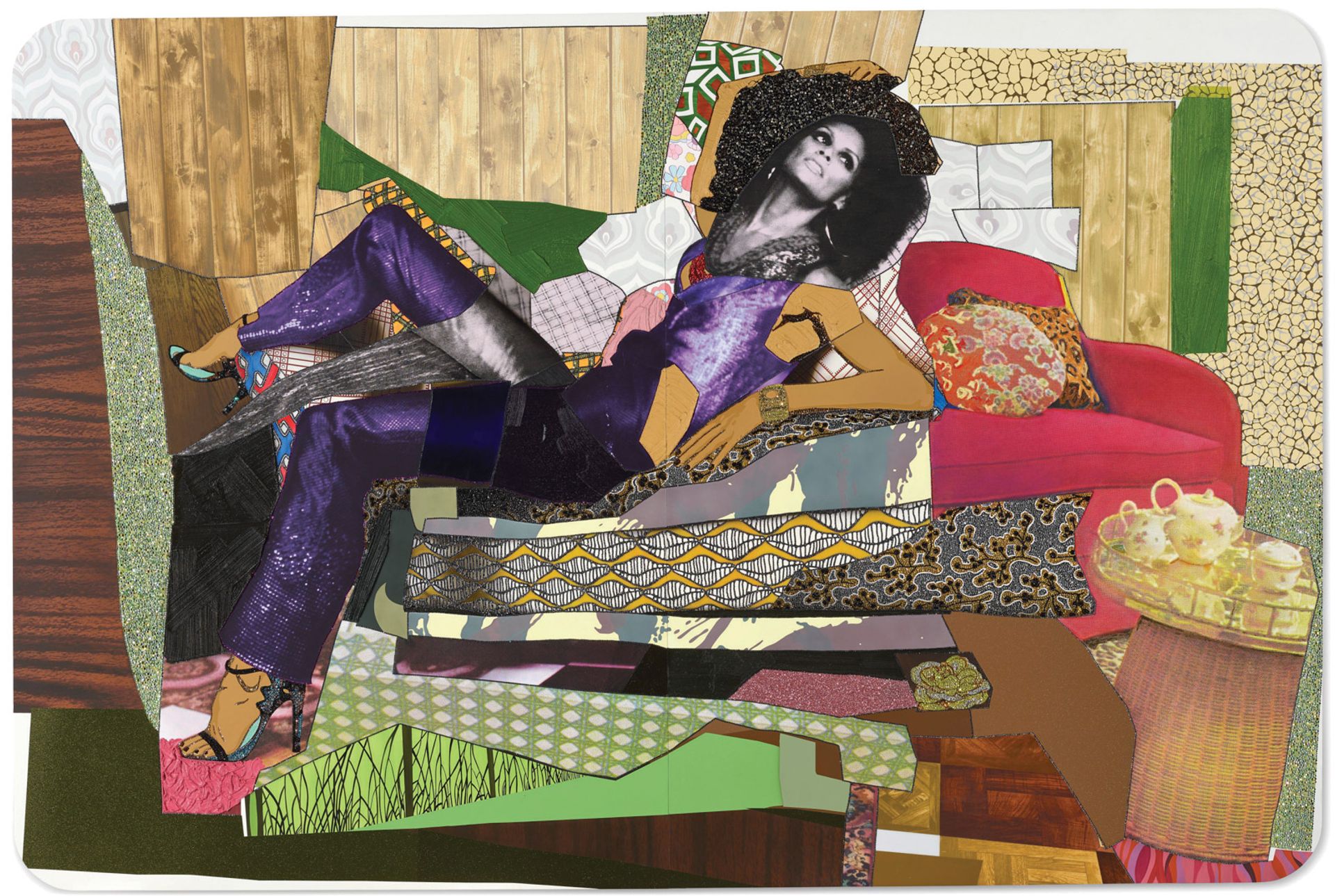

Unlike the early-2010s, during the craze for so-called “process-based abstraction”, when $300,000 for a Jacob Kassay or a Lucien Smith was regarded as an eyebrow-raising auction price, works by the latest breakthrough artists are now selling for millions. Amy Sherald ($4.3m), Mickalene Thomas ($1.8m), Emily Mae Smith ($1.4m), Loie Hollowell ($1.4m) and Amoako Boafo ($1.2m) are among the names whose prices have soared to record levels at recent auctions in New York, London and Hong Kong, turbocharged by internet-enabled bidding from across the world.

Last decade, the speculative boom for Minimalist abstraction had its critics. Works by hot young names such as Seth Price, Oscar Murillo and Parker Ito were dubbed “Crapstraction” and “Zombie Formalism”. Prices collapsed in 2015.

Auction success: Mickalene Thomas’s Racquel Reclining Wearing Purple Jumpsuit (2016) © Christie’s Images LTD, 2021

The global seal of approval

Today’s new wave of artists of the moment still use the millennia-old medium of painting, a genre that has always invited qualitative comparison, but this time round the global scale of the auction prices has become its own seal of approval. As in the 2010s, “flippers” can make more than 20 times what they paid for the works in galleries.

“We confuse economic value with historical value,” says the Italian curator Francesco Bonami, who directed the 2003 Venice Biennale. The system is “not really working”, he says. “Nobody’s subverting anything anymore. It’s become extremely self-celebratory.”

Filip Vermeylen, a professor of global art markets at the Erasmus School of History, Culture and Communication in Rotterdam, thinks there is a case for connoisseurship to make an updated comeback. “The market thrives on these hypes, these flavours of the month,” says Vermeylen, the co-author of the 2012 essay The End of the Art Connoisseur? Experts and Knowledge Production in the Visual Arts in the Digital Age. “We’re now in an extreme situation. We’re not allowed to talk about quality anymore. All you need to know about the value of a work of art is its price. I’m concerned about the loss of connoisseurship.”

According to Vermeylen, “we need to bring connoisseurship into the 21st century” now that algorithms, speculators and the market increasingly determine the value of art. “It needs to be far more inclusive and use new technology to make it less subjective.”

But the problem, as Vermeylen acknowledges, being a college professor, is that our relativist, post-structuralist art education system is now much more preoccupied with issues of identity, race and gender than what might make one work of art more historically significant than another.

In addition, Vermeylen, along with many other people, is concerned about the way in which the institutions that could nurture more diverse critical thinking about the arts are being eroded and undermined. “It’s very troublesome when you hear about American universities closing down humanities departments,” he says. The classics department at Howard University in Washington, DC, the only such department at a historically Black college, is being dissolved.

“Picasso could do no wrong, because whatever he did was never examined.”John Berger

In the UK, Gavin Williamson, the education secretary, has called for a wholesale reduction in “low value” humanities degrees, like history of art, which would make the discipline more elitist than it has ever been. Private Eye magazine recently reported that the cash-strapped Victoria and Albert Museum has permanently laid off the experienced painting curators Katherine Coombs, Ana Debenedetti and Mark Evans. The museum has declined to confirm the report.

And so, just as in the days of Joshua Reynolds, if a newcomer wants to confidently engage with the commercial art world, they go to “trusted intermediaries” such as the major galleries, advisers or auction houses. “They give a quality certificate,” Vermeylen says. “The art market’s systems have not changed dramatically since the 18th century.”

Bomi Odufunade, a London-based director at Goodman Gallery, is one of these intermediaries. “It’s about trying to use your gut,” she says. “We try to envisage the longevity of a career. Can we see this at Tate Britain in 20 years? You have to try to work out who is going to last the course.”

Odufunade is gratified that the dynamic of the market has shifted, particularly towards artists of colour. “I find it refreshing. When I started out there was nothing. There was a lack of Blackness on the canvas. At this moment, there are so many great artists of colour,” she says, conceding, though, as with any generation of artists, some will stand the test of time better than others. “When I see auction prices go crazy at an early stage, I worry,” she says. “History tells us that it doesn’t end well. You want steady growth. But sometimes it’s good to have a bit of rock-and-roll.”

Odufunade and other intermediaries select works to be shown, leaving time, ultimately, to do the judging. It is not in the interests of anyone involved in today’s art world to be openly judgemental.

But in the past, influential critics have stuck their necks out. In 1965, when Picasso was at the height of his fame, John Berger wrote the book Success and Failure of Picasso. In Berger’s view, the towering genius of 20th-century art had been in a state of creative decline since 1944. “Picasso could do no wrong, because whatever he did was never examined,” wrote Berger, describing the artist’s later years. “Picasso is only happy when working. Yet has nothing of his own to work on. He takes up the themes of other painters’ pictures,” he wrote, referring to the Femmes d’Alger series (1954-55), inspired by Delacroix. “He decorates pots and plates that other men make for him. He is reduced to playing like a child.”

The record auction price for a Picasso is still the $179.4m paid for the 1955 painting Les Femmes d’Alger (Version ‘O’), back in 2015. Picasso’s “childish” ceramics have sold for more than $2m. So much for time, the critical examiner. Picasso can still do no wrong.

“Artistic knowledge came to be defined in many ways as the province of a small, privileged group of white men, whose putative cultivation and discernment granted them the right to hold the cultural reins,” Robinson says. “This legacy has long been with us.” That legacy was still going strong in the 1960s, when men like Berger, Clement Greenberg and Kenneth Clark held the cultural reins.

“There will always be a case for analysing and evaluating artworks with critical and intellectual rigour,” Robinson says. “But understanding what makes an artwork significant, compelling, or valuable should not ultimately be defined by just one person or one group.”

But in the current cultural and commercial climate, in which the critical evaluation of art feels like a throwback to the 1960s, or even 1760s, these definitions will remain in short supply. Somehow time will have to do that job.