It was a happy accident that led Dolly Kola-Balogun to enter the art world. Born in the UK but raised in Nigeria, Kola-Balogun studied political science and sociology at universities in Boston and London. She comes from a family of prominent lawyers, so art was not on her radar at first. “While I was at Kings College [University of London], I attended 1-54 Contemporary African art fair,” she tells The Art Newspaper. “I would go and be enamoured by the amazing artists on display and it dispelled any notions that I had had about what African art was and what it can be.” But she was disappointed to see that most of the artists were not represented by galleries in Africa. “There was a vacuum that needed to be filled,” she says. It was then that Kola-Balogun decided to start her gallery Retro Africa in the city of Abuja.

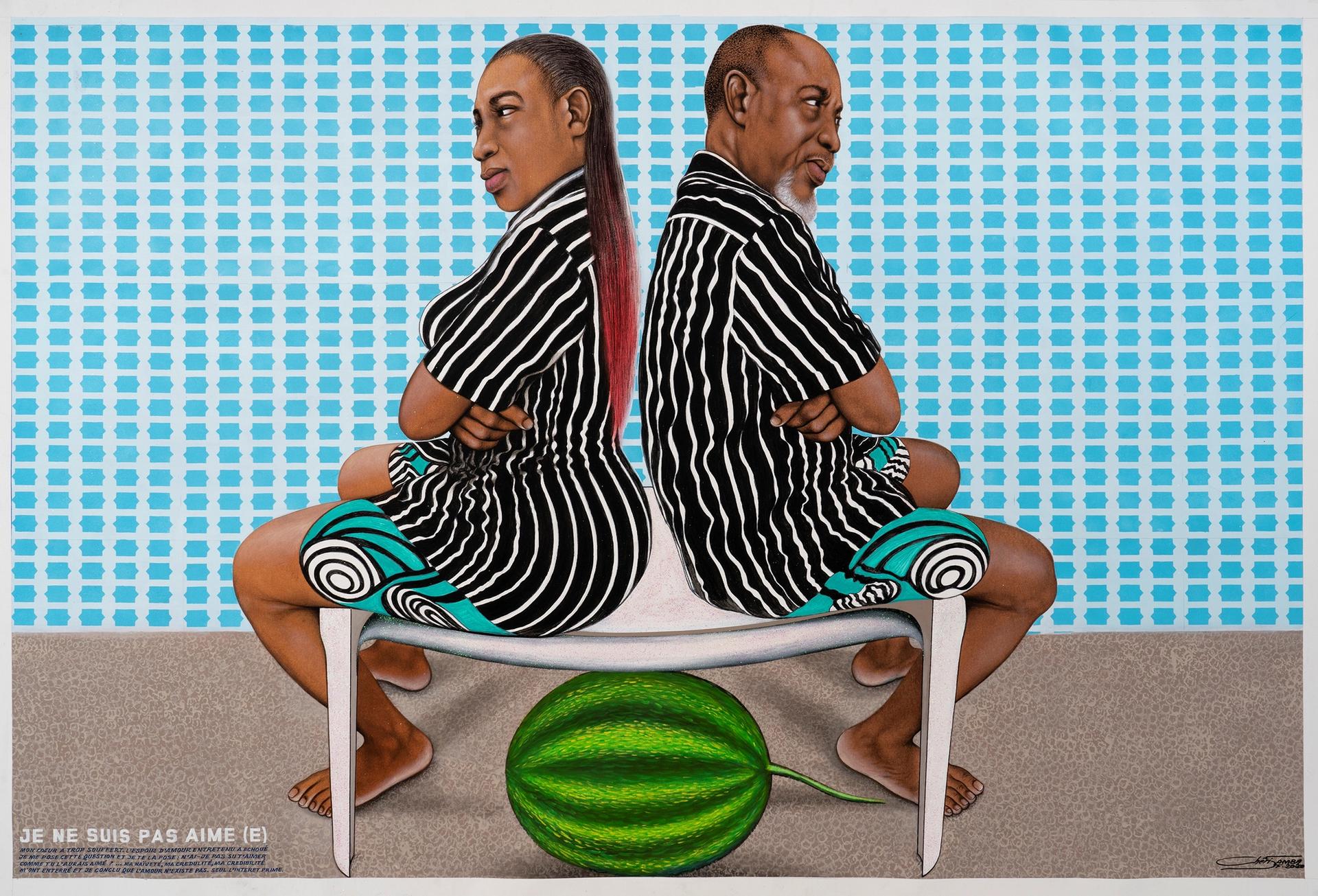

Chéri Samba's Je ne suis pas aimé (2020) © Florian Kleinefenn; courtesy of Retro Africa and Galerie MAGNIN-A, Paris

Now, Retro Africa is one of Nigeria's leading contemporary art galleries, representing African artists from all over the continent and beyond. The gallery regularly participates in the very art fair that inspired its creation. This summer Retro Africa is collaborating with Lehmann Maupin for its first group show in New York, exhibiting gallery artists Victor Ehikhamenor, Chéri Samba and Nate Lewis (Do This in Memory of Us, Lehmann Maupin, West 22nd Street gallery, 19 July-17 August). “The show exemplifies Retro Africa’s mission to advance contemporary African art by showcasing work that expands the multitude of African expressions throughout the continent and abroad,” Kola-Balogun says.

We spoke to Kola-Balogun about making a name for herself as an industry outsider; her expansion plans to Miami and Seoul; and how she is helping to build a contemporary art scene in Nigeria.

Installation view of the Go Digital exhibition at Retro Africa in 2019 Courtesy of Retro Africa

You’ve achieved a lot in the art world already at the age of 27, especially without a formal arts education. How did you go about building your profile and business?

My age was initially a point of insecurity that eventually turned into a point of pride for me, especially in the art scene where I am often surrounded by people who are twice my age and who have been in the scene for far longer than I have been. But I have enthusiasm and passion on my side. What allowed me to draw my path was the help and guidance of mentors, including the late Nigerian curator Bisi Silva, who actually gave me my first internship in the industry at Lagos Centre for Contemporary Art. And I subsequently then worked with different institutions, along with my business partner Igo Diarra, who is the director and curator of Galerie Medina in Bamako, Mali.

Retro Africa participating at 1-54 London in 2018 Courtesy of Retro Africa

We went on to organise an exhibition on African artists together at the Gennadius Library in Athens, Greece, as part of Documenta 14. That was my second major international opportunity and it allowed me to not only build a network amongst some of the most interesting and inspiring curators from the African continent, but also build relationships with artists that I still have relationships with today. That was a great inspiration to me. It broadened my horizons in terms of what I thought was achievable on a global scale.

I continued running Retro Africa at the time; we didn't have a physical space so we acted as a pop up gallery hosting exhibitions in unconventional spaces. We began to participate in art fairs like Art X Lagos and 1-54. Through that, we were able to build an international collector base; work with artists that we had long admired; and, eventually, build our own space in Abuja.

Retro Africa was redesigned by Kola-Balogun's in collaboration with her sister, who is an architect Courtesy of Retro Africa

Your sister is an architect and helped you to build the gallery. What is the space like?

My sister Olayinka Dosekun-Adjei also comes from an academic background like myself but she retrained as an architect and decided to move back to Nigeria and start her own architectural practice, Studio Contra. Redesigning the Retro Africa gallery was a collaborative process between us. We wanted to create the hub and not just the gallery space, so we have a we have a café that is a pretty popular space in Abujato hang out. There is also a four-room boutique hotel which you can get to through the gallery. We created these different elements because we thought about how best to get people to engage with the art world, and we realised that Abuja is a very social space with a lot of restaurants and bars, and a lot of people traveling to the city for business. We wanted to capture that audience as well; to have people come in just to grab a bite or a drink after work or to staying the night, but then immediately immersed in the gallery, unknowingly or unintentionally.

One fo the four hotel rooms that are part of the Retro Africa space Courtesy of Retro Africa

Have you ever sold works that way?

Yes, we do. Often, actually.

The cafe and hotel aspect of the gallery are interesting—do they help keep the gallery financially viable?

Yes, definitely. They help subsidise the gallery but are also a great revenue generator. The good thing about opening the gallery space was that we had already established a name for ourselves as a platform beforehand, so it wasn’t an entirely new investment. So some of our collectors were happy to have a space that they could kind of call home, where they could experience Retro Africa on a daily basis as opposed to sporadic pop ups here and there. It was important to have a space people where people could come to me and meet the curators in order to discover art.

The cafe at Retro Africa Courtesy of Retro Africa

Do you see the gallery expanding to other cities in Nigeria, or to other countries?

I see the gallery expansion in three phases. First, we've been building our reputation and developing both a local and international audience. We're now entering into the second phase, which involves expanding to different cities. Our plan is to open Retro Africa in Miami by the end of 2022.

Why Miami?

My reasons for choosing Miami are similar to why I opened a space in Abuja: I want space where I can define the art scene on my own terms, where the gallery is able to stand out; and a place that will give opportunities, not just to the gallery name, but to the artists that we represent. That is why we set up in Abuja and not in Lagos. We are still part of the scene there, most of our artists live in Lagos, and I travel there on a monthly basis but my hub and my headquarters is in Abuja.

Miami seems like a retro space and like a place that we could really make a name for ourselves. It also feels a bit like home—the weather is similar to Lagos, it's beachside, and it's also very ethnically diverse, which I think will make the community more receptive to African art. It has Art Basel and all the other satellite fairs. But more importantly, I think that the US market is where contemporary African art will ultimately thrive. I think that the US has been slow to pick up on African art but once it does—and it's about to—there will be a fire ignited and it will be unstoppable. I think we are currently at the beginning of the golden age of contemporary African art and the market is ever-expanding.

Installation view of the Un-Told exhibition at Retro Africa in 2020 Courtesy of Retro Africa

What’s the third phase?

Eventually I’d like to expand to East Asia. Currently, there's very little competition and very little collaboration between Africa and East Asia; it seems like our cultural exchange is filtered through the West. Even some of our most notable artists from the continent have had very little, if any, exhibitions, institutional support and participation in art fairs in Japan, China and South Korea. Despite the fact that, in my opinion, contemporary African art is actually perfectly aligned with the East Asian aesthetic. I'm considering participating in a fair in Shanghai at the end of the year and I would love for us to be part of Art Basel in Hong Kong. Asia has the biggest number of collectors and is the largest growing demographic in the art scene in general. I think if you ask any major galleries in New York or London, increasingly, many of their patrons are from that region.

If I had a gallery in East Asia, it would be in Seoul, South Korea. And that’s not necessarily because it's the best city for collectors but because I'm a huge K-culture enthusiast. I spend most of my summers there and I’ve spent the past five years learning Korean [she also speaks French, German and Spanish].

A visitor in front of works by Doofan Kwaghhool at the Un-Told exhibition at Retro Africa in 2020 Courtesy of Retro Africa

How has Covid-19 effected your business in Nigeria?

The pandemic has increased the number of sales inquiries by maybe four times. Many people are buying online, which is good for galleries that are not based in metropolitan cities in the West. They are searching for different things and are more likely to discover galleries like mine. So Covid has been a curse and a blessing in that our international collector base has increased; however, it has reduced the amount of shows we would normally hold. While the Covid case numbers in Nigeria have not been extremely high, we would like to keep it that way, so there have been periodic restrictions that have limited activity.

So would you say that you've sold more art in the past year than ever before?

Yes, definitely.

You’re also working on some national art projects in Nigeria?

I am working on creating an Institute of Contemporary African Art and Film (ICAAF) in Ilorin, Nigeria. It is going to be the first institution of its kind in the country and the only purpose built museum for contemporary art. It will have gallery spaces for a collection of African art, studio spaces for artists, and post-production facilities for film. One of the other cultural strengths we have in Nigeria is Nollywood, the nickname for our film industry, which is widely consumed in Africa and is ever-expanding. My sister is the architect on the project so it’s great to be working together again. The space is due to open in September 2022.