On the surface, there might seem to be little in common between computer code and visual art, but both are at the centre of major copyright cases in US courts. In fact, a recent US Supreme Court decision in a lawsuit between technology giant Google and the software company Oracle is now being cited in an ongoing case between the celebrity photographer Lynn Goldsmith and the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

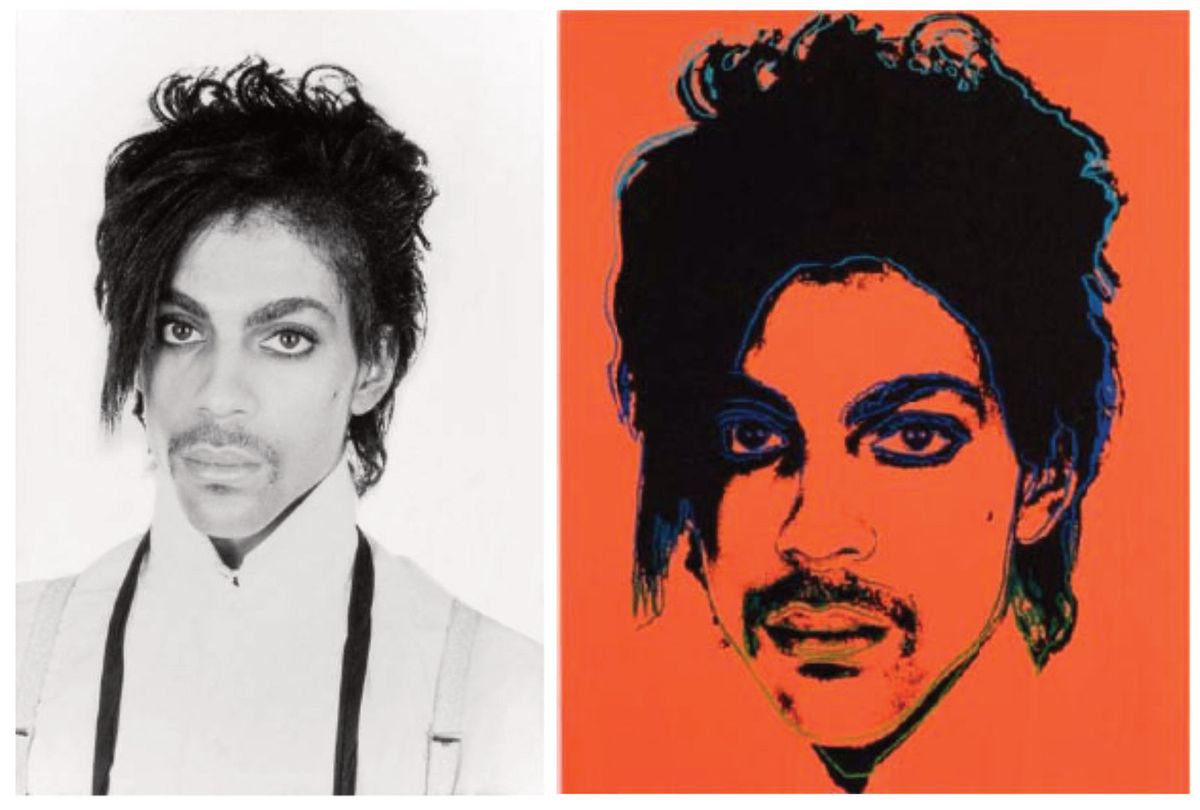

Goldsmith says the Supreme Court’s ruling in April that Google had not infringed Oracle’s copyright, even though it directly copied 11,500 lines of software code, is “fully consistent” with the New York Second Circuit federal appeals court ruling the month before which said Warhol did infringe Goldsmith’s copyright when he used her 1981 portrait of the musician Prince as the basis for a series of silkscreens. The Supreme Court, Goldsmith says, “applied the same, case-specific fair use principles” that the New York court did, including the “transformative-use test”.

Failing the test

In opposition, the Warhol foundation is claiming that the Google decision urgently requires the New York court to rehear its case. A lower court had decided in its favour, finding Warhol’s images sufficiently “transformative”. But the Second Circuit three-judge panel court said they were not, reversing the lower court’s decision on appeal and ruling that Warhol’s 16 silkscreen prints and pencil illustrations failed the four-pronged fair use test. Under copyright law, whether the appropriation of another artist’s material is fair use depends on certain criteria: the purpose and character of the use, the nature of the copyrighted work, the proportion and substantiality of the original used, and the effect on the market or value of the original. When it viewed Goldsmith’s and Warhol’s works “side-by-side”, the Second Circuit court found that Warhol’s works were not “transformative” under the “purpose and character” test, and that “all four factors favor Goldsmith”.

More broadly, the Second Circuit decision made waves in saying that clarification was needed for its own controversial fair use opinion in an earlier case, which involved the artist Richard Prince and the photographer Patrick Cariou. In that case, the Second Circuit court said in 2013 that while a secondary work does not need to comment on a copyrighted original to be transformative, it must have a different purpose or message. But the Warhol decision reined this in, saying that an artist who seeks to use copyrighted material fairly must do more than merely impose a new “style”.

“Whether a work is transformative cannot turn merely on the stated or perceived intent of the artist or the meaning or impression that a critic—or for that matter, a judge—draws from the work,” the court ruled. Otherwise, “the law may well recognise any alteration as transformative.”

Far-reaching consequences

In its new petition for a rehearing, the Warhol Foundation says the Second Circuit decision conflicts with precedent set by the Supreme Court and other circuits, and “is irreconcilable” with the Google decision. The ruling against Warhol will have “far-reaching consequences” and “threatens to render unlawful large swathes of contemporary art that incorporates and reframes copyrighted material”, the foundation says. If works like Warhol’s Prince images fail fair use, it adds, museums cannot display similar types of works, owners cannot lawfully resell them, and copyright owners may seek their impoundment and destruction.

Goldsmith counters that, as the Supreme Court observed in the Google decision, fair use “is a highly fact-specific enterprise, and specific considerations applicable to functional computer code do not translate to highly creative artistic expression”. Because both the Supreme Court and the New York courts used the same fair use analysis, Goldsmith says, the Google decision is “irrelevant” to how the New York court decided the Warhol claim, adding that the foundation is overstating the Second Circuit’s ruling.

“The fair use doctrine has for centuries been a cornerstone of creativity in our culture,” says Andrew Gass, a lawyer for the Warhol Foundation. “Our goal in this petition is to preserve the breadth of protection it affords for all—from the Andy Warhols of the world, to those just embarking on their own process of exploration and innovation. Goldsmith’s lawyers declined to comment.”

Meanwhile, the Second Circuit court issued another fair use decision in a dispute between the photographer Lawrence Marano and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, this time ruling against the original artist. Applying the four-pronged test, it concluded that the Met had made fair use of Marano’s picture of the musician Eddie Van Halen playing his famous “Frankenstein” guitar, in an online promotion of its 2019 exhibition Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock & Roll. The museum transformed the photograph by emphasising the guitar, rather than the musician, the court noted.