His life was cut short in Italy at age 28, the result of complications from surgery after an artistic career that lasted only eight years. But more than five decades after his death, Bob Thompson’s enigmatic vision continues to resonate for artists and art historians.

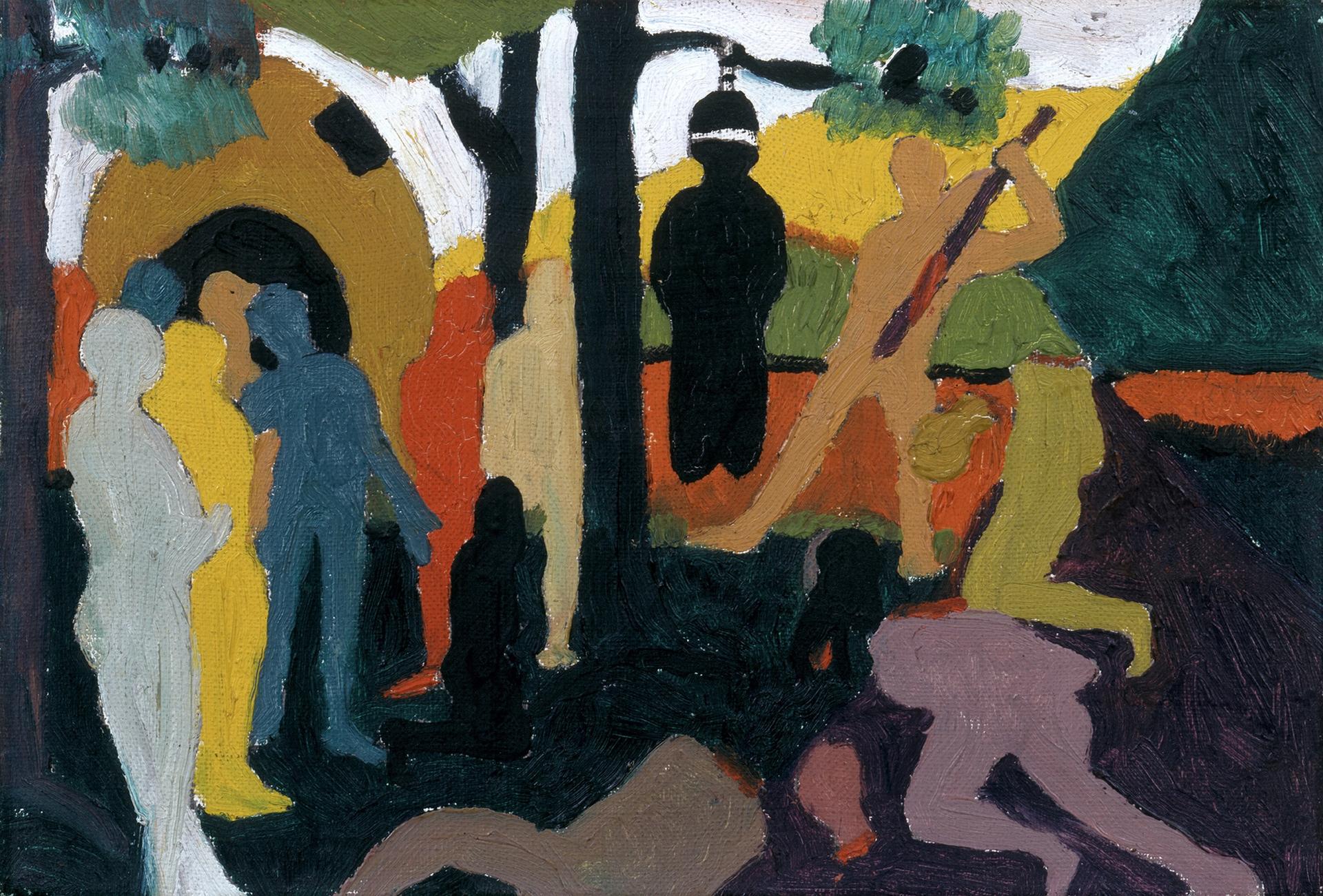

As a Black artist creating at the height of the civil rights movement, Thompson had wrestled early on with expectations that he chronicle the daily African-American experience in his paintings. But he resisted being pigeonholed, choosing instead to harness and challenge art history–above all, canonical European paintings–as a departure point for vivid Expressionist compositions that sometimes indeed evoke racial anxiety.

His work, often populated by relatively featureless human and animal figures in wooded landscapes, can also be seen as a defiant rejoinder to the pure abstraction that was dominant in New York art circles at the time.

Bob Thompson: This House Is Mine, a major survey opening on 20 July at the Colby College Museum of Art in Maine, will delve deeply into the artist’s vision while teasing out the ramifications for contemporary practice. The first sweeping exploration of his career since a 1998 retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, it presents around 85 paintings and works on paper from more than 20 institutions and 25 private collections, including five donated to the Colby museum by the Alex Katz Foundation. The show will travel to Chicago, Atlanta and Los Angeles and is accompanied by a probing scholarly catalogue.

Visitors can puzzle over Thompson’s provocative artistic responses to such masters as Piero della Francesca, Lucas Cranach the Elder, Tintoretto, Goya and Poussin; relive the creative ferment of the late 1950s and 1960s, including the Greenwich Village jazz scene and the heady adventures of expatriate Black American artists and poets in Europe; and ponder how the artist might have evolved had he not succumbed to illness at an early stage in his career.

“It’s too heartbreaking, in a way,” says Diana Tuite, the curator of Modern and contemporary art at the Colby museum who organised the show, referring to Thompson’s 1966 death in Rome. “There’s something premonitory in a way: there’s kind of a darkness in his work, a sense of mortality that is very present.”

Born in Louisville, Kentucky in 1937, Thompson was raised in a nurturing middle-class family that later moved to Elizabethtown, also in Kentucky. His father died in a car accident when he was 13, and he moved back to Louisville to live with his sister and her husband, an artist who worked as a cartographer and encouraged the boy’s forays into painting.

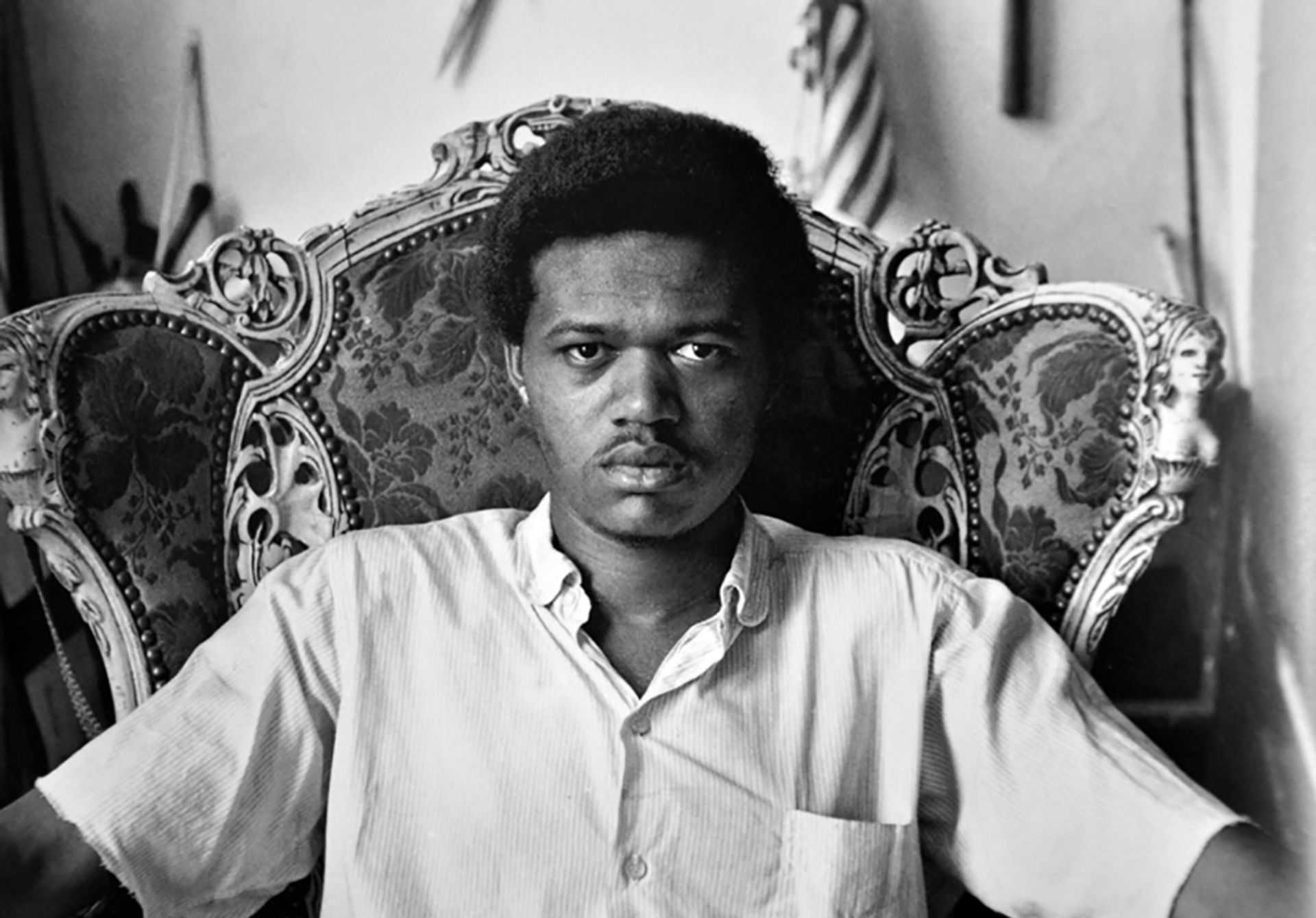

The artist Bob Thompson in 1964 Charles Rotmil

He eventually enrolled in pre-med studies at Boston University but gave that up to study painting at Louisville University, graduating in 1957. While enrolled there, Thompson began copying work by Italian Renaissance masters, an exercise that helped plant the seeds for the challenges to canonical works that he would pose as an expatriate in Europe.

A summer sojourn in 1958 in Provincetown, where he took additional art classes, proved to be a turning point: he became exposed to the work of the figurative Expressionist Jan Müller (1922-1958), who had fled Germany in the 1930s and settled in New York. Thompson never met him–Müller died earlier that year–but he drew inspiration from the émigré’s paintings, as well as a bit of advice offered by Müller’s widow, Dody: “Don't ever look for your solutions from contemporaries—look at Old Masters.”

Thompson was so compelled by Müller’s art that he painted an imaginary re-creation of a service he never attended: The Funeral of Jan Müller from 1958, on view near the entrance to the show. Unlike the majority of Thompson’s works, it is executed in somber hues. “It feels like a manifesto painting of sorts: he seems to be grieving for someone he hoped to learn from,” says Tuite. “With its dark palette, you think of Courbet’s A Burial at Ornans.” In subsequent years Thompson would embrace some of Müller’s epic historical subjects.

Bob Thompson, the Funeral of Jan Müller (1958) Minneapolis Institute of Art

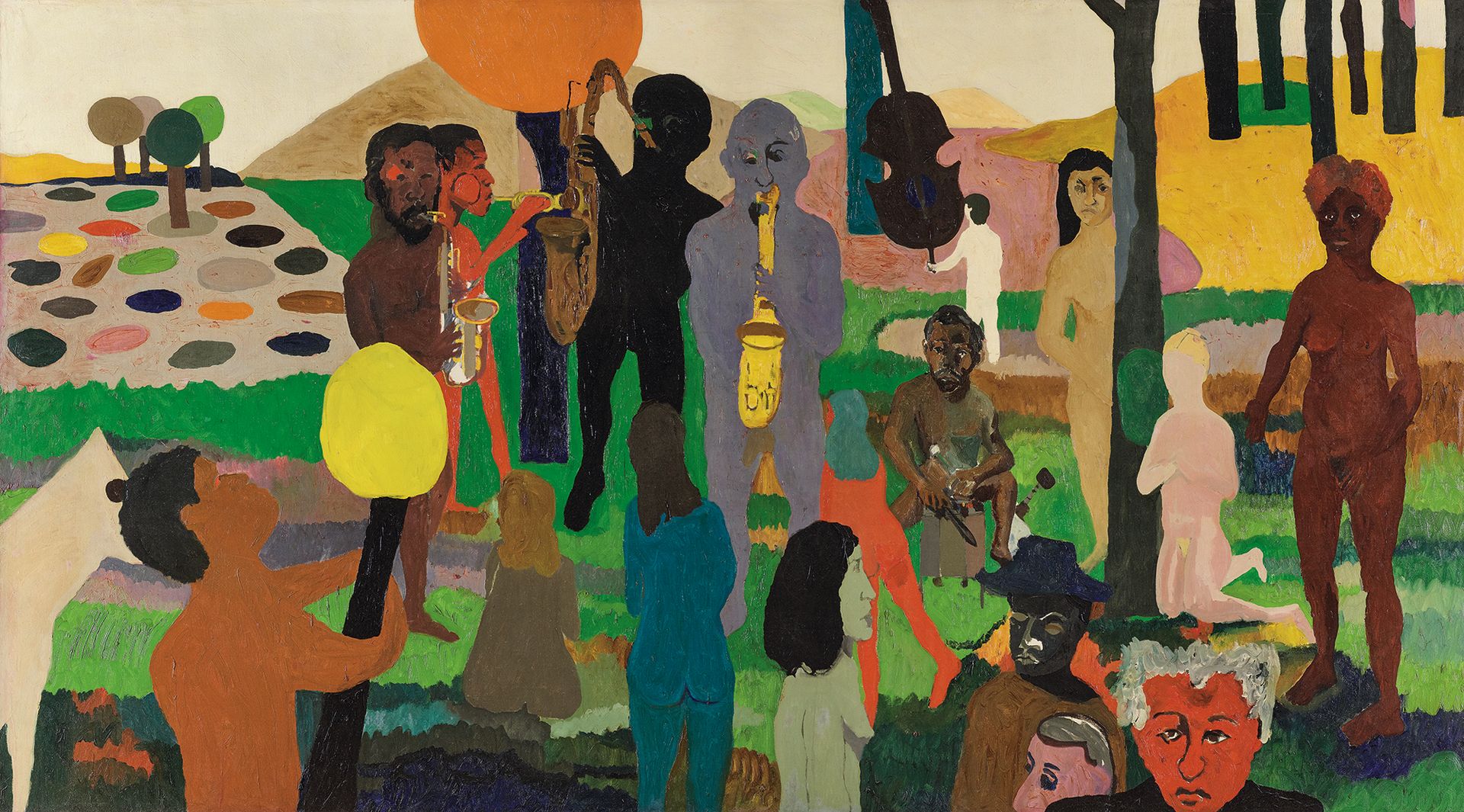

By 1959 the artist had settled in New York, where he befriended other artists, took part in Happenings organised by Allan Kaprow and became a denizen of Greenwich Village jazz haunts including the Five Spot Café. He cemented close friendships with jazz musicians and sometimes painted them: Thompson’s Garden of Music from 1960 depicts the music legends Ornette Coleman, Don Cherry, John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, Ed Blackwell and Charlie Haden with their instruments in a landscape of coloured dots and trees. “He and Ornette were particularly friendly,” says Tuite.

Bob Thompson, Garden of Music (1960) © Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York; photo: Allen Phillips/Wadsworth Atheneum

Thompson is remembered as vivacious and magnetic, an artist who was determined to succeed but was uncommonly generous and often looked out for others: “There’s a story about the artist Benny Andrews, who says that Thompson was always willing to give him any money he could,” the curator notes. Frequently, artists, poets and musicians gathered in Thompson’s studio on Rivington Street on the Lower East Side of Manhattan.

Also dating from 1960 is the diminutive This House Is Mine, an unusual proclamatory and self-referential title from which the show takes its name. In the catalogue, Tuite writes that it amounts to a “speech act”: “an explosive pronouncement of ownership” that evokes the writings of the writer James Baldwin. She noted in the interview that after he moved to France in the late 1940s and began communicating daily in French, Baldwin wrote about rediscovering English as a “language that he needed to take control of” –“a gesture of possession after dispossession” as a Black man. (The two men never met, however.)

Bob Thompson, This House Is Mine (1960) © Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York; Photo: Elon Schoenholz

“Reading Thompson and Baldwin together makes a lot of sense,” Tuite adds. The title has also been read to suggest Thompson’s ambition to forge a new visual language: This House Is Mine depicts his customarily mysterious human figures and is relatively inscrutable.

The artist was featured in his first solo exhibition in New York in 1960 and, over the next few years, his works started entering important Modern and contemporary collections. But in 1961 Thompson extracted himself from the American bohemian scene and made his first trip to Europe, exploring London and Paris with his wife, Carol Plenda Thompson, and later settling with her in Ibiza in Spain. His European museum forays and research led to one of his biggest breakthroughs: interrogating iconic works.

The Blue Madonna from 1961, with sinuously wrapped trees and the Virgin and Child at right, bears the imprint of the French Fauvist Maurice Denis. An untitled canvas from 1962 echoes Goya’s Hasta la muerte (Until death), a commentary on female vanity in the face of waning beauty from the Spanish master’s print series Los Caprichos. (Tuite says the museum has digitised Los Caprichos and installed the images on an iPad for visitors so they can make a comparison.) “Goya is such a great figure for him to model himself after because he’s such a renegade,” Tuite says. “He’s devouring Goya, which seems appropriate.”

From left, Francisco Goya, Hasta la muerte, from Los Caprichos (1799); Bob Thompson, untitled (1962) (for Thompson work) © Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York; photo: Peter Siegel, Pillar Digital Imaging LLC

The 1963 oil The Circus confronts Goya’s celebrated print El sueño de la razón produce monstruos (“The sleep of reason produces monsters”). In Thompson’s painting, two doubled-over figures clash with avian forms, although his composition suggests that the aggression may have been initiated by the humans.

From left, Francisco Goya, El sueño de la razón produce monstruos (1799); Bob Thompson, The Circus (1963) (for Thompson work) © Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York

“Really, the things that he omits and deforms and distorts interest me more than the things he’s faithful to,” says Tuite. “At first glance, they feel very familiar, but then there’s so much to closely look at.”

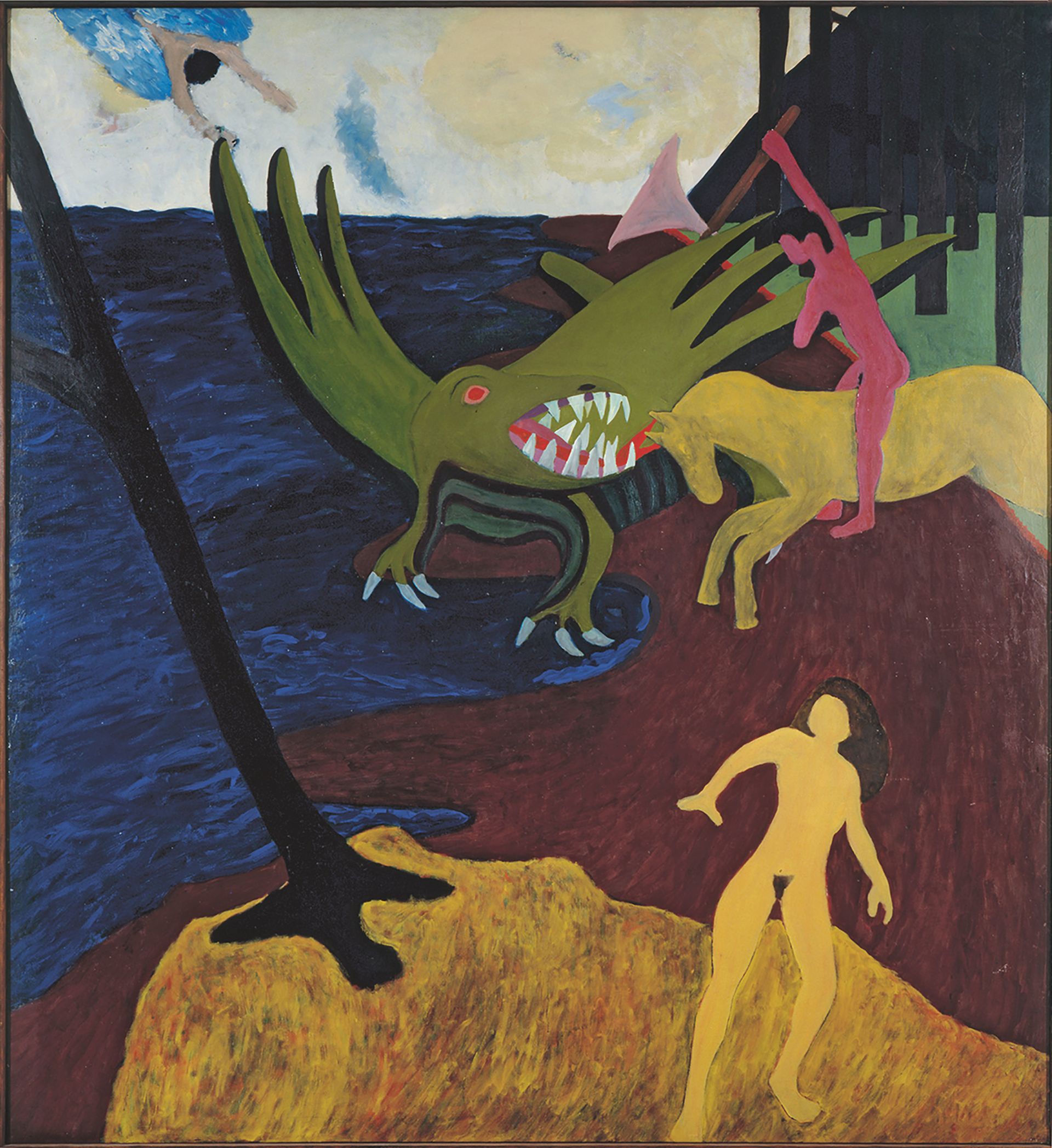

She points to St. George and the Dragon from around 1961-62, inspired by a painting from around 1555 by Tintoretto. “Tintoretto’s version is about faith, a vision of God, clouds in the sky parting and how St. George saved this village from this terrorising dragon and rescues a princess–the clouds are brightening, and God is there,” says Tuite.

But Thompson pares the composition down and triangulates St. George and the woman: “he exposes the shallow sexual politics of that myth, which reads like the id of man,” the curator says. “He’s always taking a close look at things we accept in art historical representations.”

Bob Thompson, St. George and the Dragon (around 1961-62) Collection of the Newark Museum

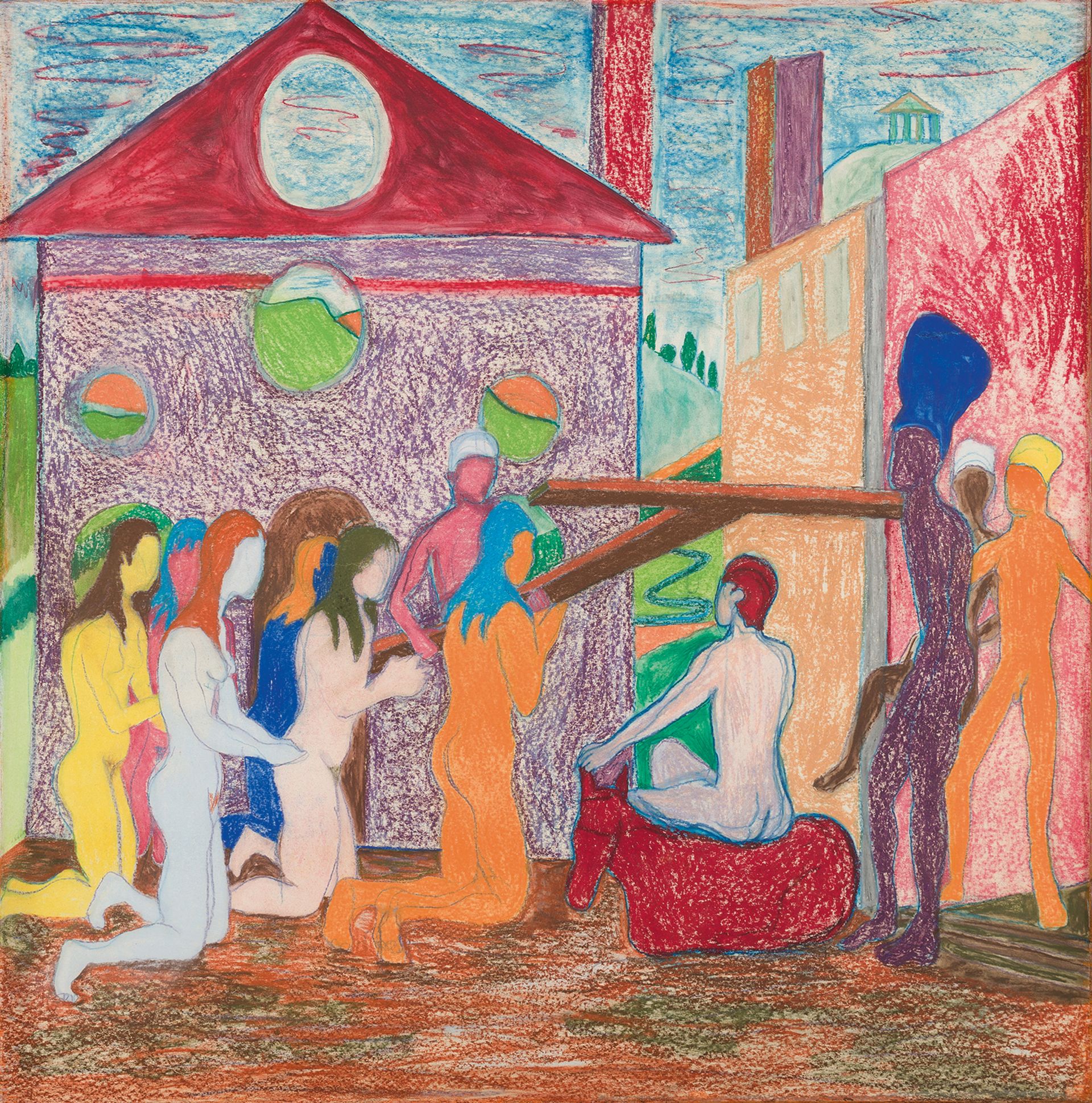

Settling in Rome during his second trip to Europe in 1965-66, not long before he died, Thompson zeroed in on Piero della Francesca’s 15th-century fresco cycle The Legend of the True Cross, a Renaissance masterpiece painted in a basilica in Arezzo. Thompson’s Discovery of the True Cross from 1966 evocatively reimagines one of Piero’s frescoes in a mixed-media work on paper mounted on canvas, substituting naked figures for the penitent humans while using a coloured pencil to invoke the luminosity of the original work.

Piero della Francesca, Discovery and Proof of the True Cross, from The Legend of the True Cross Cycle (1452–66)

Bob Thompson, Discovery of the True Cross (1966) Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York; photo: Tim Thayer

Although Thompson skirted pressure to chronicle the daily experience of Black life in America, racial themes are omnipresent in his work, Tuite says, perhaps most evocatively in images of the tree and the Crucifixion. Both Black and white artists were using such imagery to allude to lynchings of Black Americans in the South, she notes. Thompson’s nightmarish The Hanging from 1959 depicts menacing figures and a dangling body; in The Execution from 1961, a hanging corpse surrounded by faceless humans wears a blindfold.

Bob Thompson, The Hanging (1959) Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia

Bob Thompson, The Execution (1961) Courtesy of Ellen Phelan and Joel Shapiro

In Untitled (The Tree Lift) from 1962, meanwhile, with a cartoonish Jesus with an inflicted wound, “there’s something haunting in the figuration,” Tuite observes.

Bob Thompson, Untitled (Tree Lift) from 1962 Courtesy of the California African American Museum Collection of Friends, the Foundation of the California African American Museum

The curator is confident that the exhibition will pave for the way for future research, including a deeper examination of how other Black American artists used canonical works to carve out their own styles and pose provocative questions, from Romare Bearden in the 1950s to Robert Colescott in the 1970s and 1980s.“There’s a lot more to be done with that, particularly in terms of violence” against Black Americans, Tuite says,

In an essay in the show’s catalogue titled A Tale of Two Bobs, the art historian Lowery Stokes Sims notes that while Thompson used colour to “effectively upend the staid orderly precepts of Renaissance and Baroque narratives with Expressionist irreverence", Colescott deployed gaudy hues “to strip masterpieces of their weathered and varnished respectability”. Both artists "were able to pay homage to that art history while indicting it for its lapses,” she adds.

The exhibition is meanwhile inflected by the protests against racial injustice that swept the US after George Floyd’s killing by the Minneapolis police in May 2020, although planning for the show was far along by then. It also implicitly interrogates Thompson's obscurity. Over the years, “giving tours of the museum to curators and art historians, I realised how unknown Thompson was,” Tuite says. And with a racial reckoning unfolding, “we feel like the audience could receive this in a new way.”

Bob Thompson: This House Is Mine, Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine, 20 July–9 January 2022; Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago, 10 February 2022–15 May 2022; High Museum of Art, Atlanta, 18 June 2022–11 September 2022; Hammer Museum, University of California, Los Angeles, 9 October 2022–8 January 2023.