In April, Christie’s sold the Ionides Scarab, a sixth-century BC “archaic Greek masterpiece”, for $250,000 in New York. But it may not have been Christie’s, nor the consigner’s, right to sell the object in the US.

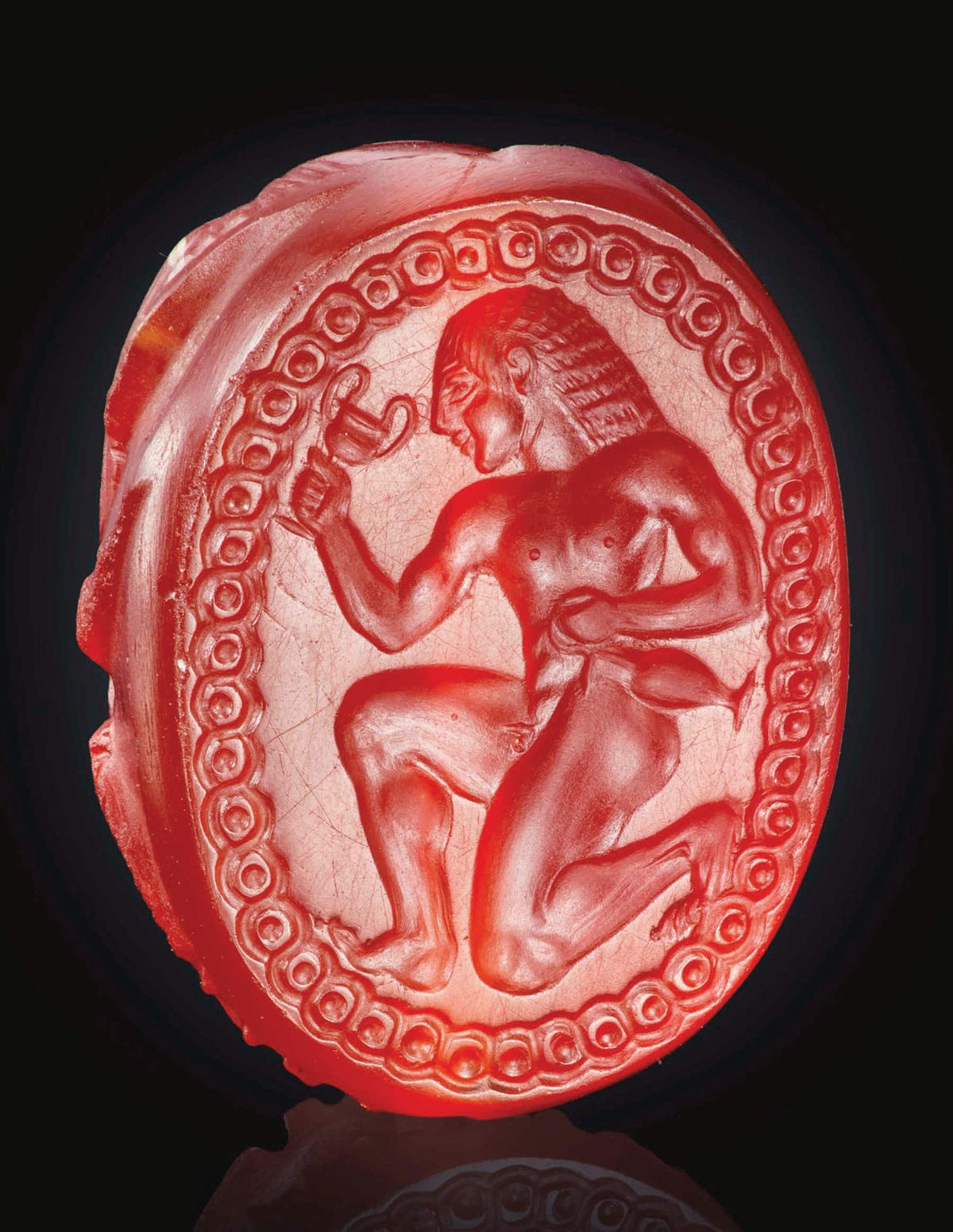

In 1983, Thomas Heneage, the London-based bookseller and a specialist in engraved gems, sold the intaglio—a cornelian sealstone, shaped like a scarab, engraved with a running youth—to a US collector for £71,380 (nearly £250,000 today), one of the highest prices ever paid for a gem.

However, according to the published record of the sale seen by The Art Newspaper, the UK’s Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art and Objects of Cultural Interest denied the seller an export licence for at least ten years or until “fresh material factors had emerged”. The Export Reviewing Committee advises the UK government on whether a cultural object intended for export is a national treasure, in which case it is stopped to ensure it is kept in the UK. According to the scarab’s provenance on Christie’s website, the gem came into the hands of the New York collector “by 1986”—before the end of the ten-year period. How did it get to New York, and what “material factors” came to light between 1983 and 1986?

Heneage declined to comment, on the advice of the UK’s HMRC tax authority, because the scarab is part of an investigation by HMRC and the US’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement. HMRC could “neither confirm nor deny any investigations” and ICE did not respond to a request for comment. When a Christie’s spokesperson was asked if the auction house was aware the scarab was possibly sold without an export licence, they chose to “refrain from commenting”. Arts Council England, which oversees the UK’s Export Reviewing Committee, declined to locate any reports concerning the scarab, stating that it is unable to answer questions directly.

According to Alexander Herman, the assistant director of the Institute of Art and Law in the UK, a permanent export stop would normally only be placed on an item if the owner rejected an offer from a UK institution. In fact, the Reviewing Committee document shows that a representative of the buyer said the scarab had been on the market since the 1970s with no interest from UK institutions, many of which had multiple archaic Greek gems in their collections, including the British Museum, the Ashmolean and the Fitzwilliam, and at the time no offer had been made.

The committee said the gem was worthy of being kept in the UK because it fulfilled the second and third of its three Waverley Criteria—namely that it is of outstanding aesthetic importance and significance for the study of art history—and hoped that a UK institution would make an offer. Interestingly, the owner seems to have told the committee that they would not accept such an offer, which led it to deny the export licence for “a considerable period, perhaps ten years”.

So, how did a gem that was never supposed to leave the UK end up for sale at an auction house in New York?