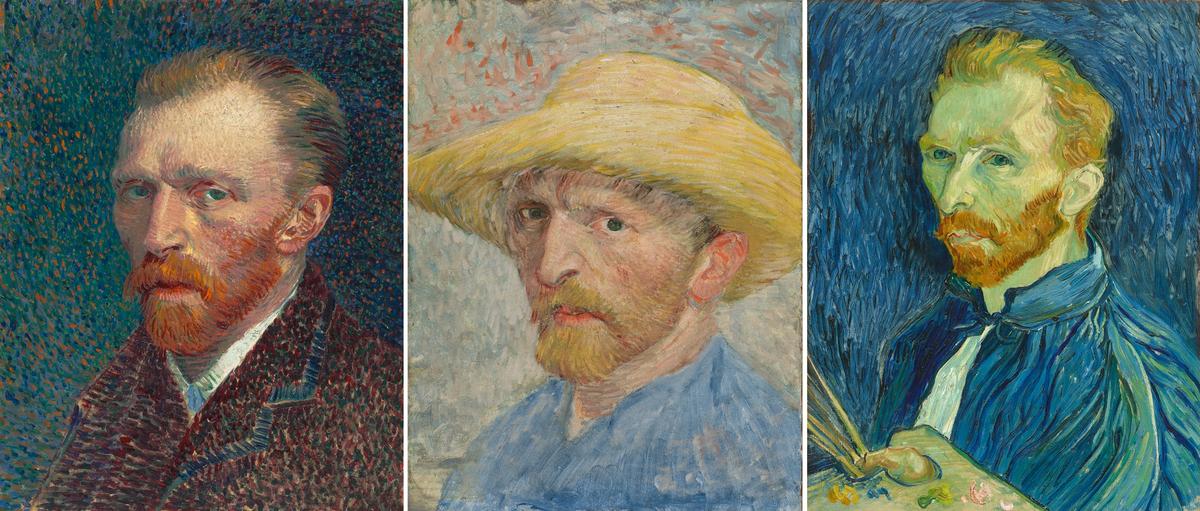

It has just been announced that London’s Courtauld Gallery is to hold an ambitious exhibition on Van Gogh’s self-portraiture next spring (3 February-8 May 2022). Curated by the Courtauld’s curator Karen Serres, Van Gogh Self-Portraits will be the first show ever to cover the full chronological range, reassembling nearly half of his self-portrait works. I am writing an essay for the catalogue.

Few artists have produced as many self-portraits as Van Gogh. Among Vincent’s great predecessors, only his fellow Dutchman Rembrandt painted slightly more, and that was during a career lasting more than four times longer (with just over 40 paintings, compared with Van Gogh’s 35). As with Rembrandt, our view of Van Gogh’s appearance is almost entirely conditioned by the self-portraits. Only a single photograph of Vincent’s face survives, taken when he was 19.

When we look at Van Gogh’s self-portraits, so often we are hoping to get an insight into his personality and thoughts. This is because most of us are as fascinated by his extraordinary life as his amazing art.

Vincent felt that portraiture (and presumably self-portraiture) could do what photography had failed to achieve. He disliked what was then a fairly recent technological development, which presumably explains why we have no photographs of him as an adult.

As Vincent told his sister Wil: “I myself still find photographs frightful and don’t like to have any, especially not of people whom I know and love.” On another occasion he told her that “it isn’t easy to paint oneself”, but “one seeks a deeper likeness than that of the photographer”.

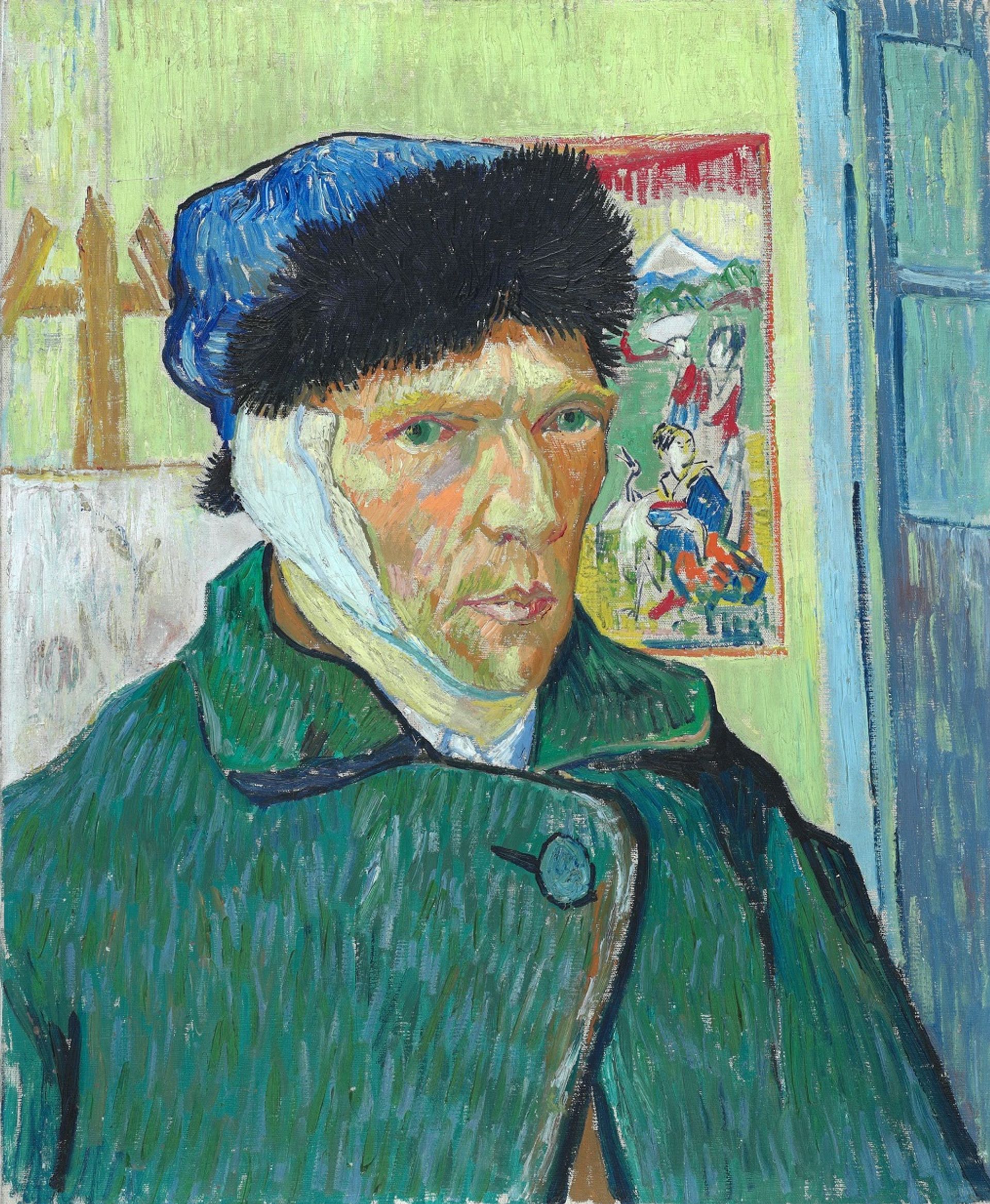

Van Gogh’s Self-portrait with Bandaged Ear (January 1889) © The Courtauld, London (Samuel Courtauld Trust)

In some paintings, such as the Courtauld’s Self-portrait with Bandaged Ear (the centrepiece of the coming exhibition), the artist is probing his inner self and presenting a facet of his life. Painted just under a month after he mutilated his ear, he does not shy away from the trauma he had suffered. He could have depicted the other side of his head or made the bandage appear less prominent.

Instead the artist presents a highly confrontational image. Its precise meaning must have been clear to Vincent, but it remains elusive for us today. Is it a cry for help? Or does it represent his determination to get back to work? Perhaps it is both.

Vincent includes his easel, on which he has placed an almost blank canvas (there are some vague marks on it, most likely the beginning of a flower still life). And on the other side of his head hangs a Japanese print (one which he had with him in the Yellow House in Arles). This represents an homage to the art of Japan, which was such an inspiration for him.

Despite Vincent’s fragile health, the Courtauld self-portrait is a very carefully composed image, certainly not the impulsive work of a “madman”. He shows the bandage on what appears to be his right side, although it was his left ear which he cut. Since he was looking at himself in a mirror, the sides are reversed in the painting. A detail which is often missed: the jacket was also observed in the mirror, so the button (which for a man is conventionally on the right side) appears to be on the left side in the Courtauld painting.

In Self-portrait as a Painter (February 1888), the last of his self-portraits done in Paris, Van Gogh advertises the skills that he had acquired during his two years in the French capital—and particularly his use of colour (the ginger hair contrasts with the complementary blue clothing). This time he meticulously went to the extra trouble of putting the button on the correct side, not as he would have seen it in his mirror.

Van Gogh’s Self-portrait as a Painter (February 1888) Courtesy of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

On other occasions Van Gogh painted self-portraits because of a lack of models. He always found it difficult to get people to sit for him, probably a reflection of his awkward personality. Van Gogh also seems to have had a general aversion to painting close friends and family. Without models, the simplest way to develop as a portrait artist is to paint oneself, since this only requires the use of a mirror.

From the asylum, in September 1889 (when he painted the self-portrait now in Washington, DC, which will be coming to the exhibition), he wrote to Theo: “I’m working on two portraits of myself at the moment—for want of another model—because it’s more than time that I did a bit of figure work.”

On other occasions he made self-portraits to try out various technical explorations, such as colour contrasts or brushwork. These less ambitious works were sometimes more in the way of studies. This helps to explain why 27 of the 35 self-portraits date from his Paris period, when he was experimenting and developing his technique—moving away from the dark hues of his Dutch years to the Van Gogh we now know and love, with his exuberant colouring. But the Paris self-portraits also include some very fine examples.

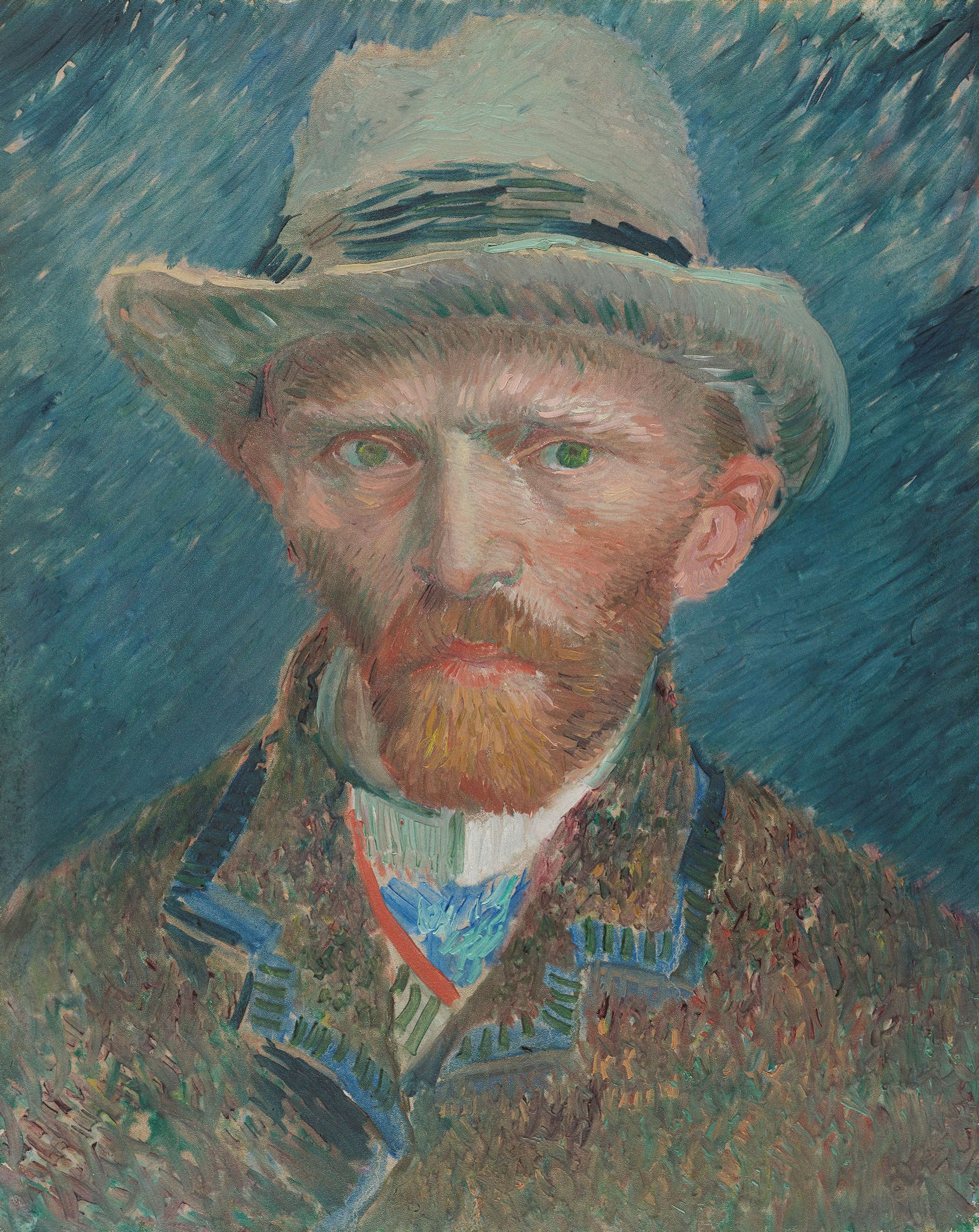

Van Gogh’s Self-portrait with grey felt Hat (1887) Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In 1889, while at the asylum, Vincent wrote in a letter to Theo: “It’s difficult to know oneself – but it’s not easy to paint oneself either.” He persevered with the challenge, pointing out that photographs become “faded more quickly than we ourselves”, while paintings remain “for many generations”.

Other Van Gogh news

“Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence”, published in paperback this week Courtesy of Frances Lincoln/Quarto

My book Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence is out in paperback this week. First published in 2016 by Frances Lincoln, it deals with the artist’s 15 months in Arles, where he produced his greatest work. The book, with considerable fresh material, includes his collaboration with Gauguin in the Yellow House, which ended so disastrously with Vincent’s mutilation of his ear.