Amid the pandemic last year, Italy quietly relaxed its famously stringent art export laws to allow the export of some, lower value Old Masters—in theory at least.

Previously, under the Italian Cultural Heritage Code, older works of art (regardless of value) needed an export licence to leave the country. Applications were frequently refused, stifling Italy’s non-contemporary art and antiques trade in the process. Only works by living artists or those by artists who died less than 50 years ago were allowed to be freely exported, without a licence.

However, in 2017, a reform (the Ministerial Decree no. 367) extended the deceased artist clause to 70 years and brought in a value threshold of €13,500, below which art and antiques could be exported without a licence. This decree was finally approved last July and came into force on 22 September 2020.

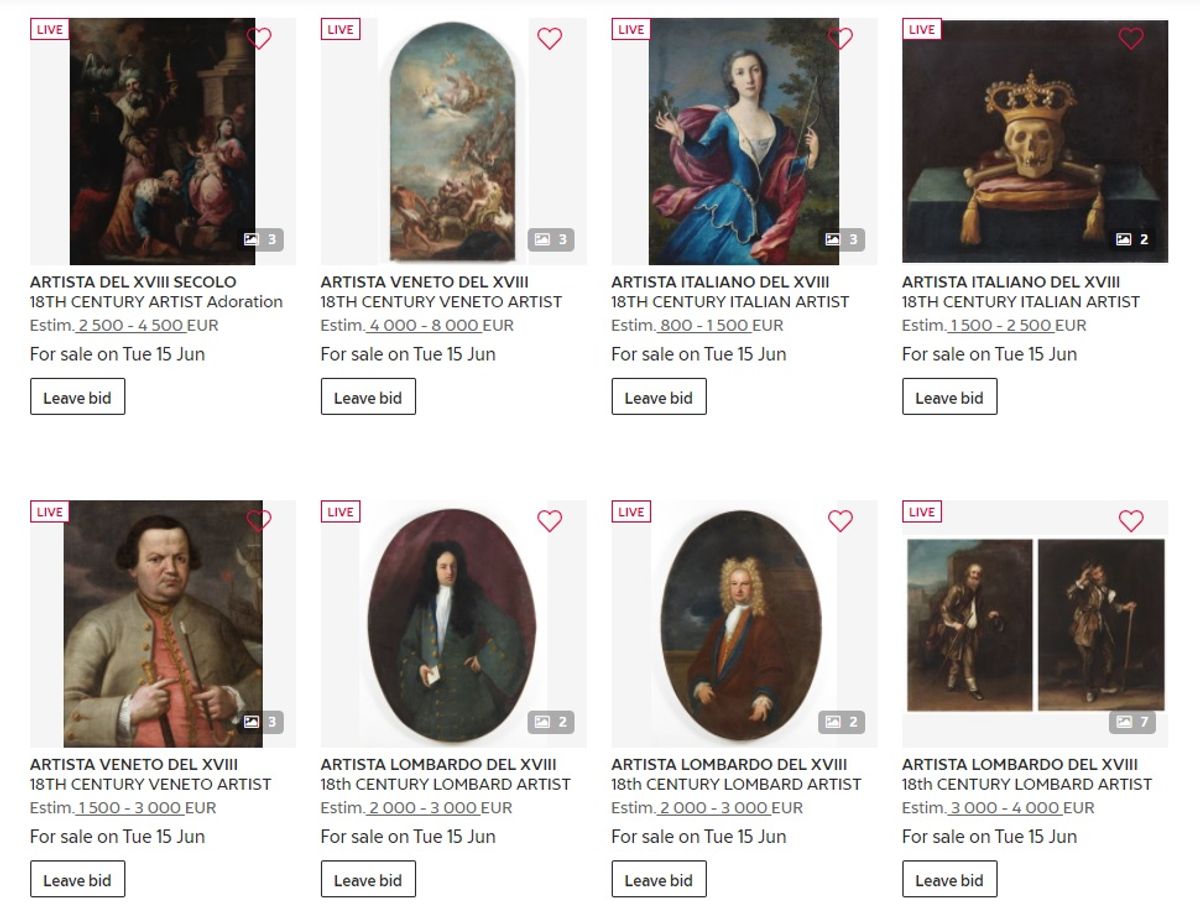

As a result, some Italian auction houses, including Finarte, Bertolami, Cambi and Capitolium art, have started listing lower value items on online bidding marketplaces, such as DrouotOnline.com.

But it’s taking a while for the wider trade to take note of the changes, says Antoine de Rochefort, the chief executive of Drouot Digital: “Information about the decree was scarce outside Italy and, after nine months, we have seen no change in terms of the average price of lots auctioned to internet bidders. The average price per lot purchased in Italy is still around €1,300. I expect the market will catch up. But just now, there is quite an opportunity for bargain hunters.”

Not everyone thinks the new laws will make much difference. Giovanni Sarti, the Paris-based, Italian Old Master dealer, says he was against the proposed changes from a cultural heritage perspective when they were first suggested in 2017 and he thinks it might encourage people to deliberately undervalue works that they are trying to export, so they fall under the €13,500 threshold. "My colleagues in Italy were pleased at first, but now they tell me it has made life more difficult, because the Italian superintendents [who oversee export licence applications] are looking at things more closely," Sarti says. "You still have to send a photo of the painting to the superintendent, but now it takes longer to get an export licence as they are having to try to determine the value of the painting—it's a lot of extra work for them."

How will the value of works of art in question be determined? And what documents with they need if self-certified? The art lawyer and university professor Francesco Emanuele Salamone explains the new process in a comment piece for The Art Newspaper’s sister publication, Il Giornale Dell’Arte.

Here is what you need to know, in practical terms:

- In the case of goods purchased in the last three years at auction or from an art dealer, it will be sufficient to produce the invoice showing that the hammer/sale price of the works of art—net of commissions and charges (such as, for example, insurance or transport costs)—does not exceed €13,500.

- In the event of a transfer between private individuals in the last three years, it will be sufficient to attach a copy of the contract signed by the parties or, alternatively, a joint declaration before an official authorised to receive it, declaring that the sale of the asset took place at a price not exceeding the threshold of €13,500

- In the case of an attempted sale of the work at auction abroad, it will be sufficient to produce the proof (e.g. the catalogue page, the mandate to sell or the valuation from the auction house) which shows that the maximum estimate of the work does not exceed €13,500

- Finally, in the absence of a sale or attempted auction (for example, in the case of export without a change in ownership of the work of art) it will be possible for the private individual to attach the estimate of an expert registered with the register of technical consultants of a Court or physically present the goods to the Export Office for the determination of the value.