The Smithsonian Institution’s Archives for American Art has acquired a vast archive of writings and publications related to the pioneering Land Art artist Nancy Holt. The bequest, which is held in part ownership with the Holt-Smithson Foundation, includes more than 50,000 files spanning over four decades that follow the development of her art and personal life, including her work securing the legacy of her husband and fellow land artist Robert Smithson, as well as documentation of several unrealised works that the foundation hopes to bring to fruition in the future.

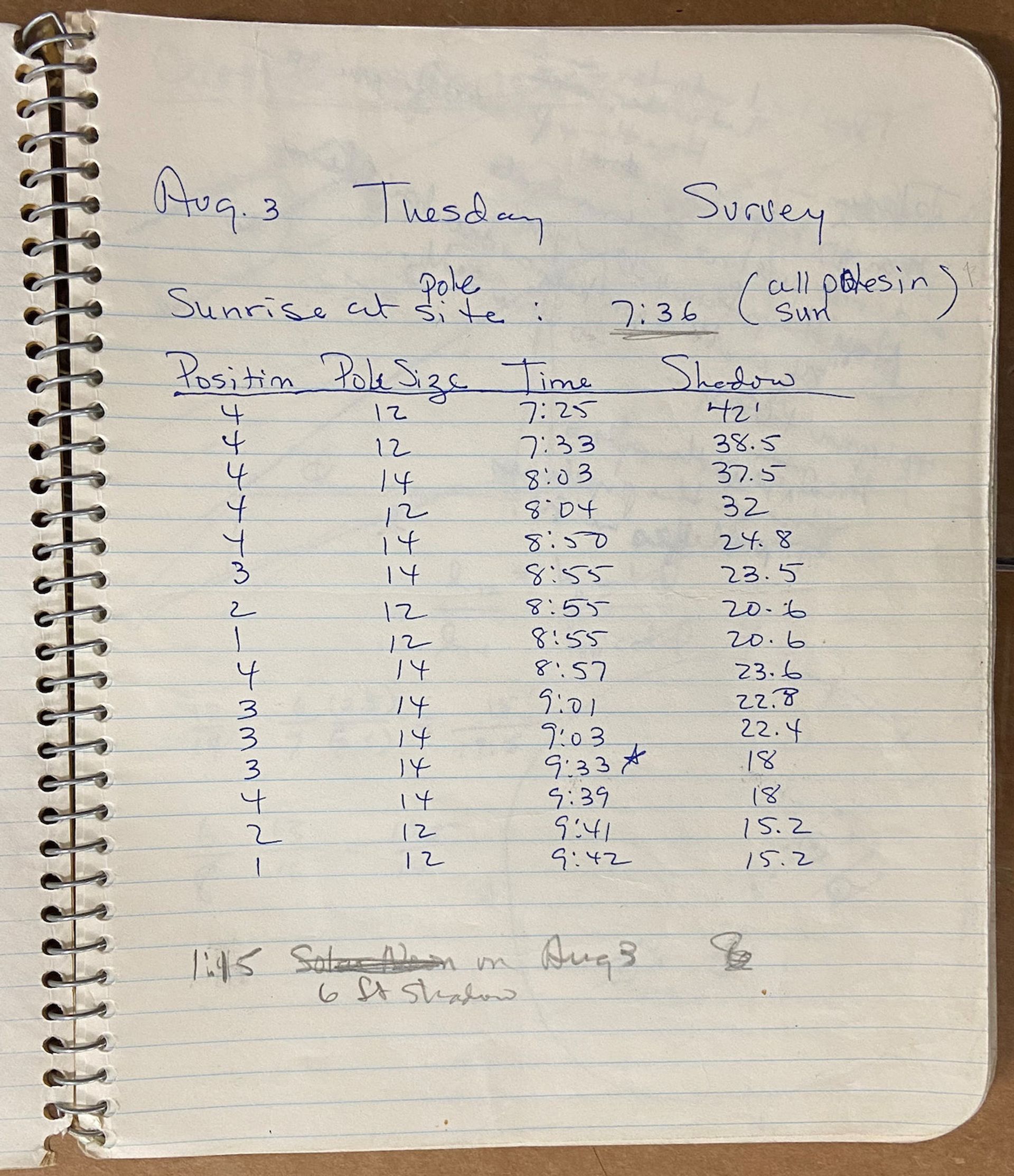

The archive reveals “how deliberate and perceptive Holt was about sight-lines, and how she was keenly attuned to one’s placement on the Earth, the passage of time and the movement of the sun”, says Liza Kirwin, the Smithsonian’s interim director of the Archives of American Art. Her notebooks from 1975 to 1976 include timed and dated observations of the effect of shadows in her design for Sun Tunnels (1976) in the Great Basin desert in Utah, while several papers detail time-based measurements of cast shadows for Dark Star (1984) in Arlington, Virginia.

An page from Nancy Holt's notebooks © Holt/Smithson Foundation

The collection, which will eventually be digitised, also includes dream journals, transcripts of interviews, photographs and even financial documents that “provide a substantive record for Holt’s interior and exterior world”, Kirwin says.

The trove also includes documentation of two projects that the Holt-Smithson Foundation still hopes to fully complete in the future, according to Lisa Le Feuvre, the organisation's director. Among them is the earthwork Sky Mound which has been on hold since 1984 and was originally envisioned to revive a landfill in the New Jersey Meadowlands just four miles outside of Manhattan, between the Amtrak rail-yards and the New Jersey Turnpike. “Holt was recruited to design the reclamation of the site and her plan was to mitigate environmental damage, transforming the landfill into a sculptural observatory and as a sanctuary for wildlife and people, a moment of calm in the sprawling and swarming urbanism,” Le Feuvre says.

The ambitious earthwork would be divided into a “solar and lunar area, incorporating paths aligned to the solstices, a large granite sphere encircled by a moat representing the moon, methane flares visible from airplanes overhead and a pond that would attract wildlife and drain surface water from the landfill”, Le Feuvre says. Until now, the pond is the only completed portion of the work.

Aerial view of Nancy Holt's Sky Mound site taken in 2006 Photo: Matthew Coolidge

Another sculpture the foundation hopes to eventually realise is Solar Web (1984-89) on Santa Monica Beach in California, an open structure that tracks the motion of the sun and is astronomically calibrated to be accurate for the next 1,000 years. “As with Holt’s landmark Sun Tunnels, a perfect alignment takes place on the summer solstice when an inverted solar eclipse appears in shadow form across the beach,” Le Feuvre says. The work was funded and approved by the California Coastal Commission and the city of Santa Monica, but after complaints from property owners that the sculpture would spoil their ocean views, a new council internally voted a second time in 1999, and by one dissenting vote decided to discontinue the installation.

The acquisition also aims to broaden research around the role of women in the Land Art movement, which has “long had a reputation as a masculine arena”, says Jacob Proctor, the Smithsonian’s Gilbert and Ann Kinney New York Collector, in charge of new acquisitions. “The depth of historical material solidifies Holt’s position as a pioneer of the movement, revealing the complex research and organisational labour involved in realising her works, while her writings, interviews and correspondences demonstrate how Land Art was as much a discursive and media practice as a sculptural one.”