The Covid crisis has created havoc, even in the sunnier climes and “bling” paradise of the south of France. In response, the main art players of the Plein Sud region have pooled resources, coming together to sustain artists and cultural offers, and to encourage visitors to explore their rich programmes of contemporary and Modern art over the summer months. The “Plein Sud” network is the brainchild of the directors of the Villa Carmignac and the Villa Noailles, Anne Racine and Jean-Pierre-Blanc respectively; Villa Carmignac nestles calmly in the midst of the picturesque island of Porquerolles, while the modernist gem, the Villa Noailles, stands high above the old French Riviera resort of Hyères, with just a 15-minute Mediterranean ferry ride dividing them.

The network brings together 66 art venues, so that—once Covid-testing hurdles have been negotiated if coming from abroad—one can “criss-cross freely through a territory bordering the Mediterranean coastline, from Sérignan to Monaco up to the foothills of the Alps”, as their free guide explains.

Some of the Plein Sud network’s venues will be familiar to the seasoned cultural tourist, such as the Fondation Maeght in Saint Paul-de-Vence or the Musée Matisse in Nice. But few will have encountered its most significant newcomer: the spectacular art campus LUMA Arles, which opened in June in the ancient city of Arles, a city best known as the place frequented by Vincent van Gogh towards the end of his life, and for its impressive Romanesque architecture and Roman amphitheatre.

Situated on the broad avenue Victor Hugo, LUMA Arles' 56-metre glittering silver tower, designed by Frank Gehry, rises out of a former railway siding, juxtaposing the gentle, sandy hues of Arlesien buildings. Best known for his Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, whose shimmering structure suggest fish scales and harmonises with the grey skies of that Basque city, Gehry—now 92—has created a building which, in the glare of the south, seems more like a fish out of water. But its 11,000 recycled stainless-steel panels are designed to reflect the light of Arles and the blues of Van Gogh’s skies, and it is tempting to compare the tower’s twisting form with the artist’s surging cypress trees. At night, with its multiple staircases and its circular drum lit from within, it looks more like Breughel’s Tower of Babel.

Tower of Babel? LUMA Arles at night Photo: © Iwan Baan for LUMA Arles, 2021

The LUMA Arles project is directed by the formidable Maja Hoffmann, the founder and president of the LUMA Foundation, whose fortune derives from the family’s Swiss pharmaceutical business, but whose vision is fired by the profound social impact that artists and creativity can have. This vision fully embraces the ecological and environmental concerns of her father, who went on to co-found the World Wildlife Fund. LUMA’s creative campus includes four 19th-century railway factories renovated by the architect Annabelle Selldorf and gardens magically conjured out of the former railway brownfield by the landscape designer Bas Smets. Navigating the exhibitions in the various industrial spaces is not unlike tackling the Arsenale space at the Venice Biennale, though much more pleasurable, due to the verdant atmosphere of the garden with its 800,000 local plants, plentiful trees and artificial lake, which runs off wastewater and creates its own cooling atmosphere.

The exhibitions themselves—both in the tower and the surrounding spaces—are impressive, though rather safe; they mostly comprise a sort of “greatest hits” of the contemporary art scene, with the obligatory Richard Long floor (from the Hoffmann family collection) and two gleaming new iterations of Carsten Höller slides. Contemporary art spaces are now at risk of having their own homogeneity—a bit like the shopping experiences in the high streets of many towns. But the works are accessible, enjoyable and emphasise the variety of the spaces, and the temporary exhibition programme will probably get more adventurous over time. There are artist residencies and a special space devoted to the Atelier LUMA, where environmental investigations are carried out and some magical products created: these include the sparkling salt crystal tiles that line the walls of Gehry’s welcoming interior, and panels made of compressed sunflower stalks that form the wall decoration of Thai artist Rirkrit Tiravanija’s elegant café with its Aubusson carpet.

Salt crystal tiles at LUMA Atelier

The most surprising experience in Arles, however, is furnished by the nearby Fondation Vincent van Gogh, which explores Van Gogh’s resonance with contemporary artists through temporary exhibitions. Also part of the Plein Sud network, it currently features the American artist Laura Owens's inspired response to seven works by Van Gogh (all on loan). Owens has produced monumental paintings on handmade wallpapers, mixing different techniques and incorporating coloured sand. The motifs in the wallpaper are borrowed from an obscure English designer Winnifred How, who worked in London in the early 20th century, and each wallpaper hosts a painting that Van Gogh made in the last years of his life. Far from being lost in the exuberant riot of pattern and colour, each Van Gogh masterpiece amazingly takes on an even greater texture and vibrancy. Van Gogh came to Arles to start a “Studio of the South” for artists, and—in parallel with this exhibition—Owens has instituted LUMA Arles’s own Studio of the South, which will host artist’s residencies.

Laura Owens and Vincent van Gogh, at the Fondation Vincent van Gogh Arles

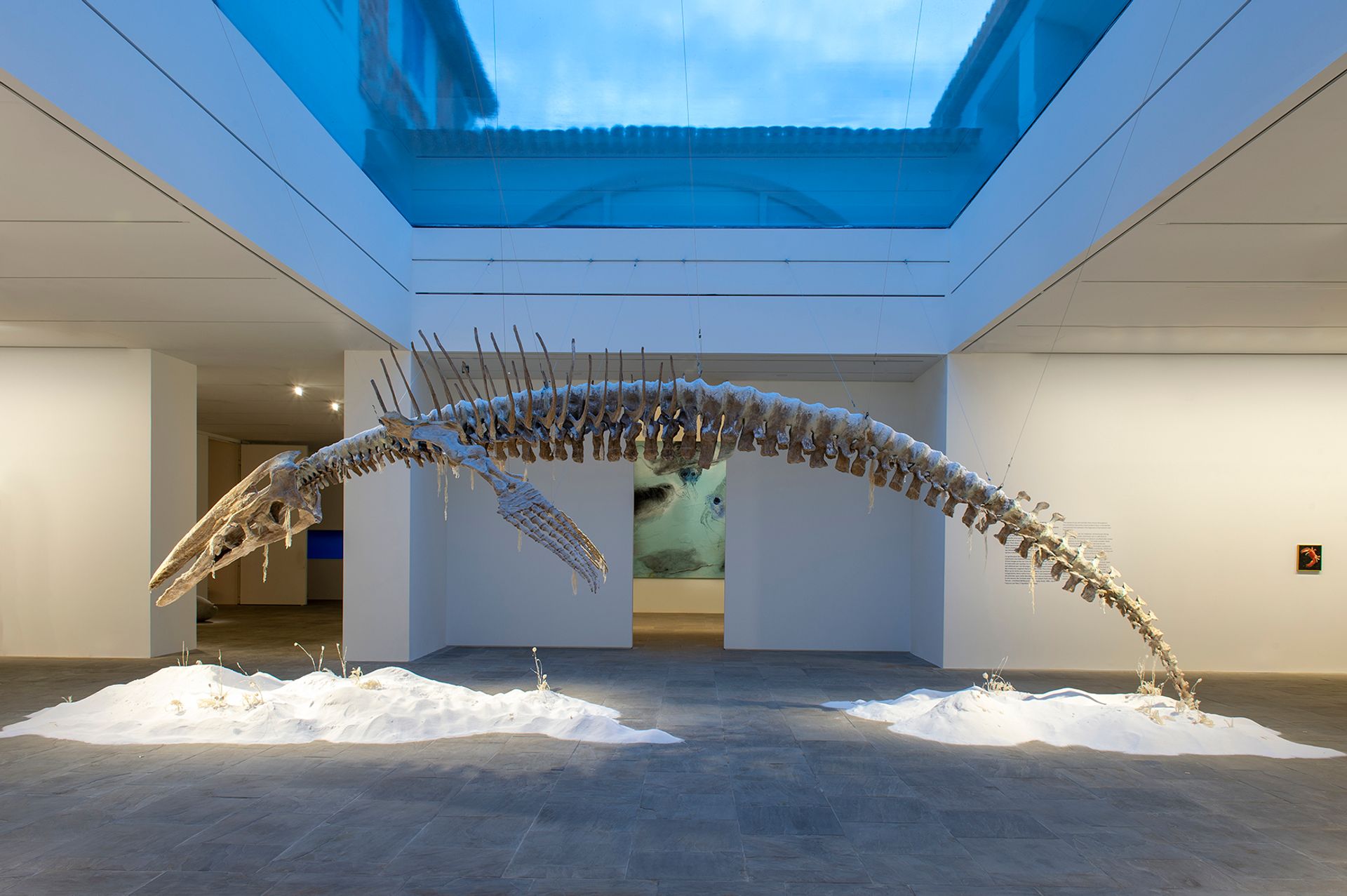

A train and a boat-ride away, the Villa Carmignac—unlike LUMA Arles—blends seamlessly into the landscape of the Iles de Porquerolles. While Hoffman and Gehry’s project turns heads and has reportedly riled some of the population of Arles (the city has some of the highest unemployment in France), the Carmignac Foundation’s main galleries, occupying 2,000 sq. m of space, had to be built underground, so as not to upset the natural environment of this national park, and the foundation has taken care to bring the island’s residents on board. The subterranean space is lit by an aquatic ceiling, with light shining and rippling through the water above.

The Foundation Carmignac, founded in 2000 by the banker Edouard Carmignac, has been run by his son Charles Carmignac since 2017. The aim of the Villa Carmignac, which opened in 2018, is to create a space dedicated to promoting art both from the foundation’s contemporary collection and in the form of major temporary exhibitions, far away from the busy centres of a town or a city. Visitors can “leave their habits and the familiar behind”, Charles says, “they can take a 15-minute boat trip and wash their mind. A clear mind can be penetrated by new visions”. In tune with its surroundings, a preserved and protected forest in the middle of the sea, the centre also includes a botanic conservatory, sculpture gardens, a seed library and aims to have “empathy and love for everything that lives”. As for the local islanders, Charles admits that at the project’s inception they had “legitimate fears, but the foundation “formed strong links and an organic relationship”. And as for the collection and the art: “My father and I have a complementary sensibility,” Charles says. “I can be really seduced by a concept, my father by sensation.”

The villa’s current exhibition The Imaginary Sea is curated by the writer Chris Sharp and seductively imagines an underwater natural history museum, while at the same time providing a cautionary tale of future loss. The villa’s beautiful and extensive garden is filled with works custom-made for the site and for this exhibition, which can be enjoyed in the day and also hosts special night tours when there is a full moon, accompanied only by the audio “white witch” guides, Patti Smith and Charlotte Gainsbourg. En route you can encounter works such as Ed Ruscha’s Sea of Desire, reproduced by the artist on a monumental scale, or Mathieu Mercier’s Diorama. Entering Mercier’s pavilion, the visitor encounters two real 'water monsters', axolotls, an endangered species from Mexico that has only survived by being transferred to a domestic or laboratory environment. Both works are equally thrilling in their different ways, though Mercier’s is movingly confronting.

Bianca Bondi, The Fall and Rise (2021) in the exhibition The Imaginary Sea at the Villa Carmignac © ADAGP, Paris, 2021. Fondation Carmignac. Photo: Marc Domage

Anne Racine, who rotates the presidency of the Plein Sud network, with Jean- Pierre Blanc, explains that the network exists to celebrate just such different creations and environments, and to showcase “the quality of life in the South: the land with its ways of life, sea, food, architecture and its manner of welcome is not separate from the experience of its art.” And, embracing this totality, a visit to each art venue will be accompanied by Plein Sud recommendations for the best local restaurants, hotels and beaches, using the contemporary art experience to revivify tourism of the area. At one of the best Porquerolles restaurant, one can sample a towering meringue and ice-cream confection, or alternatively a horizontal pairing of citron and basil sorbet, hiding under a flat layer of fennel leaves. Racine jokingly compares the one to a Gehry, the other to a Villa Carmignac. The network, she adds, makes no distinction between museums, art centres, sculpture parks, artist residencies, private or publicly owned art places: “We don’t care, as it’s not important from the visitor’s perspective. They just want to see nice places and great art.”

Villa Noailles in Hyeres