Hair dryers, televisions, type-writers and milk jugs are just some of the hundreds of plastic objects made in Communist East Germany between 1949 and 1990 that will be analysed in a research project involving the Getty Conservation Institute, the Wende Museum near Los Angeles and Die Neue Sammlung Design Museum in Munich.

The science of plastics conservation is a complex field that only began developing in the 1990s. Diverse plastics composed of varying materials and produced with different manufacturing processes age in dramatically different ways: while some plastics become brittle and crack, others begin to liquefy and ooze or bubble and warp. Many discolour.

Correspondingly, conservation requires a range of approaches, depending on the composition of plastics, says Odile Madden, a senior scientist at the Getty Conservation Institute. “A cellulose nitrate bowl will deteriorate differently from a cellulose acetate bowl, and therefore the care is likely to be different,” she says.

Watering cans for flowers and plants (1960) © Die Neue Sammlung—The Design Museum/A. Laurenzo; Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Trust

Information about conservation care remains inadequate, says Tim Bechthold, the head of conservation at Die Neue Sammlung, which has more than 1,000 East German objects made of plastic in its collection. “The goal is to put together a manual for museums and collectors to help them identify different materials and learn how they age, ideally with notes on how to treat them,” he says. The two-year project will result in an exhibition with the working title House of Plastics at the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich.

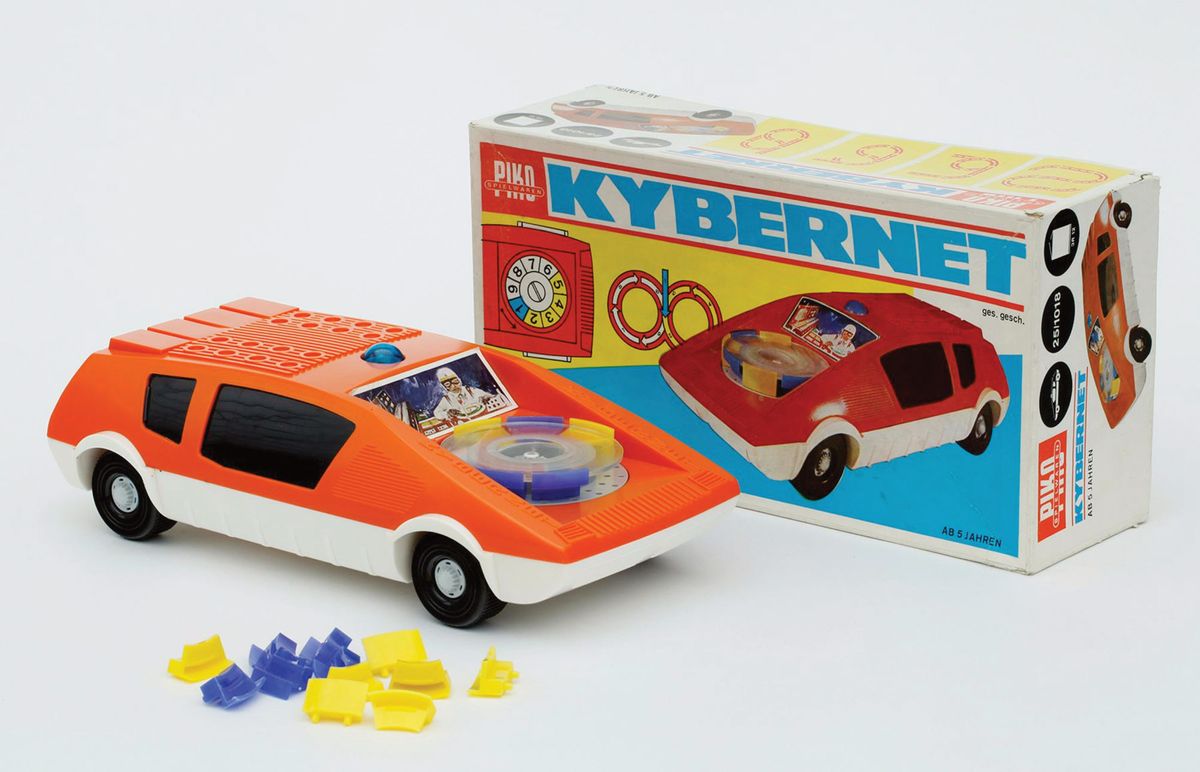

East Germany was a major manufacturer of plastics, exporting them widely across Eastern Europe and even to the West. Bechthold says that West German mail-order companies such as Quelle and Otto sold East German products such as cassette players under different labels to disguise their origins. Die Neue Sammlung’s collection even includes a Wartburg P70, one of the first cars to be made with a plastic body in the 1950s. The material used was Duroplast, a reinforced resin plastic.

The project will examine 600 items from East Germany in the collections of Die Neue Sammlung and the Wende Museum. The latter’s collection of Cold War artefacts was assembled by private collectors to preserve the legacy of the Soviet empire after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

Radio device SKR 730 (1990) © Die Neue Sammlung—The Design Museum/A. Laurenzo; Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Trust

Documents in the Wende Museum’s extensive archives may provide insights into the processes and substances used in East German plastics manufacturing, says Friederike Waentig, a professor of conservation at the Cologne Technical University’s Institute of Conservation Sciences and a member of the project team. While in the West, disposable plastic items such as razors and cutlery were in widespread use in the 1970s and 1980s, in East Germany “there was no throwaway mentality”, she says. “Products were made to last 30 or 40 years.”

The researchers’ first task will be to closely examine selected objects from the two collections to identify the components and processes used in the manufacturing, Madden says. This work requires scrutiny under microscopes and equipment such as infrared spectrometers and X-ray fluorescence spectrometers to analyse the materials used. Identifying the materials should allow the researchers to develop conservation methods accordingly, from preventive measures to optimise storage conditions such as protection from light or oxygen, to cleaning treatments for products that begin to liquefy, she said.

The different ways that plastic ages have one thing in common: they do not, in general, enhance the appearance of an object, Madden says. “The concepts of patina, or mellowing with time—like the romance of the ruined that we associate with metals and woods—do not apply to plastic,” she says. “Aside from the conservators and conservation scientists, no one is charmed.”