For Public Sculptures, a solo-exhibition of work by the New York-based artist Adam Milner, presented by the nomadic, non-profit museum Black Cube, 13 sculptures by the artist have been installed throughout New York City. But rather than presenting them in typical art spaces, the artist has tucked away these works in storefronts and other quiet, everyday locales.

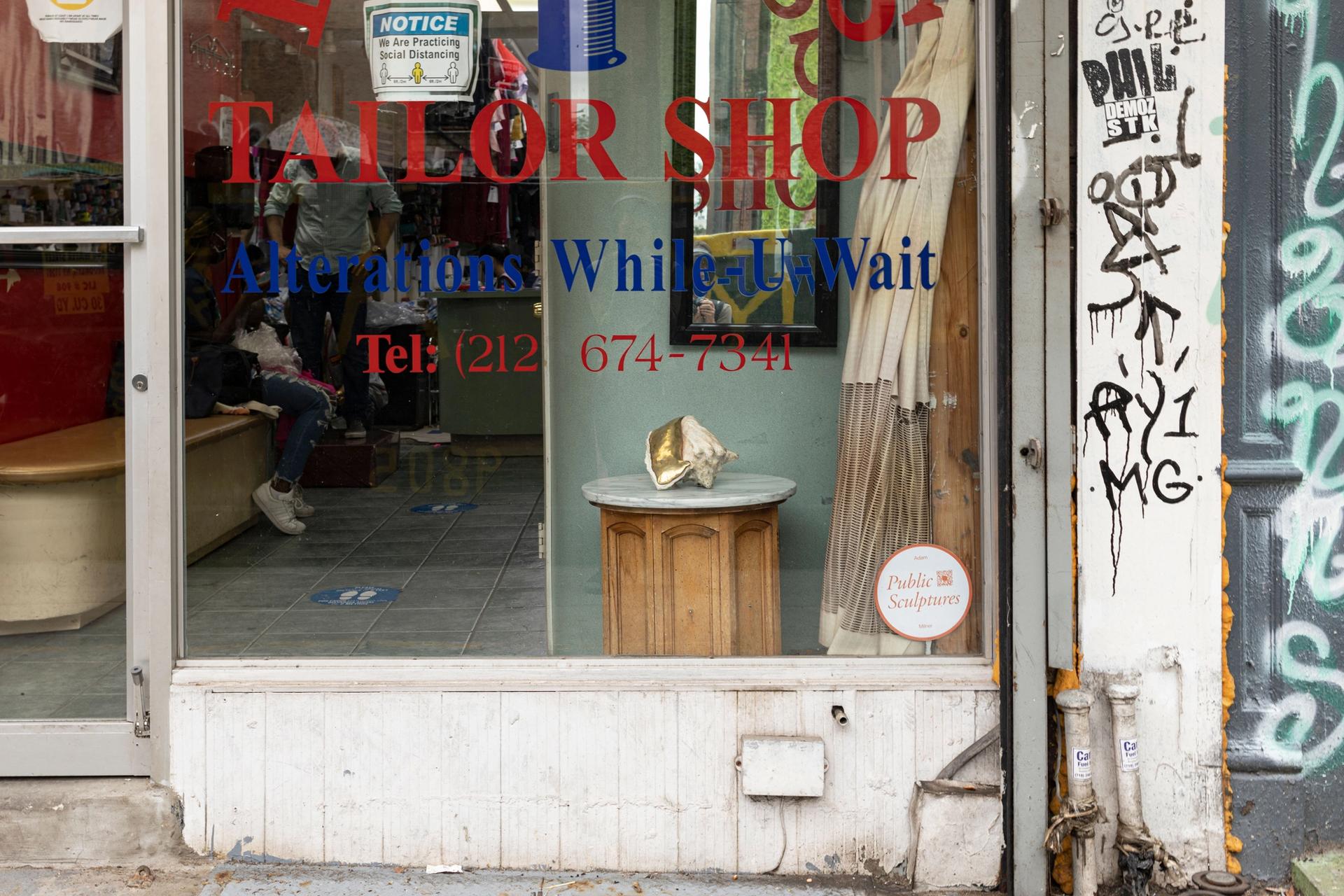

An untitled sculpture from 2019, made from cast bronze and a conch shell, is displayed in a tailor’s shop on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, while a 2021 mixed media work is presented in a bodega in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn. And while viewing these sculptures may entail some level of interaction with strangers, be it shopkeepers or patrons, others necessitate social communication more explicitly. Pink Cookie Museum Display (2021), for example, is displayed on a dog belonging to a friend of Milner’s, and you must text the owner to arrange a viewing time. Another work is displayed in a different friend’s car, which also requires a text exchange to set up a viewing. A map of all 13 works, along with viewing instructions, can be found on the project’s website.

“I knew I wanted these sites to be scattered enough across the city to intersect with different audiences,” Milner says. “On the other hand, they're all in places that I have some kind of connection with. That wasn't entirely intentional, it happened because those were the people who were excited about it or interested in it.”

Milner's Lime Green Apple Museum Display (2021), exhibited at Two Ways Supermarket in Brooklyn Image courtesy of the artist and Black Cube

Prior to finding homes for the works, Milner went through “several full days of walking door to door through New York City like a salesman,” seeking people and spaces willing to display the sculptures for the two-month duration of the show. “It was so vulnerable because, for the first two days, every single place I asked said no. I was just walking around talking to strangers, showing them my weird sculptures,” the artist says. “It made me realise how safe galleries and museums feel, and how they give art and artists a context that protects them a little bit. When I'm just out walking door to door, showing people my art, that feels way scarier than giving a lecture at a university or a museum.”

As can be consistently seen across the sculptures, Milner has always tended towards using life experience—such as relationships and personal totems—as source material for work that encourages dialogues about desire, intimacy, value, anxiety and other topics that undergird our daily lives but tend to remain infrequently discussed. Boyfriend’s Childhood Sword (2018), for example, is a glass replica of a mock weapon that the artist's ex-boyfriend trained with as a child; as a part of this exhibition, it can be found piercing a tree trunk in Greenwood Cemetery.

Public Sculptures (15 August) serves to facilitate these moments of interpersonal connections, which seem to ripple outwards from the objects themselves; there is the intimacy of Milner approaching individuals and entrusting them with an art object for two months, and there is the intimacy on the part of the viewer, who then engages with the store owners or reaches out to strangers in order to experience the work. “I do hope that my work can be a catalyst for some kind of exchange,” Milner says. “Sharing it often creates new experiences, connections, and opportunities for intimacy or awkwardness. This show is new, so I’m curious to see if it does that, or if the objects just kind of quietly sit there and eventually go away and maybe not change anybody’s life. If that happens, that’s okay too, but I do hope that maybe the tailor gets a new customer or someone buys flowers while looking at the sculpture, and then they have these flowers in their house and that connects them back to the work. In that way, they would have brought a little bit of it home with them.”

Adam Milner, Untitled (2019), cast and polished bronze, conch shell, is exhibited at New Express Tailor Shop in Manhattan Image courtesy of the artist and Black Cube

“Being an artist for me is about reimagining how to be in the world, and proposing new ways of being, thinking, and seeing,” the artist says, honouring the ways in which these sculptures may touch the lives of concentric audiences, whether it is those who house the works, those who encounter them unintentionally by frequenting a retail space or living in a certain neighbourhood, or the conventional art audience, who may seek them out as one would attend a gallery or museum.

That the works have this ability to expand into the quietude of our personal lives somewhat upends our modern notion of public sculpture, a phrase that more often connotes mammoth steel structures in plazas than it does the idea of texting a stranger and meeting their dog. “People often say my work has a form of institutional critique in it, and I think they're right, but I don't go into it with that mindset,” Milner says of this juxtaposition. “I'm just looking at the edges and the periphery and these quiet, weird little things in my life, and then that often ends up inherently critiquing dominant structures and status quo.”

Adam Milner, Bag in Bag (2019-2021), ceramic, screen-print on thrifted cellophane, ribbon, exhibited at SSS DVD Video Corp in Queens Image courtesy of the artist and Black Cube