Originally scheduled for April 2020, the pandemic pulled the plug on Glasgow International (GI), Scotland's largest visual arts festival, at the eleventh hour. Now, along with the Uefa European Football championship, the rebooted GI has been one of the first major events to kick off after the city’s protracted lockdown lifted earlier this month. The resurrection of the festival's ninth edition has been an especially remarkable feat, involving over 100 artists both local and international in more than 30 spaces throughout the city, which encompasses both familiar city landmarks as well as new, evocative venues not usually associated with contemporary art.

Alberta Whittle’s new film business as usual:hostile environment (2021) explores the colonial history of the Forth and Clyde Canal and how waterways shape race, class and migration. It is all the more powerful for being screened on a truck-mounted screen set against a panoramic view of Glasgow. While Nep Sidhu’s procession of vast tapestries and accompanying film Black (W)hole (2021) deals with Sikh history, ritual and traditions and also plays with and off the bombastic Victorian pomp of the main central space of Glasgow’s Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA).

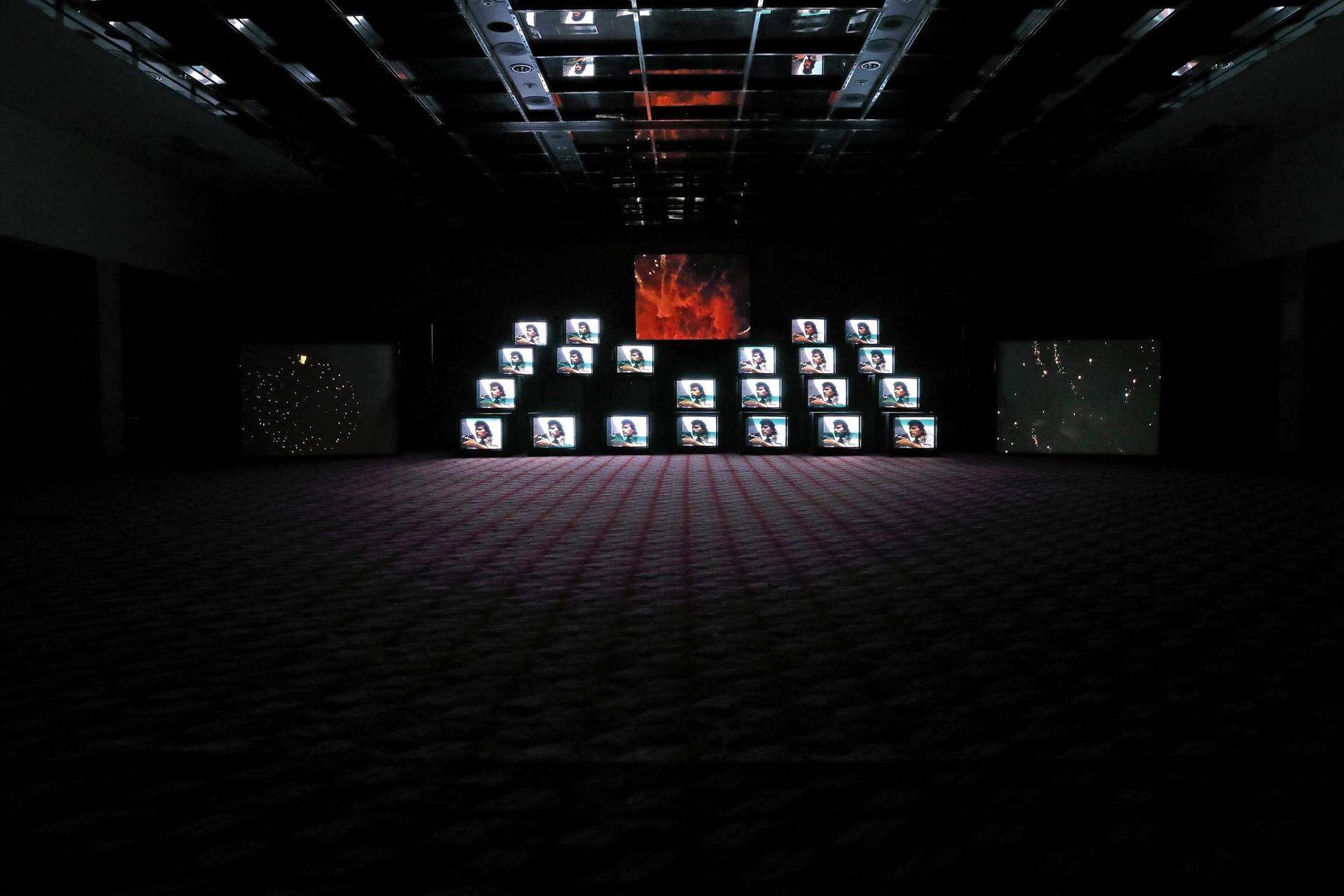

Gretchen Bender, Total Recall (1987) at Royal Concert Hall Photo: Matthew Arthur Williams

The rich history of the Barrowland Ballroom, home to innumerable historic gigs, gives additional context to Duncan Campbell’s 2006 installation work Oh Joan, No...,which suspends a giant screen in the pitch black vast empty space. Occasionally the encompassing darkness is animated by random flurries of sound—a laugh, a moan, a sigh—and momentary flares of light from a streetlamp, a theatrical spotlight or a lit cigarette. Anticipation builds for a main event that never happens in a Beckettian tribute to the power of insignificant detail. More histories are interrogated at Glasgow Woman’s Library where Ingrid Pollard has responded to the library’s rich archive of lesbian material by bringing it out from the vaults. Filling the building with vivid displays of strikingly designed visual material, Pollard has also unearthed personal audio accounts of individual experiences that now emanate from between the volumes on the shelves. No Cover Up (2021) celebrates the many strands and movements within LGBTQ+ history and culture, as well as the enduring importance of great design and visual flair in getting a message across.

The overarching theme of GI is Attention. Although decided upon pre-Covid, the idea has accrued new emphasis and wider meanings given the radical changes in what we now have been forced to pay attention to, globally, nationally and personally. As GI director Richard Parry says, “everything has changed around us in the past year, the way we pay attention has changed as well”. This notion of attention held, redirected and distracted reverberates in myriad ways throughout the works on show. The shattering of our attention is directly addressed in Gretchen Bender’s Total Recall (1987), a monumental multichannel video installation involving 24 stacked TV monitors and three projection screens installed in Glasgow’s Royal Concert Hall. This pioneering and prescient work was made over three decades ago but predicted our current digital attention-deficit age by presenting a fast-paced, retina-searing bombardment of images, graphics and collaged fragments, sourced from TV commercials, films and advertisements.

Georgina Starr’s Quarantaine (2020) Photo: Matthew Barnes

Overall there is a predominance of film and video work at this GI, presented in myriad formats. At Tramway arts centre, Georgina Starr’s Quarantaine (2020) offers a lengthy narrative extravaganza of girl power, body parts and an Occultish cult on a conventional single screen. And there are more elaborate fantasies in Jenkin van Zyl’s grotesque but also oddly tender libidinous horror movie, Machines of Love (2020-1). Playing in an immersive setting of airplane seats and fuselage it also features the heads of its six ghoulish protagonists displayed in refrigeration units. At Tramway 2, Martine Syms has built a giant scaffold-like sculptural structure to house She Mad S1: E4 (2015-2021), four coruscating films shown in rotation that use a wide range of historical and contemporary footage to trace American TV and media representations of Black experience.

But having been forced to view so much art on screens over the past few months, there is a very particular pleasure to be found in a direct encounter with the physical stuff of analogue art, whether in the very different but also oddly complementary paintings of Carol Rhodes and France-Lise McGurn in the Kelvingrove Museum or the abundance of surprising textures and materials to be found in the show of new sculpture by Eva Rothschild at the Modern Institute.

Not part of the official programme but well worth seeking out for its meaningful marks is an excellent show in the elegant Georgian interior of 42 Carlton Place which pairs the pioneering abstract investigations of the 1930s painter and textile designer Paule Vézelay with the complementary paintings and prints of contemporary Glasgow-based Louise Hopkins.

Jimmy Robert, Untitled (belladonna) (2007/2015) Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Leighton Gallery

But the ultimate tainted and complicated multi-sensory experience can be found at the Hunterian Art Gallery. Here the Guadeloupe-born, Berlin-based Jimmy Robert has drawn on the museum’s historical collections to explore Scotland’s links to the Caribbean via wide ranging references to the tobacco trade incorporating elements of both art history and his personal life. These range from Rennie Mackintosh tobacco flower textile designs and an etching plate by James McNeill Whistler of his Parisian Creole mistress to a film of Robert’s formidable mother smoking a Davidoff cigar on her Guadeloupe veranda. Echoing through the stairwell we hear the sound of this formidable matriarch drumming and reciting a poem celebrating female strength. Less obtrusive but arguably more pervasive is a stretcher mounted sample of so-called Jamaica Tartan which makes its olfactory, as well as its visual, presence known by being impregnated with Tom Ford’s Tobacco Vanille eau de parfum. This wafts through the space, marrying the luxurious, complicated stench of capitalism and colonialism, lest we forget.

Five key projects

Installation view of Martine Syms's S1: E4 (2021) at Tramway Photo: Matthew Barnes

Martine Syms: SHE MAD S1:E4, Tramway

An extensive scaffold structure zig-zags across this cavernous former tram shed, creating multiple vantage points through which to watch Syms’ four-part film work which addresses the way representations of Black identity and gender have been shaped throughout the history of the moving image. These complex works keep viewers moving through the space by being shown in rotation. There is a filmed lecture on race in American sitcoms too, as well as fragments of footage from internet, social media, phone and surveillance footage and even a specially created avatar as Syms keeps us physically and intellectually on the move in this powerful and painful gesamtkunstwerk.

Installation view of Nep Sidhu's An Immeasurable Melody (Medicine for a Nightmare) at GOMA Photo: Matthew Arthur Williams

Nirbhai (Nep) Singh Sidhu: An Immeasurable Melody (Medicine for a Nightmare) and Black (W)hole, GOMA

For his first solo exhibition in Europe, Nep Sidhu has created vast tapestry and multimedia works as well as a monumental marble and metal sculpture and a stunningly-shot meditative film. All of this is steeped in Sikh metaphysics, symbolism and ritual as well as Sikhism’s often bloody history of persecution. There’s a particular focus on the role of sound and rhythm, and while much of the content and meaning may be lost on the non-Sikh viewer, the sheer visual impact of this work and its abundance of vivid, if enigmatic, detail offers a glimpse into the infinitely rich culture of the world’s fifth largest organised religion.

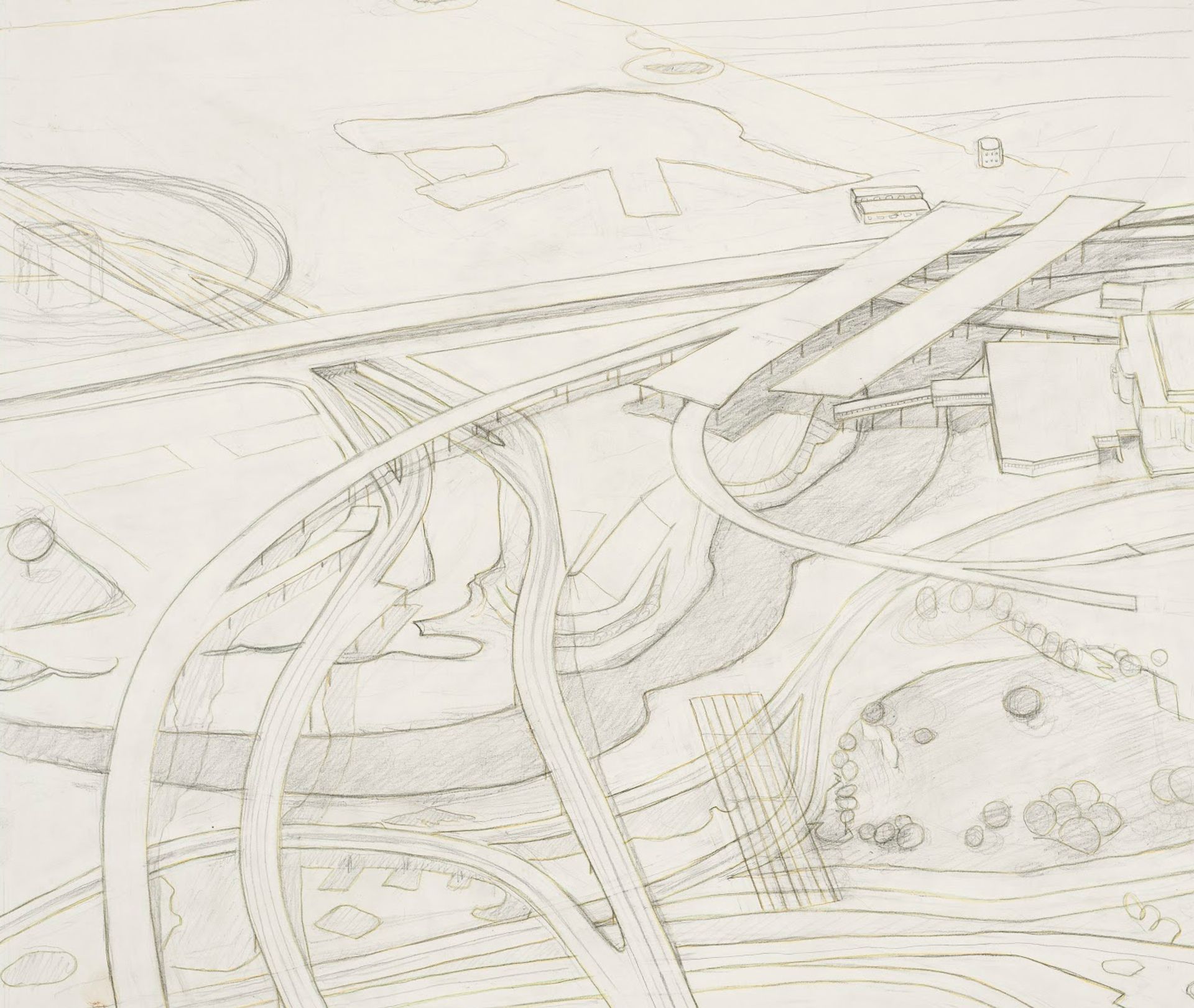

Carol Rhodes's River, Roads (2013) Courtesy of the estate of Carol Rhodes

Carol Rhodes: See the World; France-Lise McGurn: Aloud, Kelvingrove

McGurn’s exuberant, fluidly executed overlapping figures pay homage to Albert Moore’s Victorian painting of lounging Neoclassical women in the museum’s collection, loved by the artist since her childhood. But here these languorous ladies are given a new lease of vivid contemporary life, painted across a processional frieze of giant glass panels, wood framed like a museum cabinet, and saucily topped off with a neon originally shown in a nearby nightclub. Downstairs a show of the late Carol Rhodes’s strange, sober paintings and drawings of depopulated but human-made landscapes—airports, quarries, carparks and solitary caravans—are more slow burning but become increasingly odd, bodily and complicated the more time you spend with them.

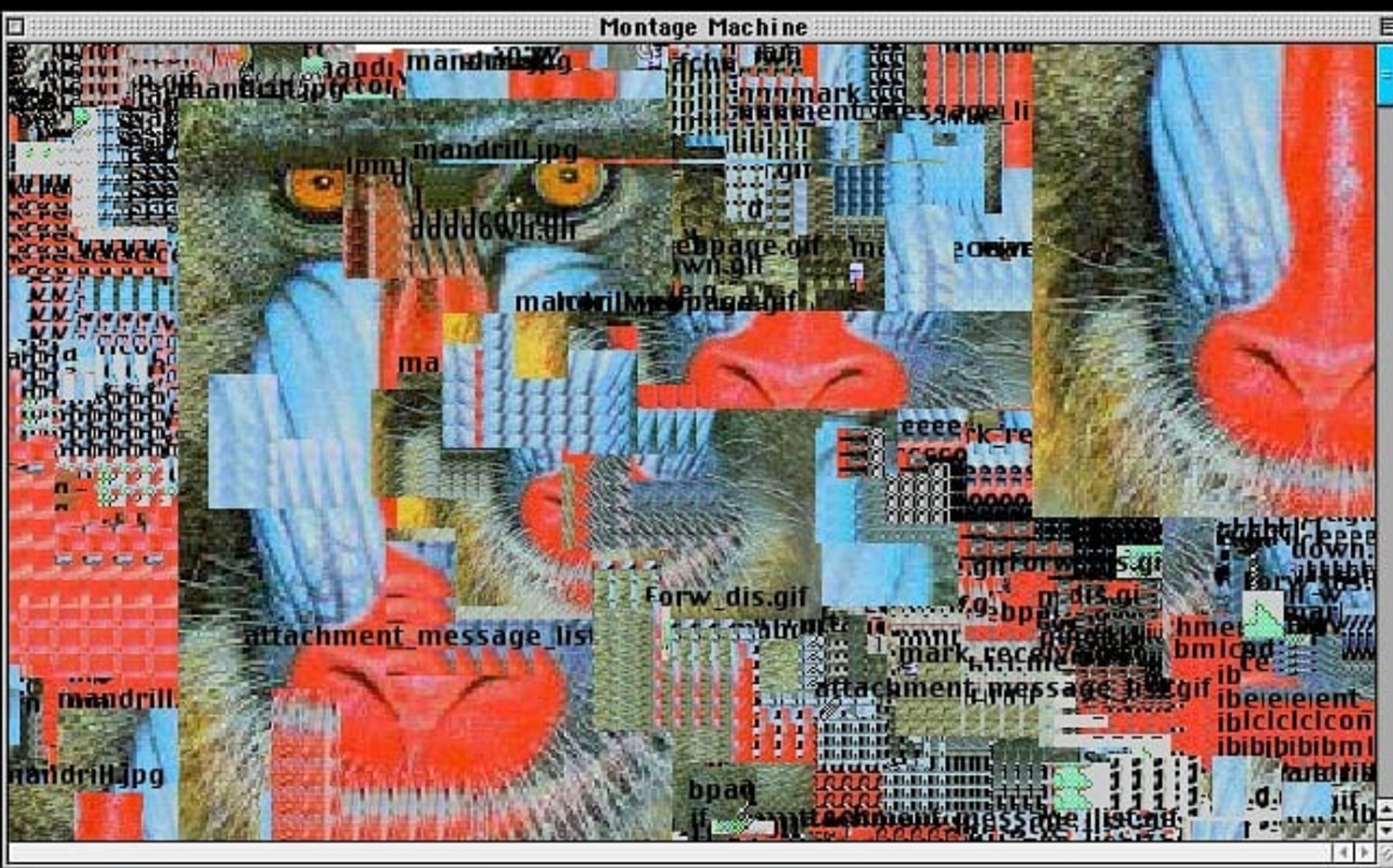

Screenshot of the Montage Machine from the work donald.rodney:Autoicon v1.0 Courtesy of Gallery Celine, Glasgow

Donald Rodney, Gallery Celine

This artist-run space housed in the faded grandeur of a Georgian apartment opposite Queens Park railway station is playing host to the first presentation in Scotland of the late Donald Rodney, a leading and inspirational member of the BLK Art Group of artists in the 1980s. An interactive computer generated work, AUTOICON, draws on Rodney’s archive and writings to answer inputted questions from visitors about the artist and his work while the 1995 film 3 Songs Pain Light and Time made by Edward George and Trevor Mathison pays an intensely moving tribute to this hugely important artist and his work.

Installation shot of Eva Rothschild at the Modern Institute Courtesy of The Modern Institute

Eva Rothschild: Peak Times; Luke Fowler: Index Cards and Letters, The Modern Institute

Rothschild’s new work uses a multitude of materials and textures to push the possibilities and conventions of sculpture. These range from a Brancusi-like column of multicoloured rolls of gaffer tape cast in jesmonite, sittable-on sculptural couches upholstered in elaborately dyed fabric, batik wall pieces and a sculpture that seems to be melting into a dribbling sheet of liquid plastic. In the gallery’s other space, two 16mm films by Luke Fowler portray his parents via the written word: we discover his sociologist professor mother through her meticulous index card records of the books she has read and get to know his late political philosopher father through his correspondence with his oldest friend Dan O’Neil, a Marxist academic living in Australia.

• Glasgow International 2021, various sites, until 27 June