On 14 May, the Whitney Museum of American Art launched the first episode of Artists Among Us, a five-part podcast series exploring David Hammons’s Whitney-commissioned public sculpture, Day’s End. The podcast’s host is the artist Carrie Mae Weems. As Weems tells us in the first episode, the podcast is about far more than Hammons’s work, exploring the history of New York’s Meatpacking District, the famous piers on the Hudson River, and the short-lived Gordon Matta-Clark work Day’s End, cut into Pier 52, to which Hammons’s project is a ghostly memorial. It explores, Weems says, “the fascinating ways that his sculpture invites us to reflect on the past of this site—who lived there, who worked there, and then, how it all changed”.

Artists Among Us is the latest podcast in which artists speak directly to us through the medium. And just as notable as big documentary productions like the Whitney’s are more informal, but no less profound shows like the painter Emma Cousin’s Chats with Artists in Lockdown, launched as the pandemic began. It is now an oral history of artists’ experiences during the serenity or anxiety of lockdown and its aftermath, amid the postponed shows, the childcare crises.

Artists’ podcasts are not a new phenomenon: Bad at Sports was founded by three Chicago artists in 2005 and is still going strong. But there is an increasingly broad range of productions with artists at the helm. They offer, in different ways, access to the unique communion between fellow makers, capturing the often unexpected ways artists think about creative acts and the works that emerge from them.

The artist Carrie Mae Weems Photo: Audoin Desforges

David Hammons himself rarely gives interviews and does not feature in person in Artists Among Us. “Though his voice is not heard in the podcast,” says Anne Byrd, the Whitney’s director of Interpretation and Research, who led the development of the podcast, “we feel that his work has created a space for the many absences and invisible histories of the site to speak.” Also, Hammons “is not only influential, he also inspires a lot of passion”, Byrd says. “We were fortunate to be able to talk to many great artists, writers and thinkers for the podcast because all were excited to speak about his work.”

Though not an exact contemporary, Weems gains a similar respect from fellow artists, so her role in knitting together these interviews, more than 30 in total, is key. The podcast needed the voice of a major artist to achieve the necessary gravitas. As Byrd says: “Weems proved to be the perfect host for the podcast because she was able to frame the dialogue between the work of art and the site’s history in ways that were both engaging and informative.”

In Artists Among Us’s first episode, Weems gets to the heart of Hammons’s particular brilliance. “One of the beautiful things about David is that he offers the audience the richness of an art experience, whether they know they’re looking at art or not,” she says. “I think he’s a master.”

Emma Cousin’s podcast started partly out of feeling “quite desperate”, a sense of helplessness as the UK was gripped by Covid-19: “What can we do? How could we help at this time, given we’re not nurses?” She had some unrecorded conversations early in lockdown “and it felt like the things we were talking about were more than just the fact that our shows were cancelled. It was like the state of the arts in today’s society”. She had the conviction that, if she recorded the conversations, “other artists might start to get in touch, or get in touch with each other”, she says. “And that’s happened, definitely, through the podcast.”

The emphasis is on “chats” rather than interviews. Cousin does rigorous research and has questions common to each episode—“How are you feeling?” at the start, and then, at the end, questions about what has been helpful for the artists during this period and what they have learned about themselves. But the podcast’s charm is precisely that, as the artists discuss the personal effects of the pandemic and wider events in their lives, we hear the kind of intimate, unguarded conversation that might ordinarily happen in the studio at the end of the day or in the pub after an opening—circumstances often denied to artists amid coronavirus restrictions. “Were we feeling ecstatic to have this almost self-imposed residency, or were we feeling like our career was being put on hold?” Cousin says. “And a strange tension, actually, between the pressure to continue to make work or the possibility of just being at a different pace and trying to embrace that and not feel too stressed about it.”

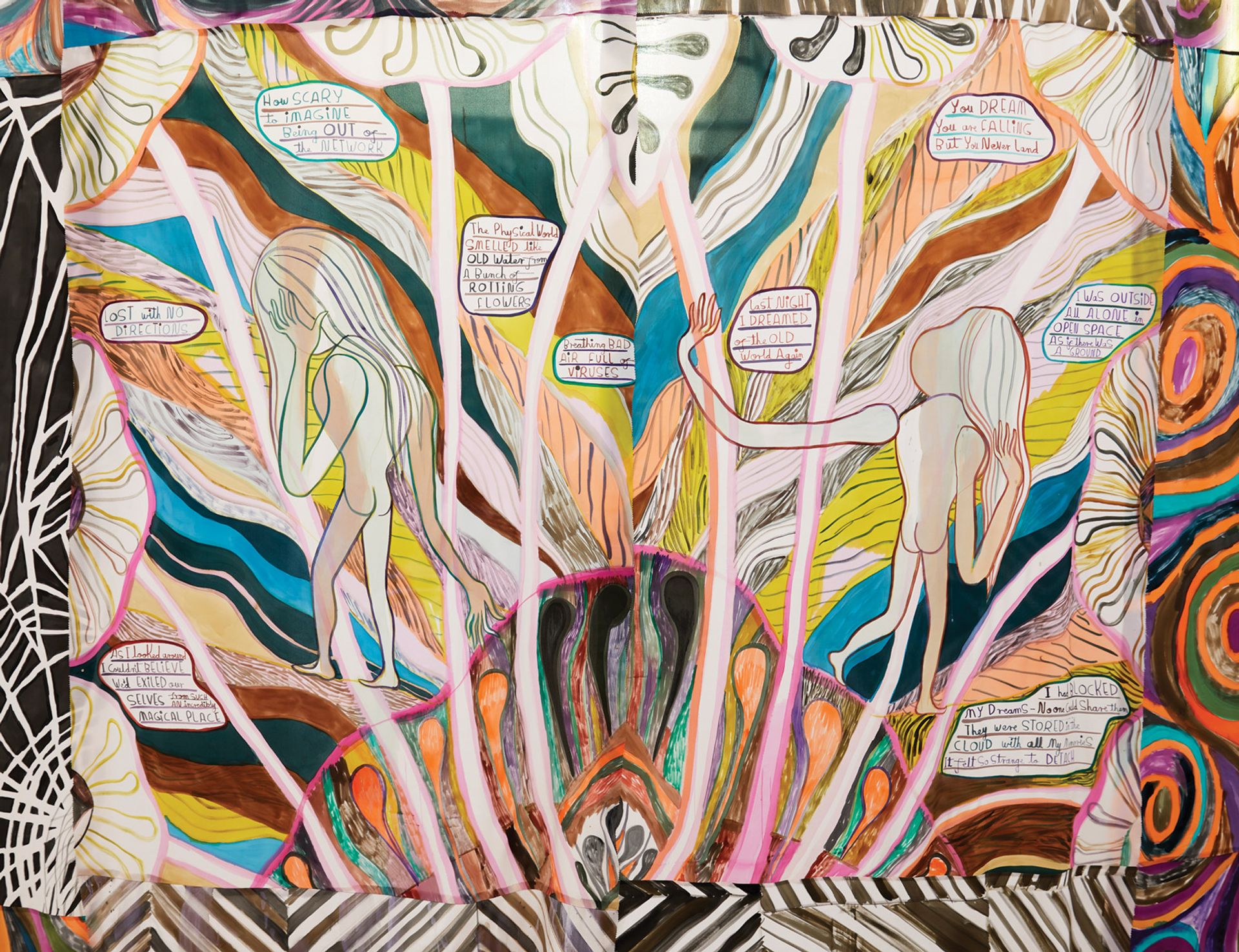

Emma Talbot, When Screens Break' (detail) (2020) © Stuart Whipps

At times, this leads to moving sequences, as artists reflect on personal loss and suffering. Emma Talbot speaks of the early death of her husband and its effect on her ability to make work, of the pandemic hitting a moment when numerous big shows were about to open and developing a new body of animated work. Lana Locke reflects on Grenfell Tower, where she had once lived, and how, on its third anniversary, the disaster had been somewhat forgotten amid the Covid crisis. “It felt like that was an opportunity for her to speak about that trauma, and that struggle, which is ongoing, and that she’d made work about,” Cousin says.

Cousin admits to starting to make the podcast as “a complete novice who knows nothing about editing or software or recording or anything to do a podcast”. But, she says: “The great thing about being a novice is that it’s okay to be learning forever… That kind of curiosity and fascination—like wonderment—is, I would say, a fundamental part of artists.” And while she is conscious of the documentary importance of the interviews and of the increasing professionalisation in her podcasting, she says, “You don’t want to be too reverent. You want to be in it and buzzing with it.”

• Artists Among Us and Chats with Artists in Lockdown are on the usual podcast platforms