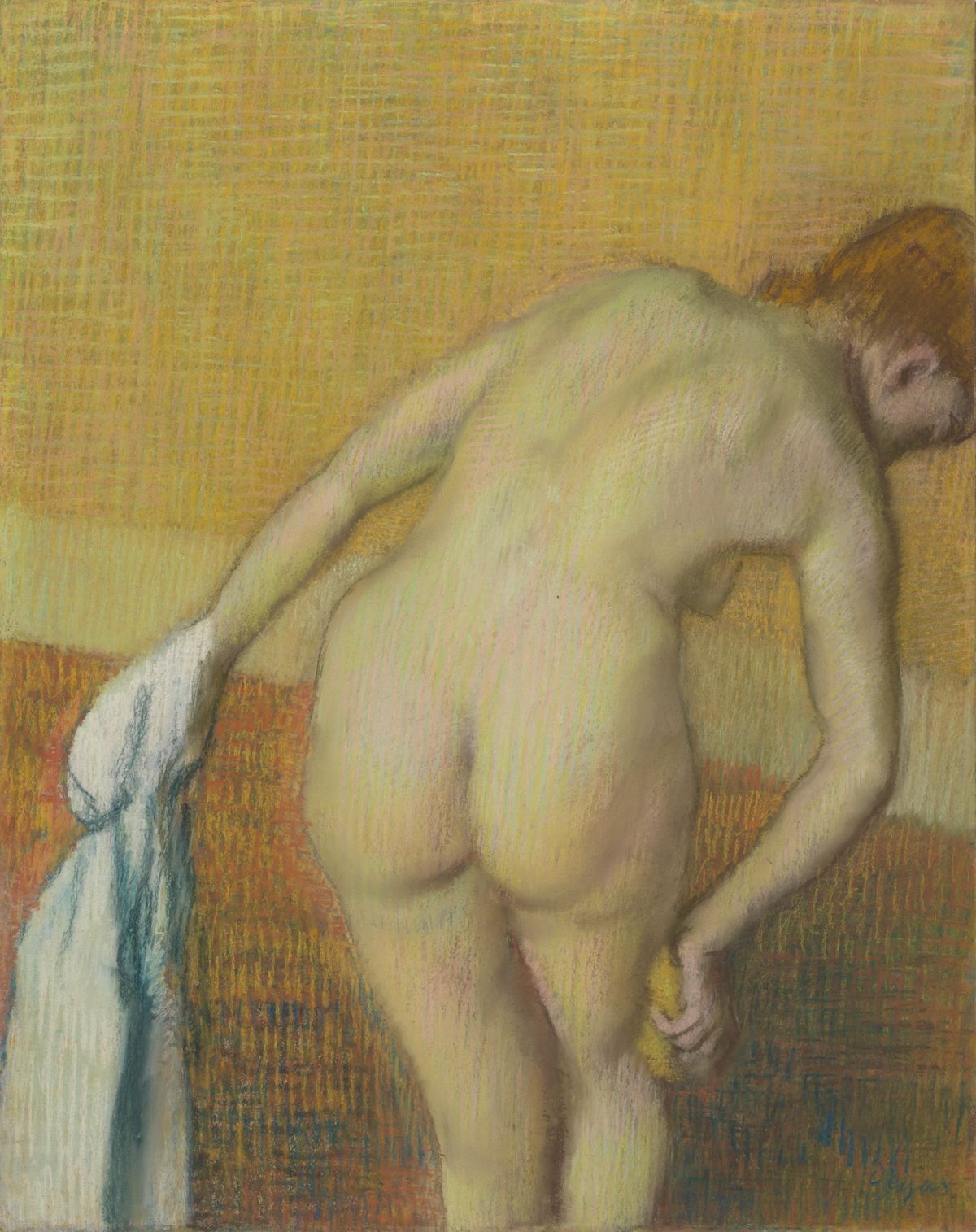

The Van Gogh Museum reopened after a six-month lockdown this week, inaugurating an exhibition on acquisitions of the past ten years. Most spectacular is a Degas pastel, Woman Bathing (around 1886). The subject matter—a nude woman seen from behind—has stirred up a controversy.

Bought at Sotheby’s in November 2019, for $6.6m, the Degas was certainly an ambitious purchase for a museum. Late in the evening of the New York sale, the Van Gogh Museum’s curatorial staff gathered in an Amsterdam hotel bar to hear whether their bid would be successful. The curator Fleur Roos Rosa de Carvalho recalls: “We cheered so loudly that we were politely, yet firmly, ejected from the posh lobby”.

Curator Fleur Roos Rosa de Carvalho (on the right) hanging Degas’s Woman Bathing Courtesy of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam; photo: Jan-Kees Steenman

The Degas is now on display in Here to Stay: a Decade of Remarkable Acquisitions and Their Stories (until 12 September). Acquisition exhibitions are, by their nature, a mixed bag of artworks and can be dull. But this show springs to life, thanks to the stories that are told about the objects. One of the delightful characteristics of the Dutch is their frankness, and this comes through in the tales—which are far from bland.

As the exhibition texts explain, “the debate about the bare bottom in this Degas pastel dominated the art pages of the [Dutch] newspapers for weeks”. The question being asked was “whether in this day and age it is still possible to acquire and exhibit a female nude drawn by a man”.

Roos Rosa de Carvalho recalls that she received a letter from a painters’ model describing how posing nude is her profession, in which she takes pride. This made the museum curator think about Degas, concluding that “if we assume without question that she [Degas’s model] was the unwilling victim of a sex-obsessed artist, then perhaps we are not only failing Degas but her as well”.

Emilie Gordenker, the director of the Van Gogh Museum, was inevitably drawn into the controversy. She admits that “we had an internal discussion about the fact that some visitors might be offended by seeing a female nude”.

Following news of the acquisition and the subsequent debate, Gordenker found that people had got the impression "that we considered removing the work from display”. She indignantly rejects this suggestion: “Nothing could be further from the truth—we welcome the discussion, which is as old as the hills, and the Degas has been on show since its acquisition.”

Vincent may never have seen Woman Bathing, but he and his brother Theo saw similar works and were great admirers of Degas’s nudes. In 1886, after his arrival in Paris, Vincent had written that “though not being one of the club, yet I have much admired certain Impressionist pictures—Degas, nude figure—Claude Monet, landscape”. Theo, an art dealer at the Boussod & Valadon gallery, bought Degas’s works and held an exhibition of his pastel nudes in 1887.

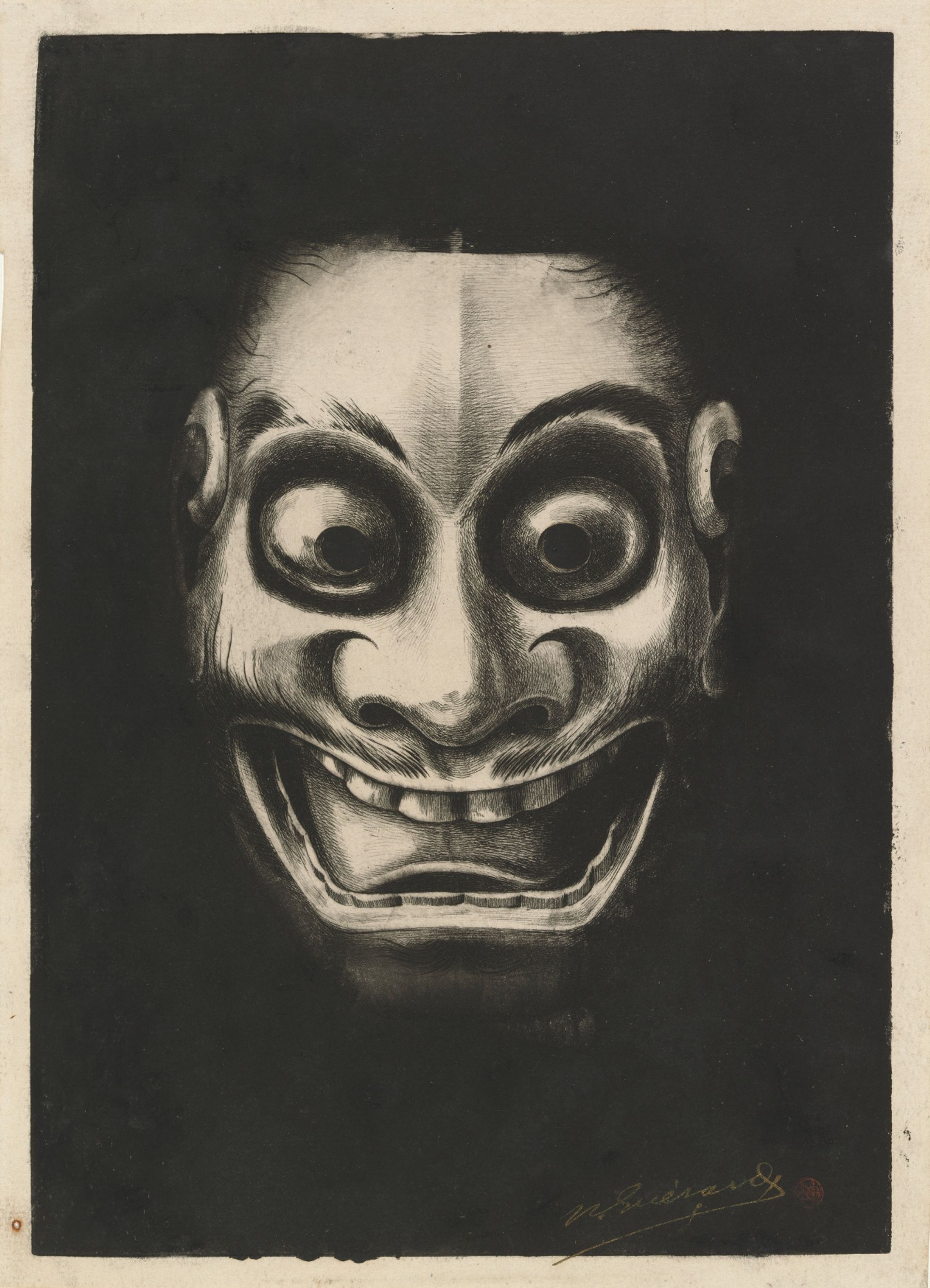

Henri Guérard’s Antique Theatre Mask from Lacquered Wood (1882) Courtesy of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Other works in the Here to Stay exhibition include a dramatic print by Henri Guérard of a Japanese mask and Gauguin’s Nave Nave Fenua (Delightful Land) from his Noa Noa series (1894). What makes the Gauguin print particularly interesting is its minor damage: small holes and the imprint of rusty drawing pins in the corners. These marks suggest that Gauguin tacked it to his wall, since a later collector would have been unlikely to have treated a print so casually. Other works in the museum’s acquisitions show include pieces by Van Gogh’s contemporaries: Monet, Caillebotte, Morisot, Pissarro, Signac, Toulouse-Lautrec and Munch.

What may come as a surprise is that the one artist the Van Gogh Museum rarely buys is Van Gogh. This is partly because of the sheer size of its founding collection, but mainly because of the prices now fetched for his works.

Vincent van Gogh’s watercolour Pollard Willow (July 1882) Courtesy of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (purchased with support from BankGiro Loterij, Vincent van Gogh Foundation, Rembrandt Association and her Prints and Drawings Fund, Mondriaan Fund and VSB Foundation)

Included in Here to Stay are the two paintings bought in the past decade. The watercolour Pollard Willow dates from 1882, when the artist was working in The Hague, and it was purchased in 2012 for £1.3m. Two years ago the Van Gogh Museum museum joined with the Drents Museum in Assen to buy Peasant Burning Weeds (1883) for $3.1m. This was the first Van Gogh oil painting to be acquired by the museum since 1977.

However, both pictures date from Van Gogh’s early Dutch period, for which prices are lower. It would now be very difficult for the museum to buy works from his later French years, which are much more expensive. Instead the museum concentrates on building up its collection of works by Vincent’s contemporaries, usually artists he admired.

And for those unable to see Here to Stay, because of Covid travel restrictions, there is a brief online guide to the show with installation photographs.