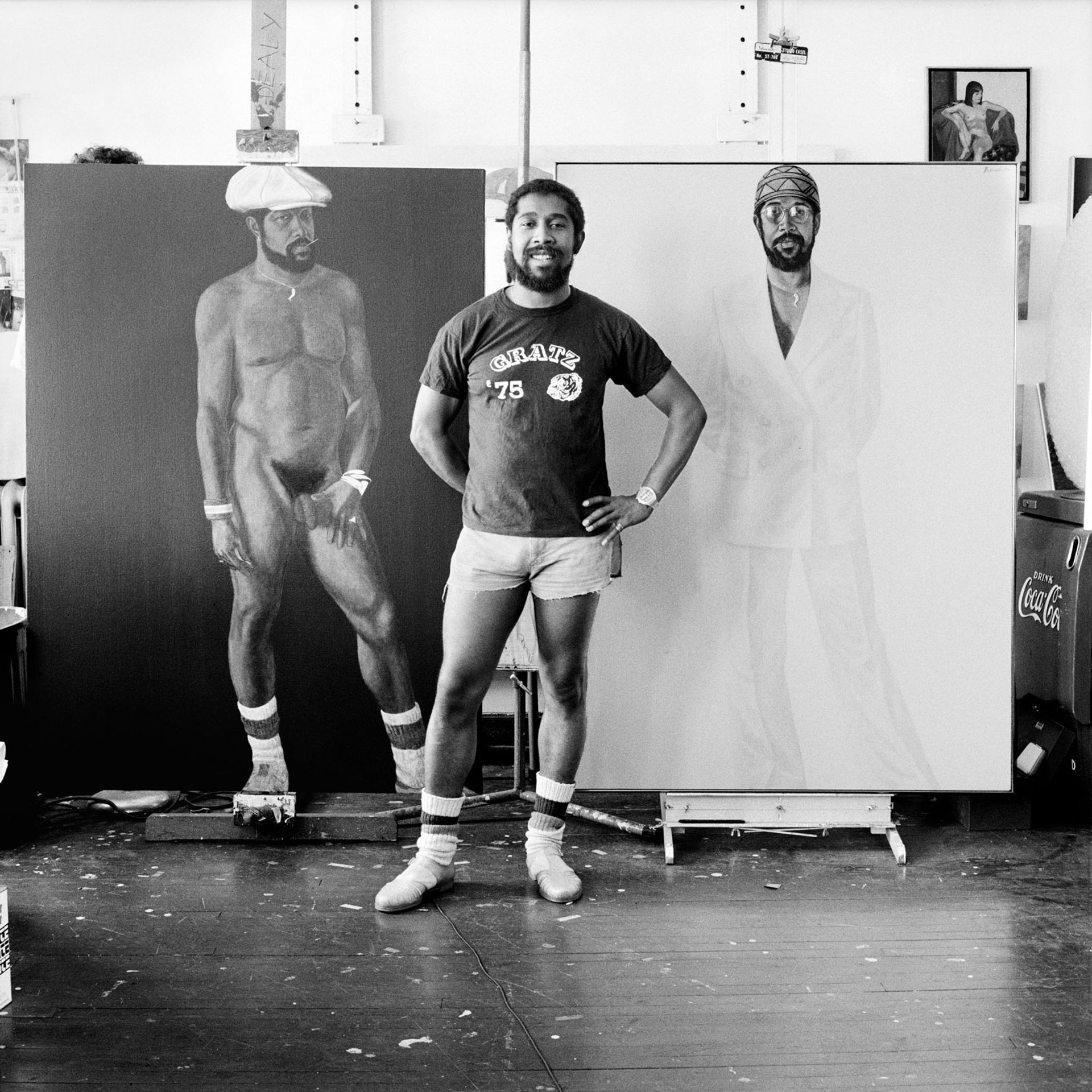

The US artist Barkley L. Hendricks (1945-2017) was considered primarily a painter, known for his depictions of cool swaggering figures in full length portraits. But photography also formed part of his practice, remaining an “underdiscussed dimension of his art” according to the sleeve notes for a new publication, Barkley L. Hendricks: Photography, which includes more than 60 photographs taken between 1965 and 2004. Hendricks initially specialised in photography; at Yale University, where Hendricks did his master’s in fine art, he was tutored by the renowned photographer Walker Evans.

Some of Hendricks photographs mirror his full-length paintings of friends and colleagues; other images capture casual domestic scenes, American landscapes, and city scenes, sometimes with an element of quiet humour such as Sit, Stay (1978/2013). After the artist’s death in 2017, Hendricks’ widow Susan and the New York dealer Jack Shainman catalogued his trove of photographs (this volume is the fourth in a five-part series dedicated to Hendricks’ life and work).

The assistant professor of African American and Black diasporic art at Princeton University, Anna Arabindan-Kesson, writes in the foreword about being photographed by Hendricks, and how aspects of his painting and photography overlapped.

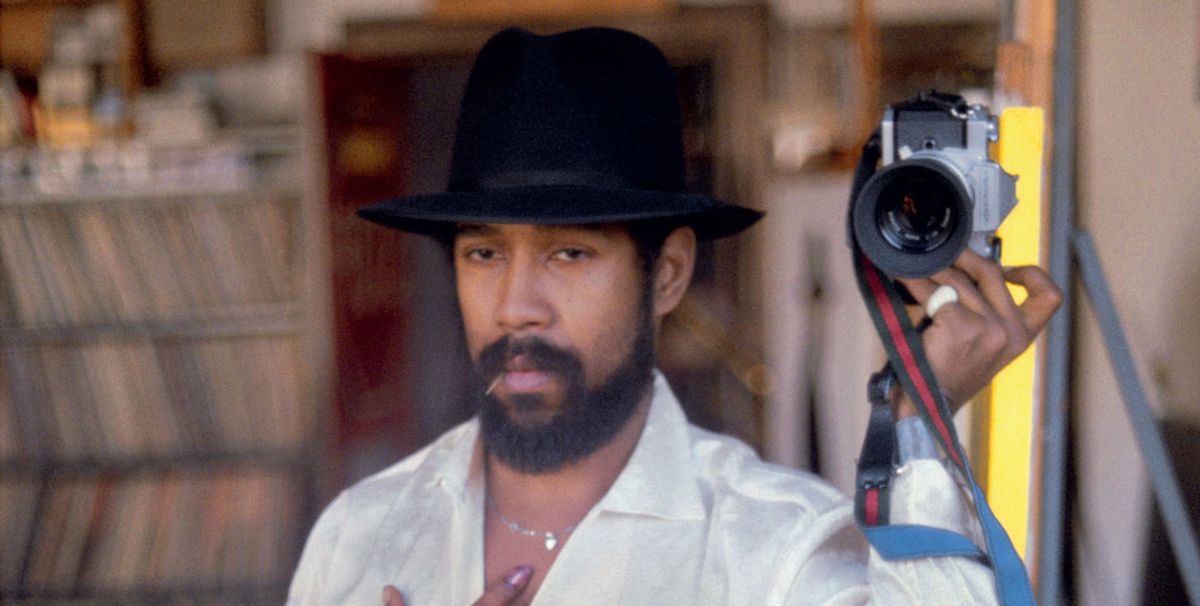

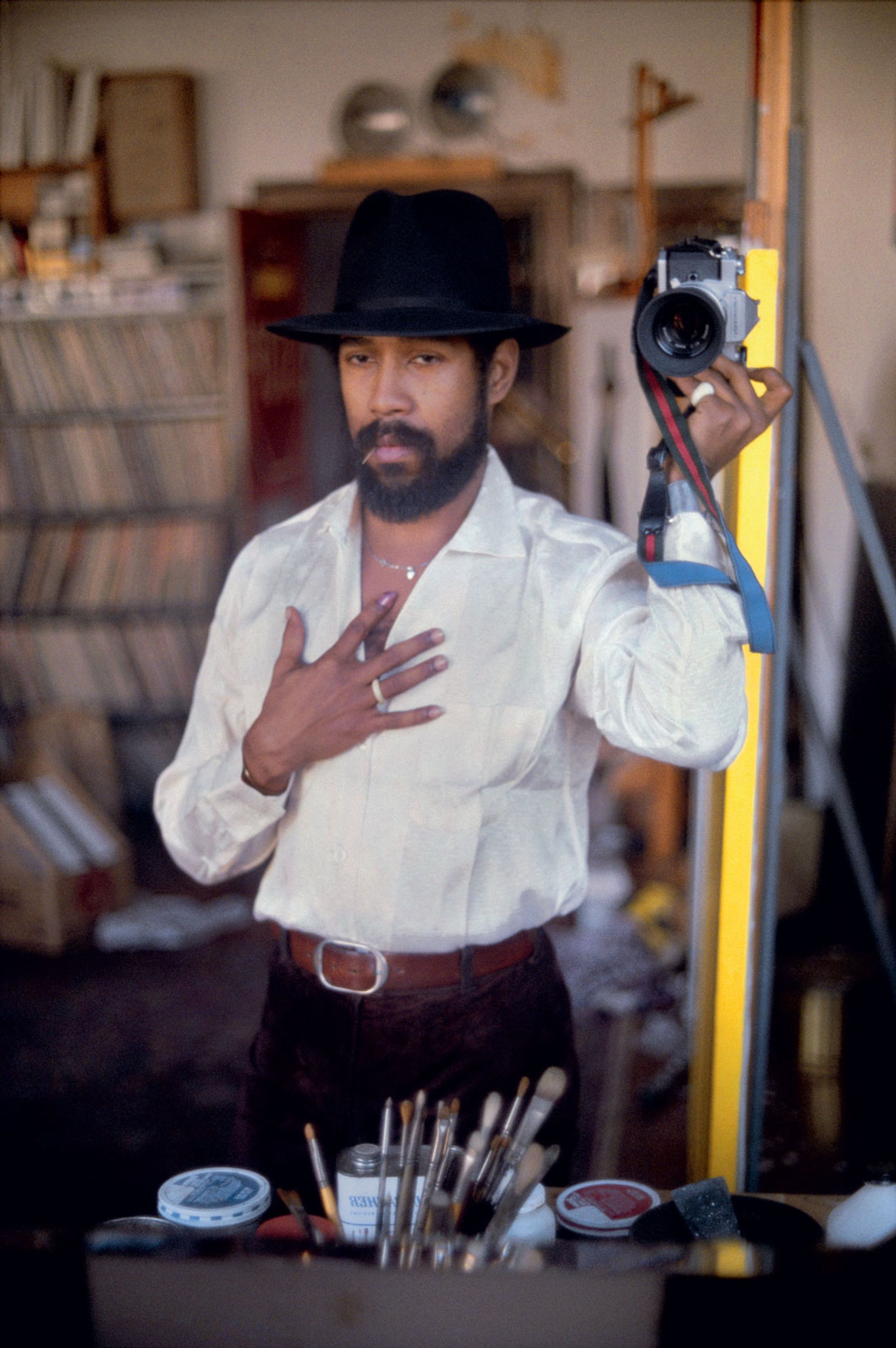

Barkley L. Hendricks, Self-Portrait with Black Hat (1980/2013) © Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Jack Shainman Gallery

Anna Arabindan-Kesson on Barkley L. Hendricks:

It was through photography that Barkley L. Hendricks got out into the world. He was an observer of people, places, scenes, and also, as he ex-pressed to me, an observer of the medium. In learning the zone system he learned to better visualise and modulate the tonal ranges (of black, grey, and white) in a scene. This seems to have sharpened the clarity and precision of his gaze. Photography enhanced his “eye,” it helped him better understand how to look: as in looking at a scene to understand how it came together, and learning to understand how a scene, a way of looking, could be arranged.

From its early beginnings, the photograph promised a new form of recording that could keep pace with modernity: it lit up what was dark and hidden, it found the fleeting and momentary and it had the capacity to intervene in time by capturing a disappearing past. Working back from, and around, his education with Walker Evans, we might then situate Barkley’s urban exploration, his detailed arrangements and his attention to the photograph as document, in conversation with the street photography of Robert Frank, the narrative eye of Gordon Parks, the visual dynamism of James Barnor, the monumentalising quietness of Berenice Abbott, or the textured sophistication of Eugène Atget, who also understood the ways photographs could be source material, documents for artists.

But, as it was for Atget, so too for Barkley the photograph was also more than what it showed, more than a document that retained, or remained after the fact. Barkley’s photography is relational. In many ways it was a performance, that “follow[ed] the event, not knowing the conclusion in advance,” [said Margaret Iversen].

This is not a reference to the ways his photographs were sometimes translated into paint, but a way to understand his photographic process and describe how his photographs disclose themselves to viewers. Rather than merely a tool for recording events, the camera is a mode of discovery, the photographic act always attentive to, and curious about, the world outside.

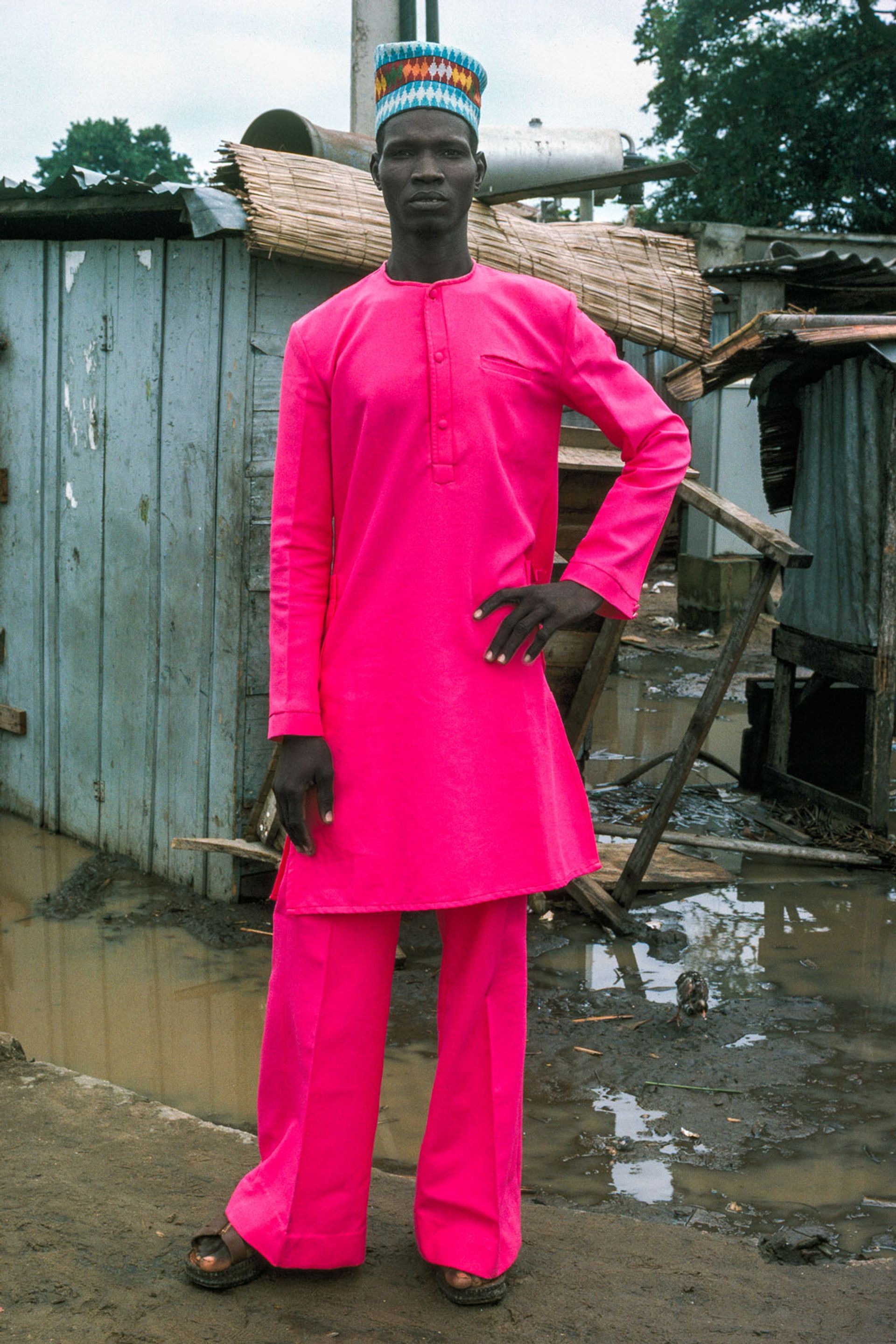

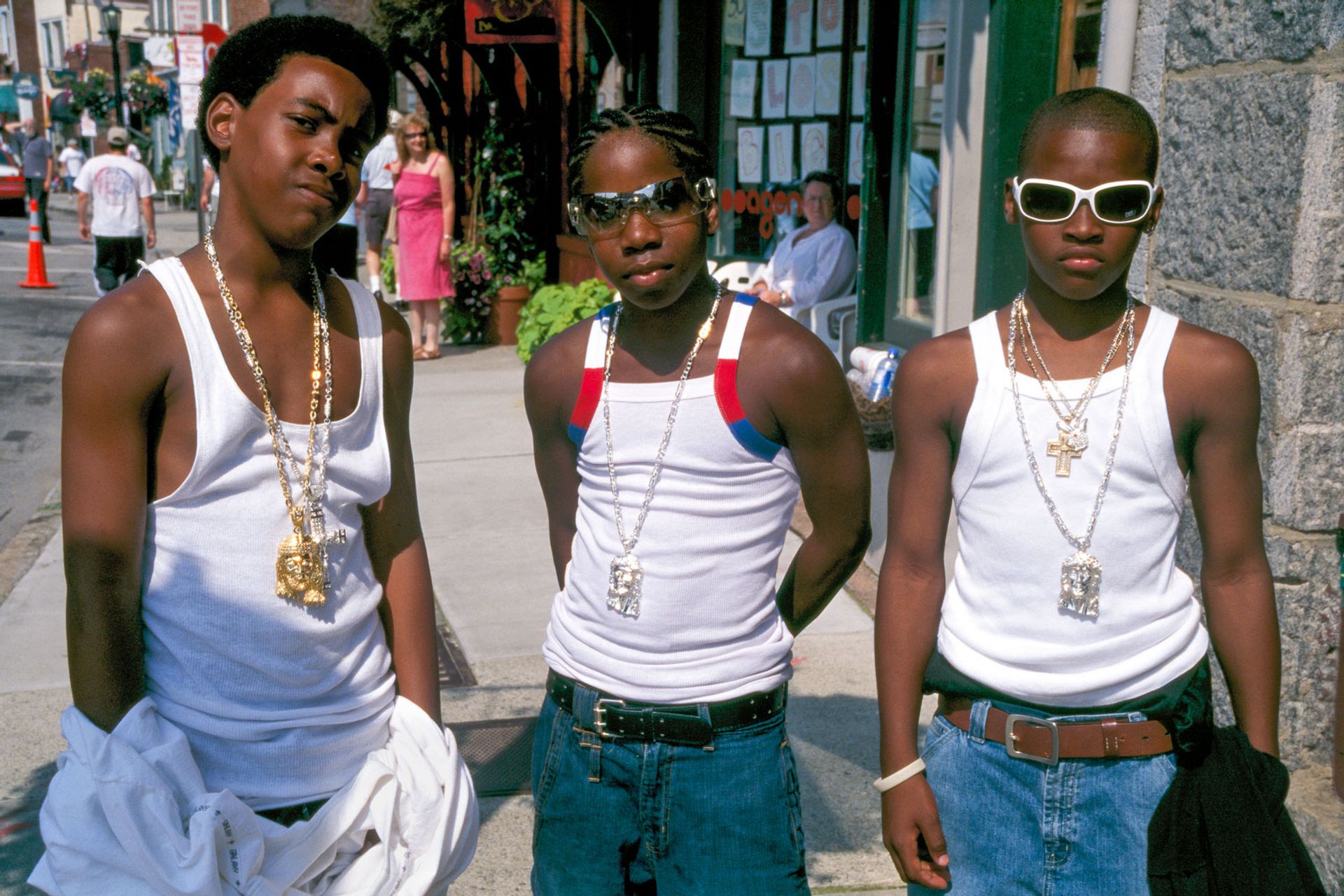

Photographs from the book:

Barkley L. Hendricks, Self Portrait (1977/2013) © Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Jack Shainman Gallery

Barkley L. Hendricks, Untitled (1986) © Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Jack Shainman Gallery

Barkley L. Hendricks, Untitled (1978) © Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Jack Shainman Gallery

Barkley L. Hendricks, Untitled (1988) © Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Jack Shainman Gallery

Barkley L. Hendricks, Bathtub Shopping Cart (1989/2013) © Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Jack Shainman Gallery

Barkley L. Hendricks, Sit, Stay (1978/2013) © Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Jack Shainman Gallery

Barkley L. Hendricks, Untitled (around 1995) © Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Jack Shainman Gallery

• Barkley L. Hendricks: Photography, Barkley Hendricks and Anna Arabindan-Kesson, Skira/Jack Shainman Gallery, 96pp, $25 (hb)