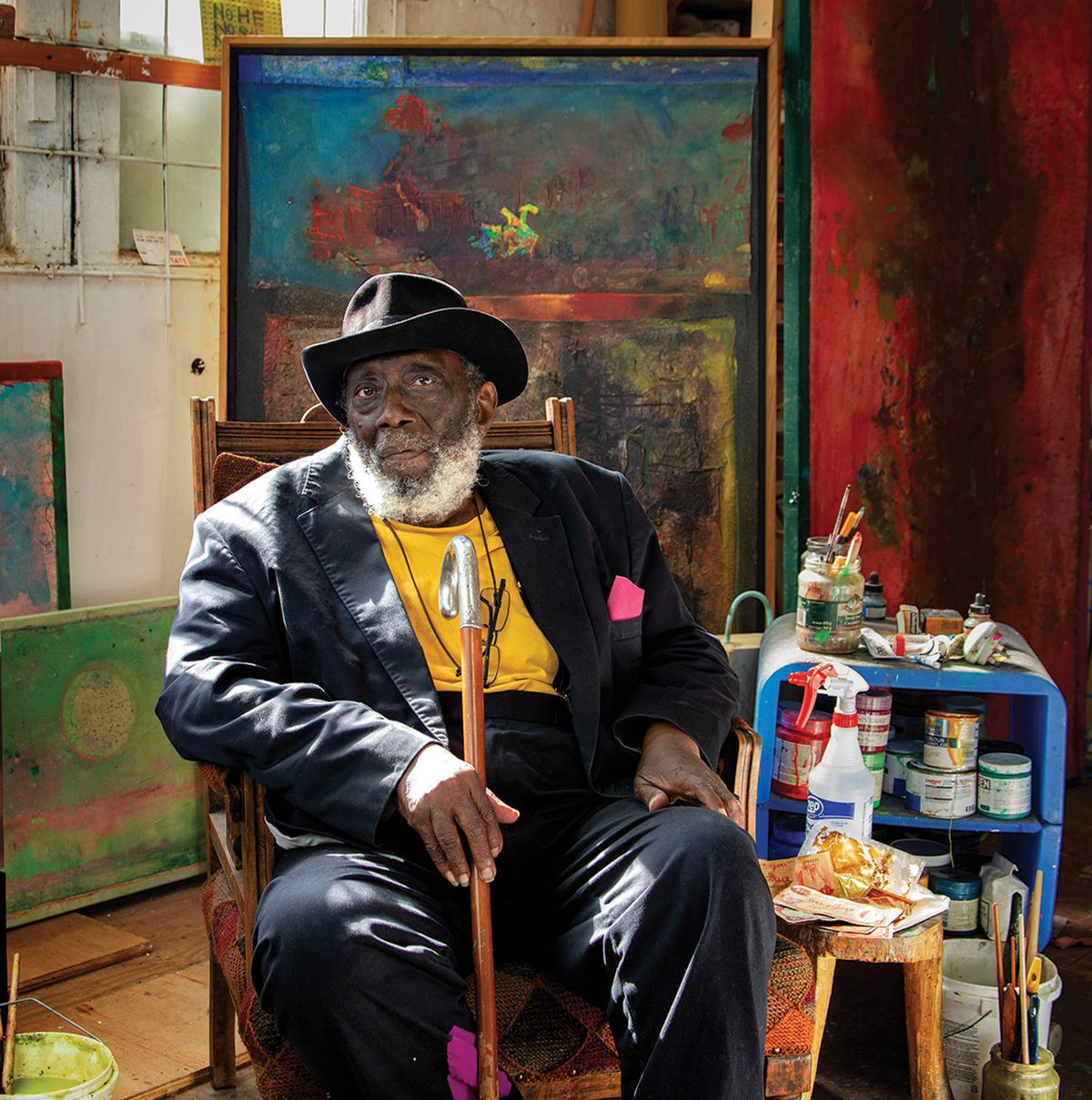

Frank Bowling has been experimenting with paint and extending the language of abstraction for more than six decades. Born in Guyana (then British Guiana) in 1934, he arrived in London in 1953 and won a scholarship to attend the Royal College of Art, from where he graduated in 1962 having been awarded the silver medal in painting (David Hockney was awarded the gold).

Bowling relocated to New York in 1966 and in 1971 had his first solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. There, he showed six of his Map Paintings, and shortly afterwards began to experiment with pouring, dripping and staining paint—and other substances—directly on to ever-more richly coloured and thickly textured canvases. He also worked as a journalist and editor at Arts Magazine during a period of intense debate around issues of Black art. He returned to London in 1975, and in 1990 took a loft studio in Dumbo, Brooklyn, and began to split his time equally between New York and London, maintaining a foot in both cities until 2018.

Despite his early successes, the Tate only acquired Bowling’s work in 1987—its first purchase of a Black British artist—and in 2005 he was the first Black artist elected to the Royal Academy. Tate held a retrospective of Bowling’s work in 2019. Now, recognising more than half a century of criss-crossing the Atlantic, Bowling’s inaugural show at Hauser & Wirth is taking place simultaneously in the gallery’s London and New York spaces. He also has an exhibition opening at the Arnolfini in Bristol on 3 July.

The Art Newspaper: You are showing simultaneously in London and New York. How do the two shows differ? What guided your selection of works for each location?

Frank Bowling: The show is curated by Hauser & Wirth; the idea was for it to be a single exhibition over two locations that focuses on my transatlantic journeyings over the past 60 years. It has turned out that the New York show is a kind of mini-retrospective, including Map Paintings and Pours from the 1970s, as well as paintings from every decade up to and including works I made last year. The London show mostly features works from the 1980s to today, and includes one of my recent favourites Swimmers (2020). They complement my exhibition opening in July at the Arnolfini in Bristol.

In 1966 you left London for New York—why did you make this move?

I first went to New York in 1961 on a travelling scholarship when I was still at the Royal College with Dave Hockney and Billy Apple. New York was the place where it was all happening. It was the frontline of artistic aspiration. In London it seemed that everyone was expecting me to paint some kind of protest art out of postcolonial discussion. For a while I fell for it. Clement Greenberg told me: “In America, there is no no-go area for anybody,” and I took him at his word. I found that my work was freed as my head was freed. He was a father figure and spotted that I was a natural colourist. It would be true to say that he watched over my anxious moving through from figuration to abstraction.

What was important about New York? Who did you meet, and what impact did it have?

I met artists, writers, theatre people. I was living in the Hotel Chelsea at first. So there were all kinds of people gathering there in the hotel bar, the El Quijote. I did visit with famous people like Andy Warhol, Franz Kline, Ken Noland, Jules Olitski and so on, and I used to spend time with Al Loving, Billy Williams, Danny Johnson and especially Jack Whitten. Larry Rivers was a close friend. Being around Abstract Expressionists and Colour Field painters expanded my horizons. A lot of Colour Field painting, like Rothko and de Staël, had the feeling of a heartbeat, of breathing freely, and at times being short of breath—much like the life one was living oneself, in colour.

In London I tended to look at the tragic side of human behaviour and tried to reflect that in my work, but gradually, as I became more involved in making paintings, I realised that the main ingredients are colour and geometry. And in New York, there was a lot of discussion among artists about how to get the materials to deliver all the expectations, all the emotions, truth, clarity. And I realised—boom! This is it. It’s about the material, not some sort of story. Gradually I decided to erase, say, the image of my mother and replace it with shape, colour and structure. I had a huge loft on Broadway that allowed me to experiment and make large-scale works. Moving to New York was a blessing; it gave me absolute freedom to work on my art.

You have said that if you hadn’t moved to New York, you would never have “got to grips with Black art—there would have been no way of doing it had I remained in London”. Why was this the case?

Terminology can be excluding. I don’t think there’s any such thing as “Black art”—I think Black people make good art. I’ve said before that art made by Black people is part of Modernism and should be seen in that light. My art is international. It’s a whole world thing—that’s what my painting is all about. I have always been frustrated about being pigeonholed as a Black artist, and the expectations people have around what the work should look like and be about. It was a new thing that was sprung on me in London. In order for people to feel comfortable, they have to put you in a box. I still insist that I’m not a “Black artist”. I’m an artist.

Swimmers (2020). Bowling’s art isn’t about politics, he says. “It’s about paint.” © Frank Bowling. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth Photo: Thomas Barratt

Until recently, you spent spring and autumn in Brooklyn, and summer and winter in London. Why was it important to work in both places?

I left London for New York in 1966, but my sons were all in England and I came back in 1975 as I knew I needed to be around for them. Coming back also meant I renewed my friendship with Rachel Scott, my wife. I’ve said before that, when I arrived in London in 1953, it felt like coming home. London was Turner’s town, and where I got acquainted with works by Constable and Gainsborough and the Old Masters that I discovered in the National and Tate galleries. So coming back to London in the 1970s also brought me back to that, and to the English landscape tradition.

I have to admit that I wanted to be in New York more than I was able to, but I lost my Broadway loft when I sublet it to an English fella who took it out from under me. Between 1975 and 1990, when I didn’t have my own place in New York, and I didn’t have representation in a commercial gallery in London, those were really tough, tough times. I had to rely on friends and family a lot.

Things really began to change in 1990, when I got a new loft in Dumbo, which at that time was a nearly derelict part of Brooklyn. One of my friends described it as being really rural—at that time there was nothing there, you couldn’t even get a cup of coffee, or groceries, or anything like that. It was either industrial or derelict.

So from 1990 is when Rachel and I started shuttling between New York and London. In some ways, having studios in both cities gave me the best of both worlds. In London, I was able to connect with my painterly roots in the English landscape tradition, taking on Constable and Turner, so to speak, and in New York I was engaging with Post-Painterly Abstraction, and the greats of American abstract painting. But in many ways, I was doing my own thing—trying to do work I felt was entirely new, trying to push the boundaries of what painting was about. So, I’d usually just pick up whatever I was working on at the time and pack it up into a tote bag, still wet, and carry it across the Atlantic. And at the other end, we’d roll it out and get going again, so the works were often made in both places.

You originally came to England from British Guiana with the intention of being a poet. What made you change that plan and decide to be a painter?

When I first came to England, I didn’t know anything about museums and art because I was trying to write. I felt that poetry was the best way to talk to myself, about myself. The first time I went to an art exhibition was when I stumbled across the Whitechapel Gallery, quite by chance. It was around 1956, when I was still in the RAF. I’d been in Brick Lane, buying stuff for my mother’s shop in New Amsterdam—buttons, lace, zips, that kind of thing—and I happened to walk past the Whitechapel when that show This is Tomorrow was on. I guess it was the start of Pop art, and I’d never seen anything like it before in my life. I had no idea that this stuff could be art.

What inspired me to make the move was that I felt, on being introduced to painting particularly, that I was using more of myself—I was using my body—to deliver the material onto the surface of the canvas. It seemed to be more all-encompassing than sitting at a desk with a blank piece of paper trying to deliver what you’re feeling and thinking.

Once I started, painting got a grip on me, so I just painted all the time. A blank canvas is much more inviting to me than a blank page; it became more engaging and satisfying than writing. Though I’m constantly scribbling this, that and the other. I play with words in the titles of my paintings using riddles and hints, because the paintings are there to deliver their own message, and if you can open a door to the content of the stuff on the surface, all the better.

You studied at the Royal College of Art with David Hockney and other artists at the core of British Pop art. But rather than make paintings of mass-produced goods and iconic figures, your work reflected global political tensions. Why was it important to have world events resonate through your work?

You could definitely call some of my paintings Pop art. There’s Cover Girl (1966), for example, and a few others from the 1960s that used magazine images, silkscreen images, stencils etc. And I was friends with people like Pete Blake, Dick Smith and so on. I was making a kind of expressionist version of Pop art. But I have always been more interested in the tragic side of human nature, and also conscious of what is going on in the world. I have always had a deep sense of the social injustice that’s out there. I’m upset by poverty, unfairness, the ravages of capitalism and the way people exploit each other. But my art isn’t about politics, it’s about paint. The subject of my art is paint—the way that colour washes, spreads, bleeds and runs across the canvas, and the way that paint-colour emits light.

Throughout your career—whether the early figurative paintings, the poured works, the Map paintings or later works where you apply different materials and embed objects into the surfaces—overriding everything has been a passion for paint itself, its materiality and its possibilities. What fuels this passion?

The possibilities of paint are never-ending. Use a brush, drip it, pour it—it moves around, it doesn’t sit still, there’s always an element of surprise. It’s deeply full of substance and potential. I let the material flow. I’ve been embedding this and that into canvases since the 1970s. I’m moved to chuck in detritus, and watch it swim and settle, it makes me feel I can get to a whole vision of what I’ve passed through in life.

Can you talk about how you set rules for yourself in your paintings, but then make a point of breaking them?

My painting is rules-based. As a teenager in New Amsterdam, I worked as a kind of an apprentice to my uncle who was a cabinet maker, so I learned all about how triangles and circles would fit within squares to make rock-solid furniture. I would always made my own frames. So, geometry is really important. Early in my artistic career I was part of a group learning about the chemistry of paint colour. I tend to start with geometry and a colour palette, both of which are all about rules, but then what happens to the paint when it’s on the canvas is something else. I don’t always try to control that and I’m always looking closely at how the pafint moves across the surface, always on the lookout for interesting accidents.

You have relentlessly experimented with methods and materials. Why is it so important to keep on the move?

Anxiety keeps me painting; I want to get better. I’m always risking things with the old procedures and processes, constantly trying to push it over the edge and looking for what will surprise me in the work. I won’t stop until I make the best painting in the world ever.

Texas Louise (1971) was featured in Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, an exhibition that focused on Black art in America from 1963 to 1983 © Frank Bowling. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth Photo: Thomas Barratt

Can you talk about the role of chance in your paintings?

Often I can’t sleep at night; I’m always thinking about what I’m going to be doing the next day. My mind’s always thinking about the work.

When I’m in bed at night, I’m making paintings on the ceiling, but it all happens very much in an extempore way. I mean, while I visualise it I don’t have any pre-planned idea about how I’m going to make a painting. I know what I’m doing, but chance always plays a role. I’m always trying to move into something more spontaneous—to make painting happen as if I didn’t do anything about it.

Your work often involves other people, visitors to your studio often pitch in to help make works and chance objects often end up in painting—it seems important that the process of making art, while serious, is also celebratory and fun.

I have a good time in my studio, that’s where it’s at, and it’s the only time of the day that I forget about the physical pain that comes with being my age. But I can’t do without family. I’ve tried to get them all nearby. Rachel, my wife, has been in the studio with me for decades, and now often Rachel’s daughters join me, and my sons and grandsons, to help out in the studio. When I’m in the studio I’m having a good time. My most happy times—aside from being in the studio—are when the children and grandchildren are around. And now even my great-grandson visits me in the studio. So yes, I’d agree, making art is celebratory and fun.

Biography

Born: 1934, Bartica, Guyana

Lives: London

Education: Royal College of Art, London, UK 1959-1962

Slade School of Fine Art, London, UK, 1960 (autumn term)

Key shows: 2019 Tate Britain, London; 2017 Haus de Kunst, Munich; Soul of a Nation, Tate Modern; 2006 Royal Academy, London; 1986 Serpentine Gallery, London; 1971 Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Represented by: Hauser & Wirth, London, New York, Zurich

• Frank Bowling: London/New York, Hauser & Wirth, London, until 31 July; Hauser & Wirth, New York, until 30 July. Frank Bowling: Land of Many Waters, Arnolfini, Bristol, UK, 3 July-26 September