How does Michael Armitage charge his paintings with such electricity? The Royal Academy’s new exhibition features just 15 of his works but their power is tangible. The show was organised by the Haus der Kunst in Munich, where the larger spaces allowed for 27 paintings, as well as drawings and lithographs. Alongside them were a group of 70 works by figurative East African artists, selected by Armitage in honour of their critical impact on his practice; there are 31 such works at the Academy. In London, the exhibition is scaled down, then, but not diminished—the three galleries resound with ample Mwili, Akili na Roho or “Body, Mind and Spirit”, as the East African section is called.

All of Armitage’s paintings here are made on lubugo bark, a material that he discovered in a tourist market in Nairobi when he was looking for an alternative to the freighted history of working oil paint into the tooth of stretched canvas. For an artist who was born in Kenya but trained in very traditional British settings—first at the Slade School of Fine Art and then at the Royal Academy Schools—you can see why a distinctly East African textile would appeal, with all the vitality of its imperfections. The fibrous grain of the cloth, scarred with the seams where patches have been stitched together, energises his compositions, much as the crackling of a stylus skipping over specks of dust on a record might make for livelier listening.

Michael Armitage, The Paradise Edict (2019) © Michael Armitage. Photo: © White Cube (Theo Christelis)

Armitage spent years figuring out how to work on bark cloth, finding that his paint needed to be thinned down, for instance, to retain the “graphic clarity” of his imagery. The material is made by people of the Baganda tribe, by beating sodden strips of the inner bark of a ficus tree; it has a ceremonial status and is often used as a death shroud.

What does it mean to paint onto a support intended to carry a body into the afterlife? The question feels significant given the exhibition’s title, Paradise Edict, a strange coupling of words, suggesting an exhortation (get thee to Eden) or perhaps a command issued from the Promised Land. Do the characters in these paintings belong to this world or the next? Depicted in a blaze of colour, arrested in motion, they seem to me like Milton’s fallen beings, “Hurl’d headlong flaming from th’ethereal sky”.

Intoxicating colours

The word “seductive” often accompanies descriptions of Armitage’s painting and there is just so much to lure the eye: the palimpsest of figures drifting in and out of the field of paint as if in a dream or reverie; the intoxicating colours—passages of chalky blue, accented by neon pink with a bass line of verdant green; and the sheer character of expressions, caught with seeming ease. Sometimes the figures are fleshed out and sometimes they are just loose clusters of marks, but always the weight of their bodies feels real. Look at the intimacy of the infant who leans into his crouching mother in Mydas, the balletic wrist of the airborne figure at the heart of The Accomplice, or the heft of the man pushing his cart in Mkokoteni (all 2019).

But that does not entirely account for the seduction. These are paintings critically engaged with how a country such as Kenya is portrayed by, for and to its people—paintings questioning the devastating legacies of colonialism and the continuing occidental fetish for exoticising African cultures. Armitage’s colour palette is self-consciously redolent of the spice of Tangier for Matisse or Tahiti for Gauguin. Animals recur, most frequently monkeys, as symbols of mischief as well as evocations of racist stereotypes of Black men. In Baboon (2016), our protagonist lies languidly on one elbow, a bunch of bananas covering his crotch in a parody of human modesty; in Sheath (2016), a monkey’s face morphs into concentric labial forms. These references seem to probe the persistent sexualising of the other, as well as the exertion of dominance by colonial powers in their plundering of colonies.

Gallery view of Michael Armitage Paradise Edict at Royal Academy of Arts. Photo: © David Parry/ Royal Academy of Arts

Some of Armitage’s paintings have the additional bite of recent political events. Hornbill (21st-24th September 2013) (2014), which was on show in Munich but not in London, features one of four terrorists responsible for the Westgate shopping mall attack in Nairobi, in which 67 people were shot dead. The first paintings at the Royal Academy were made after Armitage joined the crew of the K24 news channel at an opposition rally following the 2017 Kenyan elections, at which dark, carnivalesque scenes unfolded as protestors dressed in wigs and masks were violently dispersed by teargas and gunfire. I felt mesmerised by the man in the lower right of Pathos and the Twilight of the Idle (2019), remembering how Armitage once quoted Walter Sickert on his idea of “a page torn from the book of life”; there is so much painterly truth to this man that he had to have been witnessed, his necklace of fur like an Elizabethan ruff and face grimaced to release a sound that looks caught between song and scream.

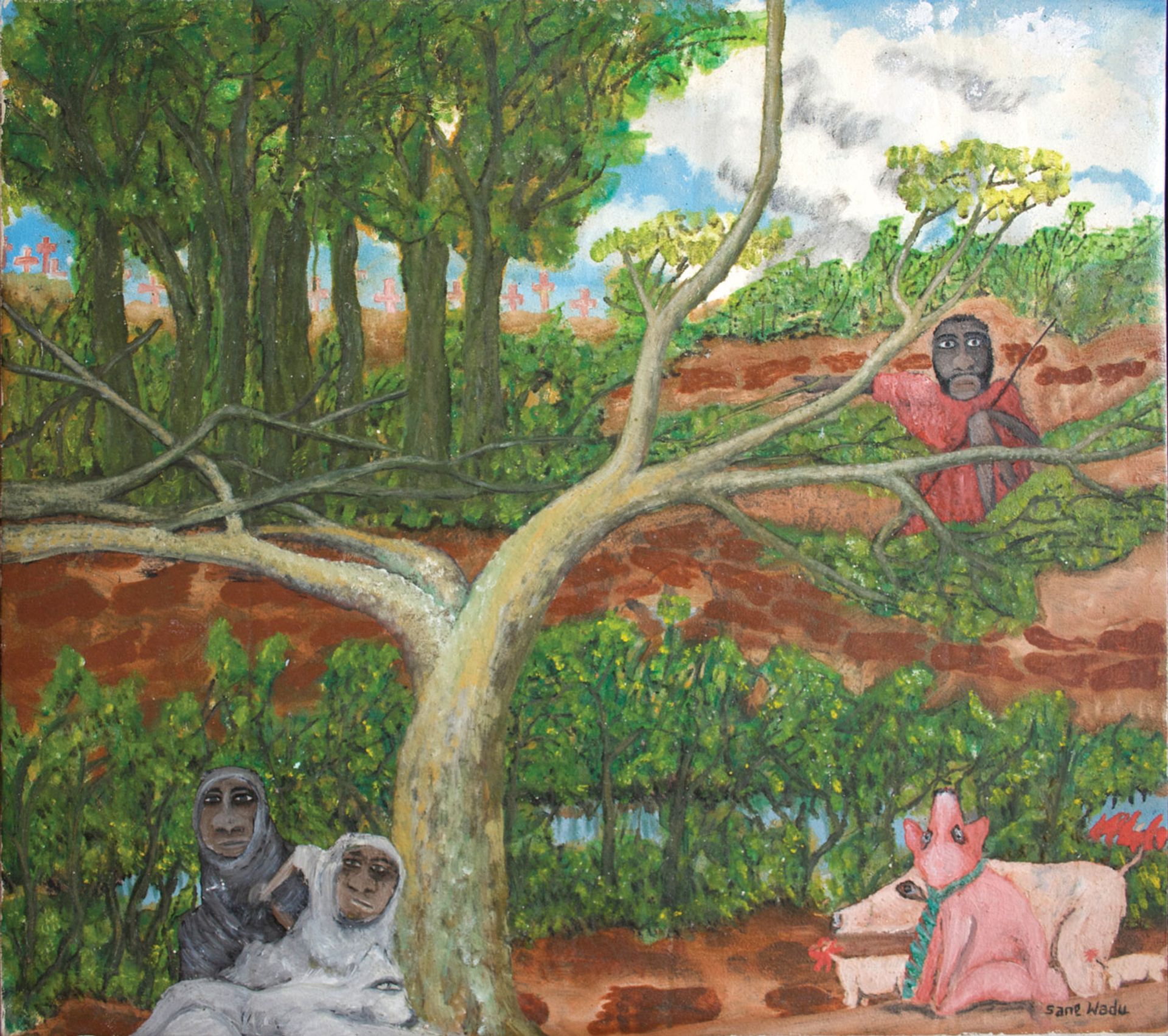

The selection of work by East African artists allows Armitage to firmly root himself within a non-European Modernist tradition. In the gallery, this work is hung in its own space, although the catalogue interweaves the artists in a way that allows for their synchronicities to be felt more keenly. Look at the bands of watery blue cascading into yellow in Elimo Njau’s Dream Landscape of 1968 and you can see the connection to the play of density in Armitage’s lush, vegetative background in the eponymous Paradise Edict (2019). The work of Jak Katarikawe, a largely self-taught artist born in south-west Uganda, has a similar intensity of colour and form, while Asaph Ng’ethe Macua’s work matches Armitage in the ferocity of expression and magical realist tone. Scanning through the titles of these works—The Garden of Eden, Genesis, Chapter 2; Eve; Abraham and Isaac—also reveals the shared fascination with the intersection between African mythology and Christian iconography.

Armitage has devoted a gallery in the show to East African artists who have influenced him, such as Sane Wadu, whose My Life 1980-1990 is shown here © The artist

Some in the art world may feel that they have had a great deal of exposure to Armitage in recent years: his exhibition at the White Cube in 2015, at the South London Gallery in 2017, his inclusion in the Venice Biennale in 2019, his project space in the reopened Museum of Modern Art later that year and his inclusion in innumerable international group shows, including Radical Figures at the Whitechapel Gallery in 2020—although I sense that he has been conscientious about avoiding overlap between the selection at the Royal Academy and that of recent London shows. Critical attention of this level is unusual just over a decade after an artist has graduated, even given the current trend for narrative painting, but to me it feels both welcome and deserved. These are complex, lyrical works that are time-consuming to make and warrant the kind of slow looking that gains with each fresh encounter.

So go and see this exhibition and then go and see it again. After a year in which so many of us have felt glazed by our relentless exposure to screens, the charge Armitage delivers is just the reboot we need—the electricity of painting torn straight from the book of life.

Paradise Edict, until 19 September

Curators // Anna Schneider, Haus der Kunst, Anna Ferrari, Royal Academy of Arts

• Eleanor Nairne is a curator at the Barbican Art Gallery, London. She organised the current show Jean Dubuffet: Brutal Beauty