“Different group shows have different origin points, this one has a double origin point,” says the curator Helen Molesworth, who has organised the show Feedback (5 June-30 October 2021), at the New York dealer Jack Shainman’s upstate outpost The School, in Kinderhook. The exhibition takes its name from a 2004 work by Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller, which is included in the exhibition along with works by 22 other artists that play on the reverberations of personal memory and American mythology.

“I had the Cardiff/Miller piece Feedback knocking around in the back of my head for years. It was like a pebble in my shoe,” Molesworth says. “When Jack asked if I wanted to do a show at The School I said sure, but I wanted to go see it first.” As its name implies, the satellite space is an early 20th-century high school, built on a five-acre lot in 1929, which the dealer converted into a year-round 30,000sq. ft gallery in 2013. “I went and I had what I describe as a kind of auditory hallucination. Walking into the building, I felt overwhelmed by the sound of kids. I remembered the din of my big public high school in Manhattan with 4,000 kids in the building, so between that and the Janet Cardiff piece, I knew there was a show, and I started working from there.”

The Cardiff/Miller work consists of a large Marshall amplifier and a wah-wah distortion pedal. When viewers step on the pedal, the Star Spangled Banner, performed in the style of Jimi Hendrix’s famous Woodstock rendition, blares from the amp. “I love the complexity of what it means to appropriate that piece of music, and to engage with it physically as a viewer,” Molesworth says. “For me, it encapsulates my feelings about what it means to be American. I love it, I am it, but I hate it too. There's something about that version, and it's virtuosity, that also makes it feel like art—the complexity of it all.”

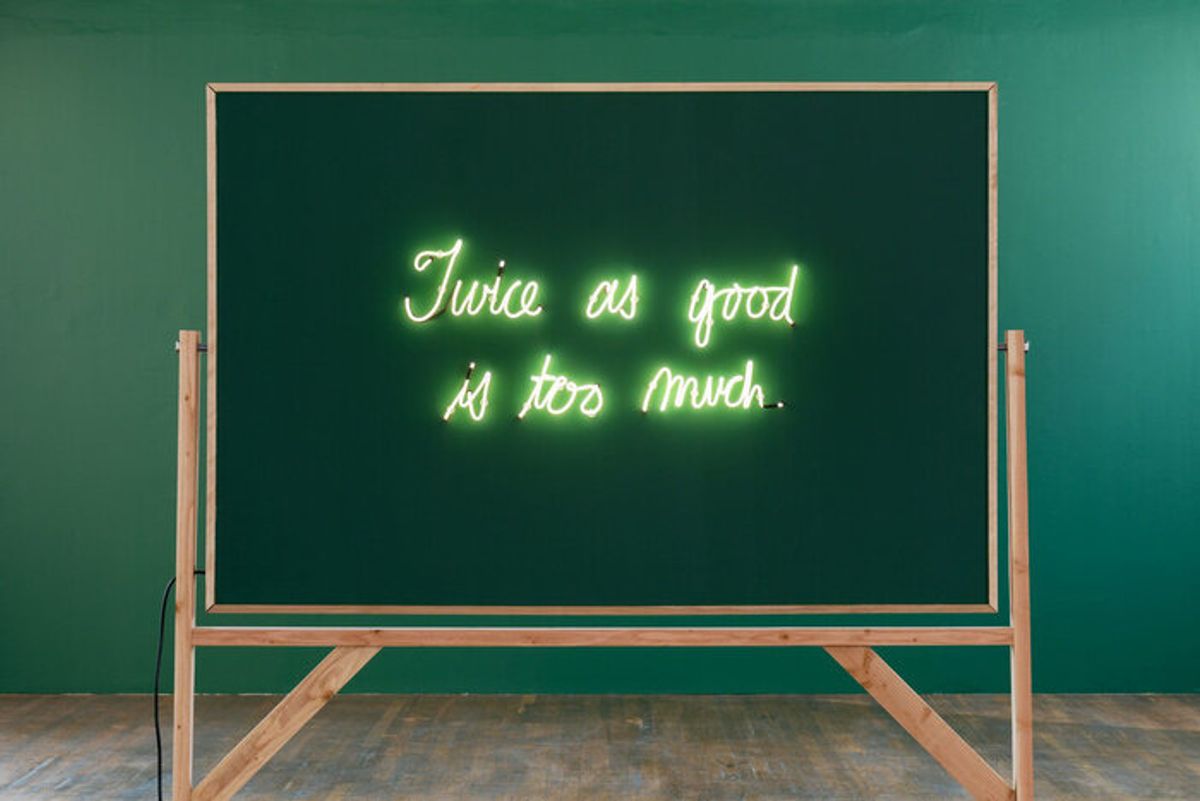

The show includes works by artists such as Sanford Biggers, Karon Davis, Rose B Simpson, and Cauleen Smith that pick at the complexity of American culture and history in a similiar manner. “Like many white people, I've spent the last 20 years realising that so much of what I learned in school omitted so much that it might not even be considered true,” Molesworth says. “If that doesn't stand the test of time, I was considering what does.”

The exhibition was originally due to open in May of 2020, while the US was still under the deep shadow of the Trump administration and a tense uncertainty about the 2020 presidential election permeated many Americans’ daily lives, but was postponed for a year when the coronavirus hit. “I had a total moment of crisis, thinking we should scrap the whole show, since it was originally designed to go up the summer before the election,” Molesworth says, “but then I thought about it and realised that everything is exactly the same. I don't mean that in a cynical way, I'm not saying that things can never change or that the events of the past year have not pushed certain conversations into places where they were very much needed. But the kinds of ideas that artists are dealing with in the show are ideas that my curatorial practice has been involved with for years, so I decided to stay the course.”