The Tulsa Race Massacre, a historic example of domestic terrorism in which mobs of white men murdered and injured countless Black citizens and burned down Black-owned businesses in the city’s Greenwood District, has been little studied until recently. This month marks 100 years since the two-day riot, which has been described by contemporary historians as the “single worst incident of racial violence” in the US, and artists and institutions are recognising the event and its fallout through displays and projects.

Most significantly, an expansive history museum memorialising the massacre opens for previews on 2 June in Greenwood. The $18.2m centre, titled Greenwood Rising, is in the final stages of construction and will include permanent installations and archival materials that aim to “contextualise the history of the community and its founders, and the trials and tribulations they encountered due to the racial injustice”, says L’Rai Arthur-Mensah, the director of the New York-based design studio Local Projects, which oversaw the exhibition concept for the museum.

The new museum seeks to “provide visitors with a space to have dialogue around the work that it takes to move toward racial reconciliation”, Arthur-Mensah says. This will include a room featuring an immersive installation that recreates the sounds and scenes of the riot (which visitors can avoid if they find too distressing). The museum has been funded through the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission, an arts, tourism and economic development committee chaired by the Oklahoma senator Kevin Matthews. “It takes courage to be transparent about our history, including both famous and infamous events,” Matthews said in a statement. “We must address and discuss the facts as they have happened so we can ultimately stand together across racial, geographical, political and cultural lines.”

The artist Jimmy Friday views his reflection in his installation Greenwood: Black Wall Street, part of the Greenwood Art Project Photo: Marlon Hall

Meanwhile, the Greenwood Art Project, a city-wide public art initiative supported by Bloomberg Philanthropies, launched earlier this year with a procession led by artist Yielbonzie Johnson through the former business hub in Greenwood. Johnson and fellow artist Katherine Mitchell also installed conceptual works in two churches in Tulsa that are meant to remain on view permanently. In the coming months, the initiative will realise around 30 commissions, including performances, interactive works and public art. Among them is a large outdoor clay sculpture by Myiesha Gordon Beales that will be fired over two days in an open-air bonfire, and will then be painted by community volunteers.

CNN Films is also releasing the documentary Dreamland: the Burning of Black Wall Street, which deals with the erasure of the massacre from history books, an intentional act led by white politicians, and the mass graves that have come to light as archaeologists excavate sites around the city. Although the total death toll of the riot is uncertain, experts believe that between 100 to 300 bodies of Black victims were dumped in unmarked graves.

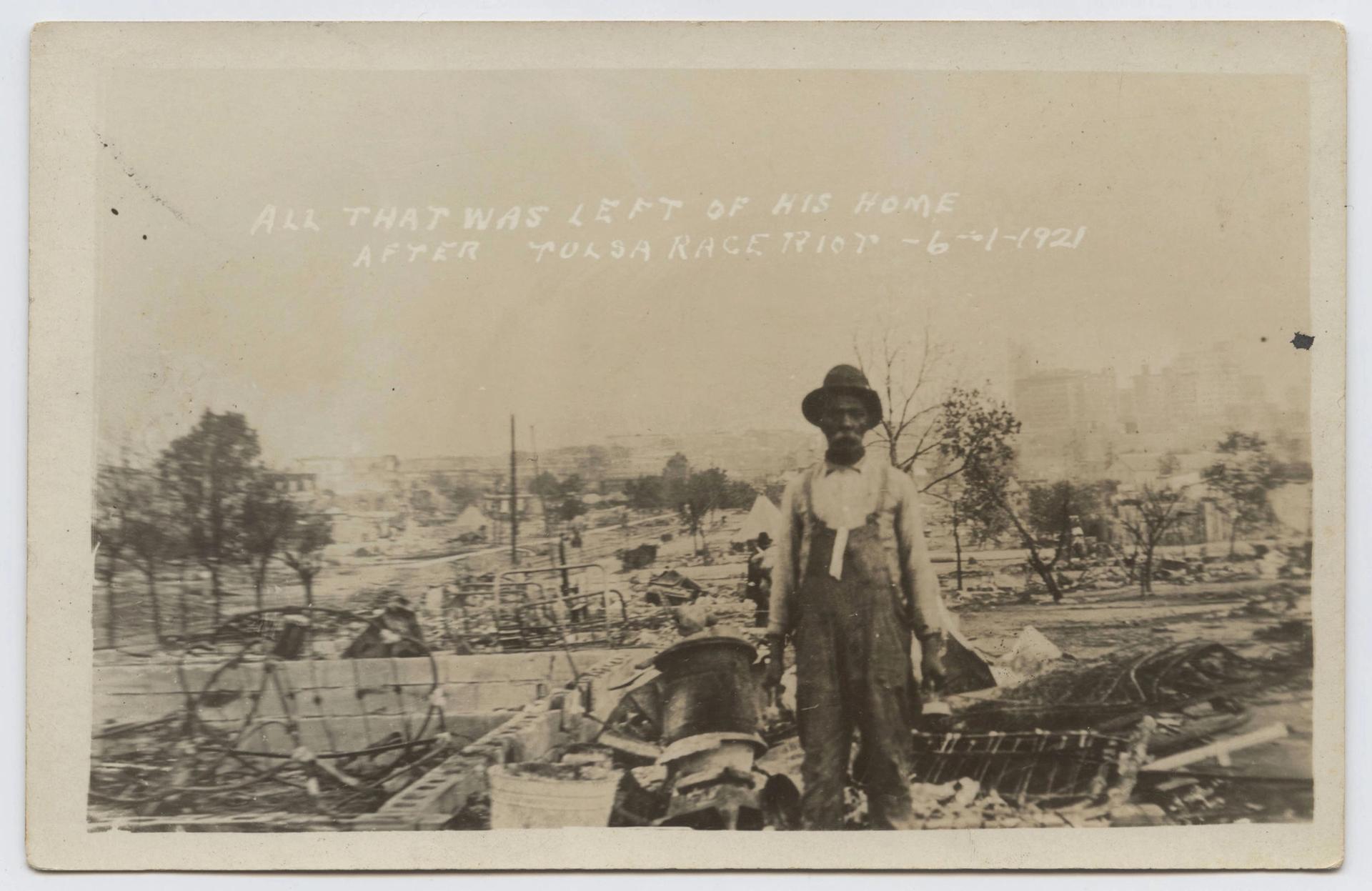

"All That Was Left of His Home after the Tulsa Race Riot", 1 June 1921 Greenwood District, Tulsa, Oklahoma Digital Collection Photo: DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University

The film also also underscores the racial tension between Black, white and Indigenous people in Tulsa, delving into an even lesser-known facet of American history, when some Indigenous tribes owned Black slaves as a means to assimilate into white society. Tribes that populated Oklahoma in the 1800s, including the Chickasaw, Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole, brought enslaved people with them on the Trail of Tears west when President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act in 1830.

And, through a $300,000 federal grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, the Gilcrease Museum is now digitising a collection of more than 600 archival items—including photographs, newspaper clippings, audio recordings and other materials—from the family of the historian and activist Eddie Faye Gates. Gates was commissioned by the city to research the massacre, and later advocated for reparations for survivors. “We’re exploring what wisdom and knowledge we can extract from what Gates so diligently preserved,” says Autumn Brown, the lead researcher for the project.

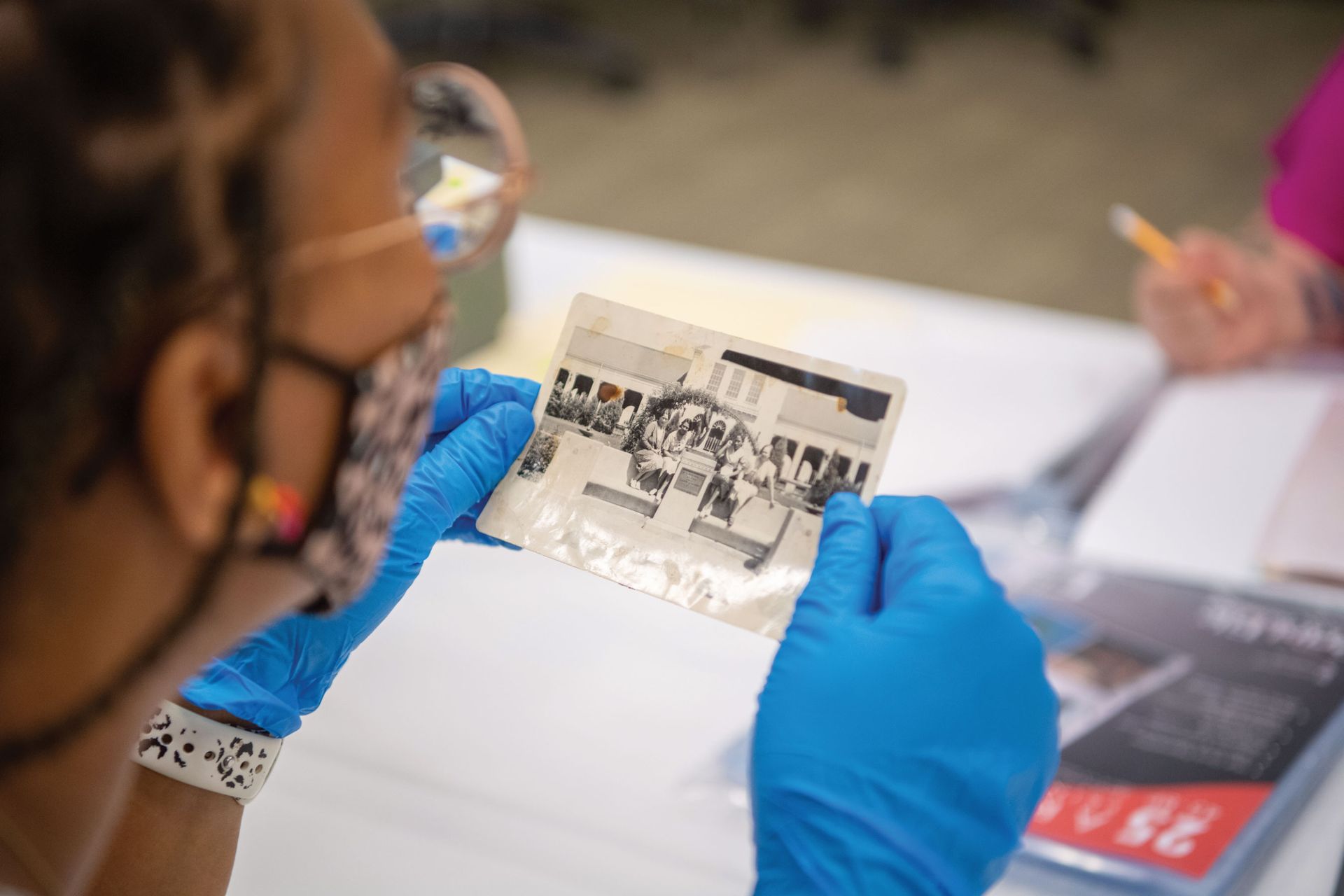

Autumn Brown, IMLS Research Scholar, working with the Gilcrease Museum’s Eddie Faye Gates Archive Courtesy of the Gilcrease Museum

Other projects in Tulsa will focus specifically on the present day. The Philbrook Museum is hosting the exhibition Views of Greenwood (until 5 September) which illustrates how businesses and residents in the area have rebuilt and thrived after the earlier devastation. The show features photographs taken over the past five decades by the artists Don Thompson, Gaylord Oscar Herron and Eyakem Gulilat.

The three living survivors of the massacre, Viola Fletcher, Leslie Randle and Hughes Van Ellis, testified at a civil rights congressional hearing in Washington, DC, last month, calling for restitution for survivors and descendants. Fletcher, who was six at the time of the riot, told the committee: “I will never forget the violence of the white mob when we left our home. I still see Black men being shot, Black bodies lying in the street, and I still smell smoke and see fire.”