Tair Salakhov, one of the most famous artists of the cultural thaw under Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev during the 1950s and 1960s, has died aged 92. His daughter, the artist Aidan Salakhova, told Russian press that he passed away from pneumonia in a Berlin clinic on 21 May.

Salakhov’s biography and persona spanned the Soviet era with cinematic sweep. He was born in Baku, Azerbaijan to a Soviet party official who was arrested in 1937 during Stalin’s Great Terror regime and later executed, which his family learned only in 1956 after Khrushchev’s denunciation of his predecessor.

He graduated from art school in Baku and then from Moscow’s Surikov Art Institute and became one of the leading figures of the post-war Severe Style art movement, which was influenced by Russian avant-garde and Western art, and turned away from the Socialist Realist style enforced under Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin.

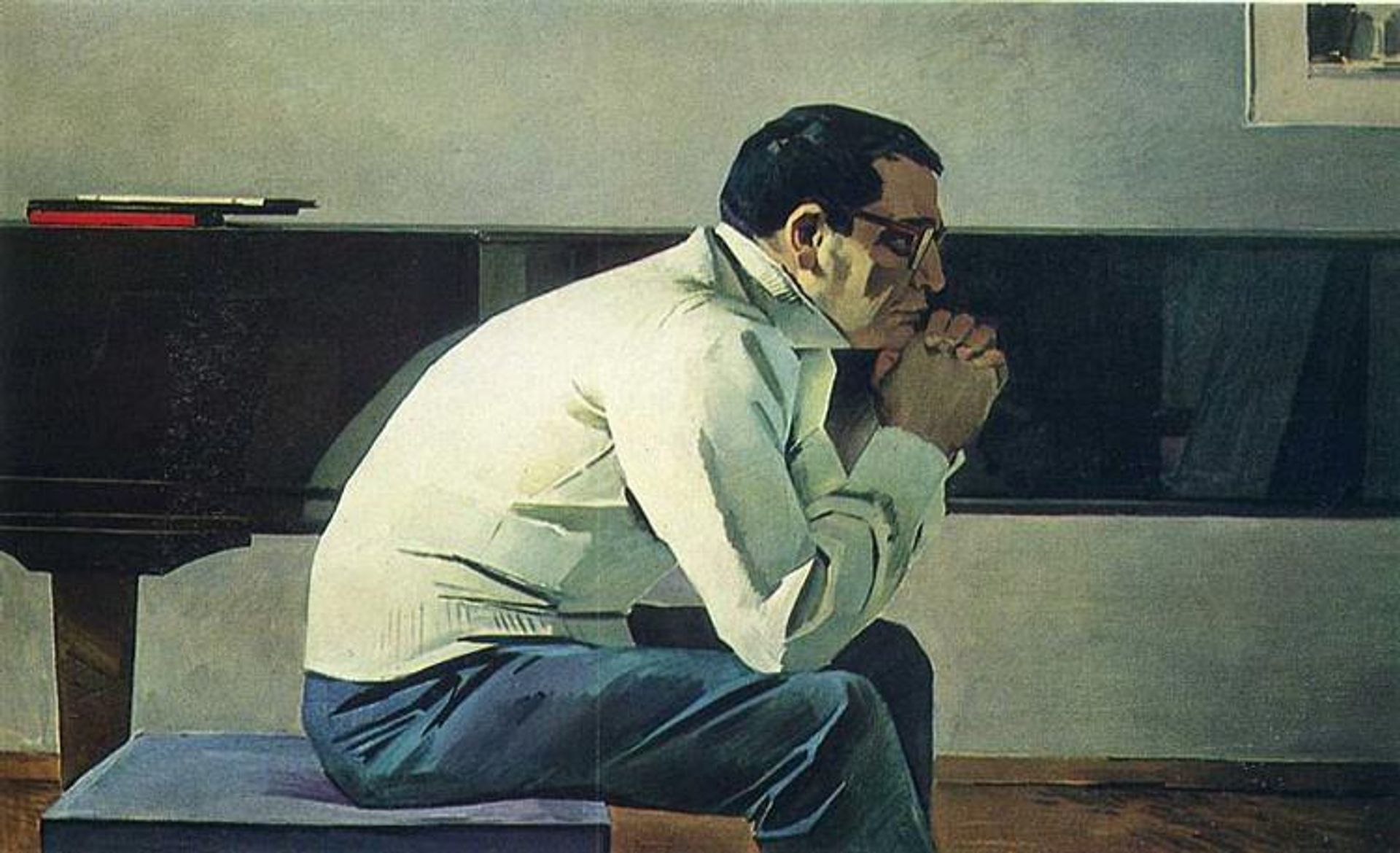

Tair Salahov's Portrait of Composer Kara Karaev (1960)

Among Salakhov’s most striking works are paintings depicting oil workers in Baku, a centre of the industry, and portraits of Soviet cultural figures. His Portrait of the Composer Kara Karaev (1960) from the collection of the State Tretyakov Gallery was among approximately 250 artworks chosen for the Russia! exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in 2005.

Another of his most recognisable works is a portrait of his daughter Aidan as a child on a rocking horse. The original, painted in 1967, is also in the Tretyakov’s collection. A version that he painted for a 1980 exhibition at Gekkoso Gallery in Tokyo sold for £269,000 at Sotheby’s in 2015.

Salakhov also taught art for decades, first in Baku, then Moscow, at the Surikov Institute.

He became a powerful figure on the Soviet art scene as first secretary of the Union of Artists of the USSR and later the vice president of the Russian Academy of Arts. Salakhov used his posts to defend artists who were often under ideological attack. And during Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika he facilitated exhibitions by Western artists previously shut out of the USSR, such as Francis Bacon and Robert Rauschenberg.

Tair Salakhov with his daughter the artist Aidan Salakhova / Facebook

“These artists were completely unknown here,” he told the Russian arts publication Artguide in 2013. “Until the 1950s there was an unspoken ban on Cézanne and the Impressionists, which was later lifted, but the contemporary art of capitalist countries remained closed to viewers.” He described how Rauschenberg, with whom he ended up becoming friends, asked the Union of Artists to help organise his exhibition in the USSR. “I always tried to remain open to any offers, and if necessary, took responsibility.

Salakhov’s support for his daughter Aidan, one of the pioneers of the post-Soviet contemporary art scene, meant that “he became in some sense the father of new Russian art as well,” The Art Newspaper Russia reports.