The Depression-era Works Progress Administration murals of Victor Arnautoff, a Russian émigré artist who had worked with the Mexican painter Diego Rivera, brought him wide acclaim in San Francisco in the 1930s. In 2019, his name resurfaced there amid controversy when a school board voted to cover up his mural about the life of George Washington because of his depictions of downtrodden slaves and a Native American.

But little is known in the West about the mosaics that Arnautoff created after his return in 1963 to Mariupol, his Ukrainian hometown, by then a Soviet industrial and resort city. As Soviet-era monuments, they have been threatened with destruction and neglect as part of a “decommunisation” campaign that started with the toppling of monuments to Lenin after the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union and the advent of Ukrainian independence.

Ivan Stanislavsky, a journalist and photographer who is studying large Soviet mosaics in Mariupol, says the state of such works ranges from “nearly ideal to catastrophic”. Some are “slowly crumbling, piece by piece”, such as Arnautoff’s first work in the city, Conquerors of the Cosmos from 1964, on an unprotected wall of a postal building. The mural depicts space scientists and includes a hammer and sickle motif.

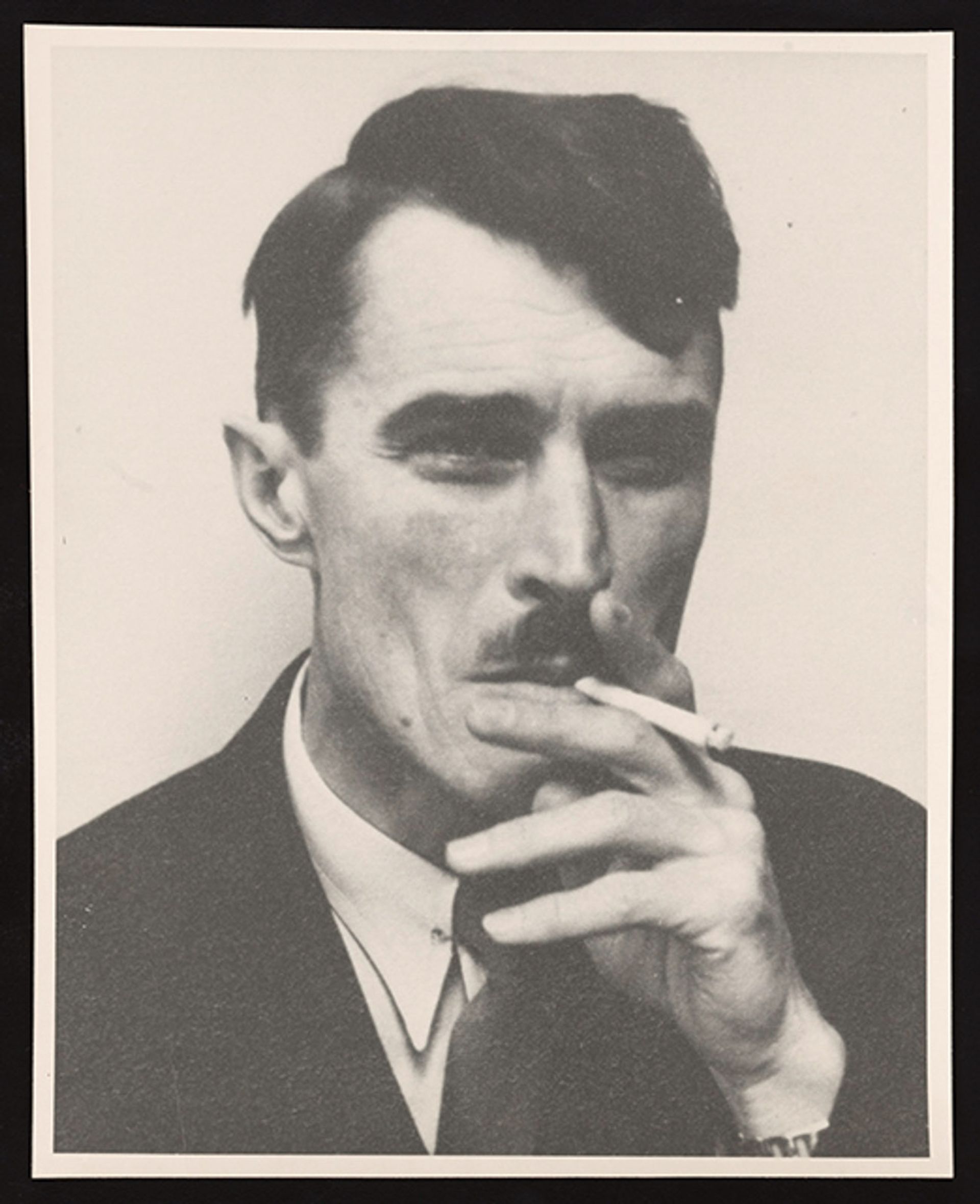

Arnautoff worked with Diego Rivera in the 1930s, and his murals brought him wide acclaim in the US Courtesy of the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

The mosaic was pioneering in its use of ceramic materials and measured over 100 sq. m, Stanislavsky says. Oleksandr Chernov, an art historian who co-authored a book with Stanislavsky on monumental mosaics created in Mariupol from the 1960s to the 1980s, says that while the top section of Conquerors of the Cosmos is “already lost”, it could be restored by using old photographs and postcards as source material. Artists have offered to do this, but the authorities have not responded, he says.

The two other surviving mosaics in Mariupol executed primarily by Arnautoff are Teacher with a Group of Children (1965), mounted on the exterior of a school, with the students depicted wearing Soviet-era red scarves, and From the Scythians to the Cosmos (1968-70), a visual history of the Azov region created for the city’s airport, with 78 figures on 26 themes. The latter also includes Soviet symbols and is well preserved, although the airport has been off limits to the public since being requisitioned by the Ukrainian military in 2014, says Zhenya Molyar, who was a curator at the Izolyatsia Foundation’s Soviet Mosaics in Ukraine project. That initiative relies on contributions from activists in Ukraine, often young people who have become vocal about the significance of art created in the Soviet era, says Molyar, who continues to study and promote the mosaics.

A tragic period

“We are trying to position this as art, and it reflects a tragic period,” Molyar says. “They are Ukrainian artists who created in Ukraine. They lived in a situation when they couldn’t avoid reflecting what was Soviet. Of course some were ideological, others were secretly anti-Soviet, others just wanted to make money. We can analyse this only when we make sense of who did what, why and how. The main thing now is to preserve the works.”

Teacher with a Group of Children (1965), mounted on the side of a school © Ivan Stanislavsky

Arnautoff’s work in the US from the 1920s to the 1960s, and his decision to return to the Soviet Union, are documented in detail in Victor Arnautoff and the Politics of Art, a 2017 book by Robert W. Cherny, a professor emeritus at San Francisco State University. Born in 1896, the artist attended school in Mariupol and fought in the White Army against the Bolsheviks. After working with Rivera during a sojourn in Mexico, he developed Communist sympathies, which later led to an unsuccessful effort to push him out of a teaching position at Stanford University.

Greeted with some privileges upon his return to Ukraine, he was denounced by others as “a White Russian henchman”, Chernov says, and eventually left for Leningrad, where he died in 1979. Arnautoff’s stepson, Sergei Betekhtin, says the artist was under humiliating KGB surveillance. Lubava Illyenko, an art historian who works on Izolyatsia’s project while writing a dissertation on Ukraine’s mosaics, says that from today’s perspective, Arnautoff “adhered too closely to the official method of Soviet art, Socialist Realism”, but she believes his works should be preserved.

“The question of history is one of constant manipulation,” in both the former Soviet Union and in the US, with Arnautoff a case in point, Illyenko says. “Today the Soviet star is attacked because that corresponds to our politics. Tomorrow it will be something else.”