Something I’ve learned from virtual events during the pandemic is that talking about art on Zoom is a challenge. The best thing to do is focus on the lives of the artists themselves. For a HistFest panel on Artemisia Gentileschi I recently spoke at there was no shortage of tales to tell, but I did allow myself two visual aids, both books. The first was Ernst Gombrich’s The Story of Art, the most successful art history book ever published. But in 600 pages spanning over 12,000 years, there is just one female artist (Käthe Kollwitz). My second was Chris Petteys’s Dictionary of Women Artists, which has more than 21,000 entries.

This discrepancy is embarrassing for art history. It never ceases to amaze me that an artist as talented as Artemisia could be so comprehensively forgotten for over 300 years. Despite decades of revisionism by feminist art historians, art history still seems to be afflicted by a structural sexism. It is apparent not just in the way the canon has been shaped by men, but in the methods we still use to judge what is and is not “good” in art. Artemisia’s entry in the Grove Dictionary of Art, for example, suggests that “the heavy build of her figures” demonstrates her “lack of conventional training”. An alternative assessment might herald the moment a woman decided to paint women without the gym-thin implausibility of classical models.

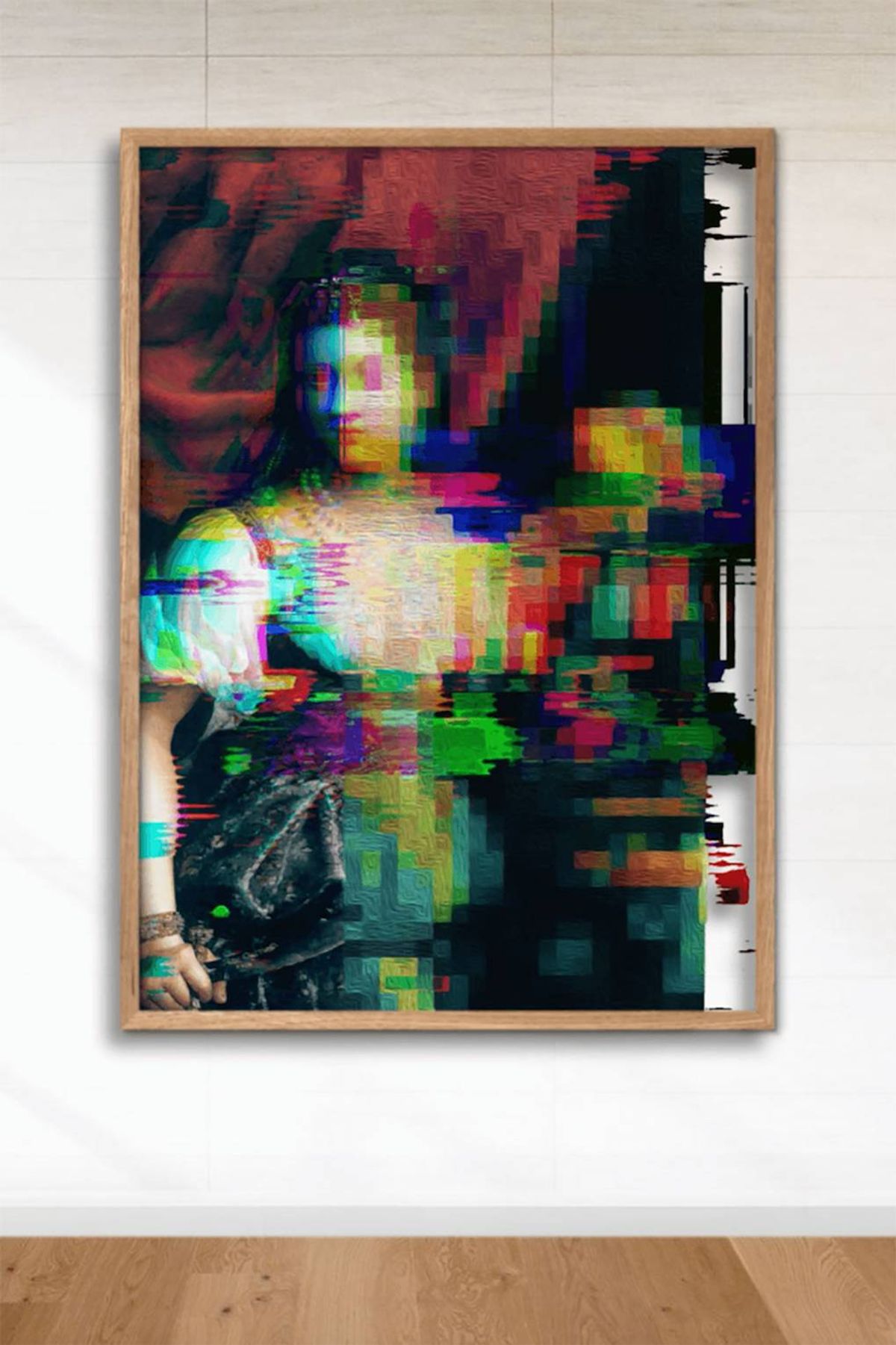

For centuries, audiences have been conditioned to assume that the best art is made by Western men, a fact also reflected by the art market; today’s two most valuable living artists are Jeff Koons (most expensive work: $91m), and David Hockney ($90m). Jenny Saville is the most expensive female artist, but some way behind in the rankings at $12.4m. There is, then, a sad inevitability about the art market deciding that the “best” and (at $69m) most valuable artist of the latest craze, digital art sold as NFTs, should be a Western male called Mike Winkelman, aka Beeple.

Will Beeple’s fame and value last? At this point I would normally say, portentously, “wait for the verdict of art history”. What a small number of players in the art market get excited about is often not a reliable indicator of artistic longevity. But as we have seen, art history isn’t necessarily equipped to give us an objective view of what will stand the test of time; it has an in-built bias towards Western men.

All of which gives the “tokenisation” aspect of the NFT market—where the buyer of an NFT then divides it up into smaller slices, to be sold as tokens—an unanticipated art historical relevance. For the first time, we can see in real time if the popularity of an artist who makes tens of millions in one auction at Christie’s is based on more than the whims of a few very rich people. When, in January, the buyer of 20 Beeple works titled Everydays tokenised the virtual museum in which the works of art are now housed, called B20, the price of the initial offering was $0.36. When Christie’s announced and promoted the sale of Beeple’s Everydays: The First 5,000 Days sale, endorsing Beeple as the new Mozart of digital art, the price rose to a high of $28. With the record $69m bid at Christie’s, it seemed Beeple’s market status was assured. Now, however, the price of a B20 token has fallen to $1.26.

Few of us will begrudge Beeple his financial success. But if more of us recognise the biases that help shape his success, we might not have to wait 300 years to find the digital age’s own Artemisia.