As museums in England reopen their doors to the public this month, it is fitting that the Hepworth Wakefield—which celebrates its tenth anniversary on 21 May—is doing so with a major exhibition of Barbara Hepworth, an artist for whom physical encounters with art were so vital.

The Wakefield-born and raised sculptor, whose rich and varied career stretched from the 1920s until her death in 1975, believed sculpture not only shapes our understanding of the world but also influences the way we hold ourselves within it. “She was sensitive to the materials she used—the bright bronzes, the polished wood, the different stones—and to the way objects encourage you to move around and activate your body,” says the museum’s curator, Eleanor Clayton.

One of Hepworth's early stone sculptures, Mother and Child (1934) © Bowness, Hepworth Estate

Whenever there is a major exhibition of an artist such as Hepworth, competing concerns crop up: do you provide an overview for those who might not be familiar with her, or focus on some of the lesser known aspects of her work? “We’re lucky we haven’t had to make those either-or decisions,” says Clayton, explaining that, since the whole museum could be given over to the show, she is doing both.

The exhibition will trace the artist’s career from the early abstract carvings she made in Yorkshire, via her colourful stringed sculptures, to her monumental later works in bronze and stone. There will be rarely-seen drawings, paintings and fabric designs, as well as photographs and other archival materials that illuminate the artist’s personal life and wide-ranging passions.

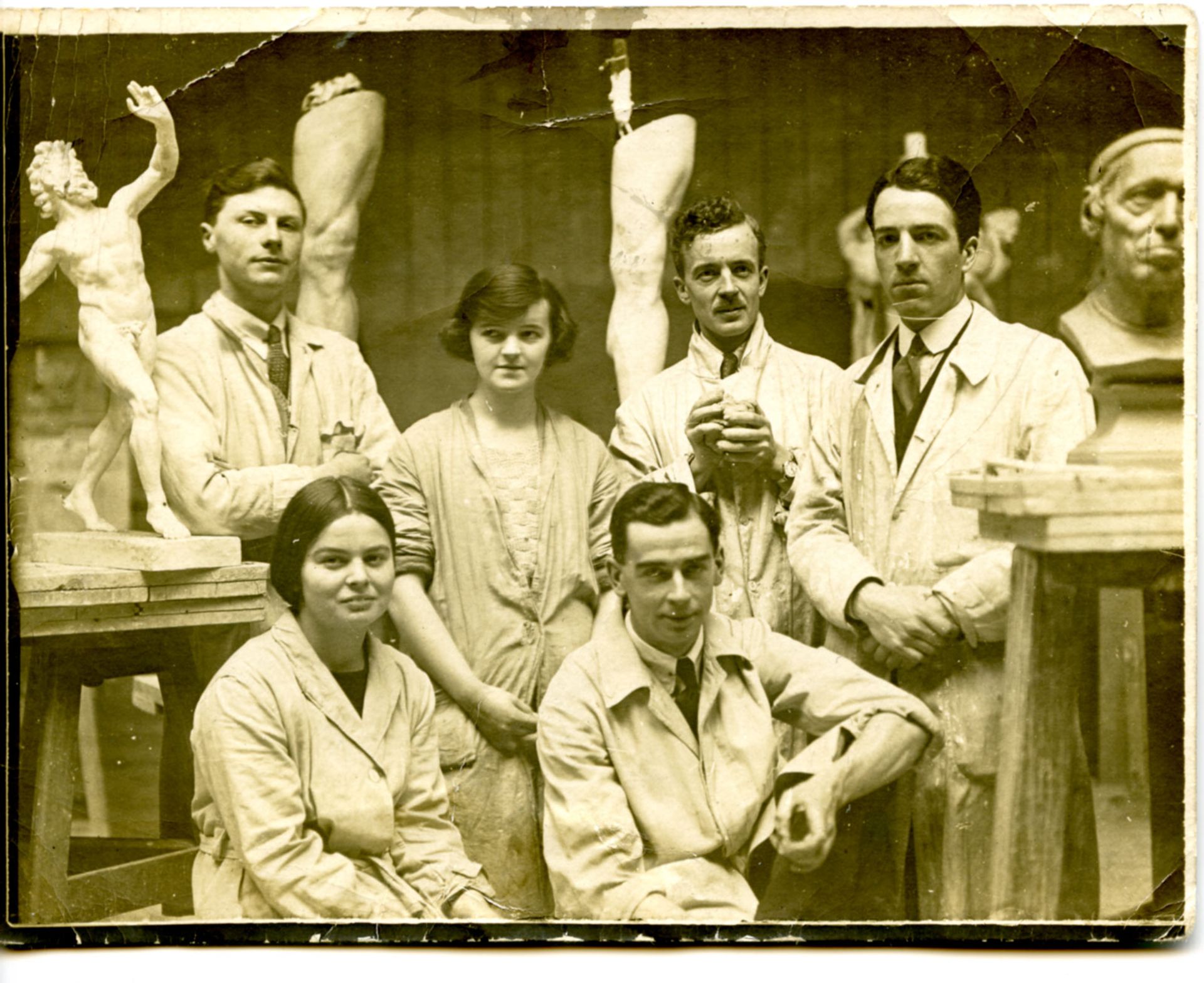

Barbara Hepworth (centre) with fellow students at the Royal College of Art in London (around 1921–23) after getting a Yorkshire Senior County Art Scholarship The Hepworth Photograph Collection © Bowness, Hepworth Estate

“Hepworth had a lot of seemingly unrelated interests,” says Clayton, who has also written a new biography of the artist, published by Thames & Hudson this month. “She was interested in spirituality and also in the physical world; she was interested in ancient ritual and also in space exploration. She saw these things as being connected, in the same way that she saw the world and every person in it as being connected.”

Since Hepworth wrote extensively about how her work should be presented and what she hoped visitors would glean from it, Clayton has been able to follow her guidance when it comes to making sense of it all. “It’s been like working with a living artist.”

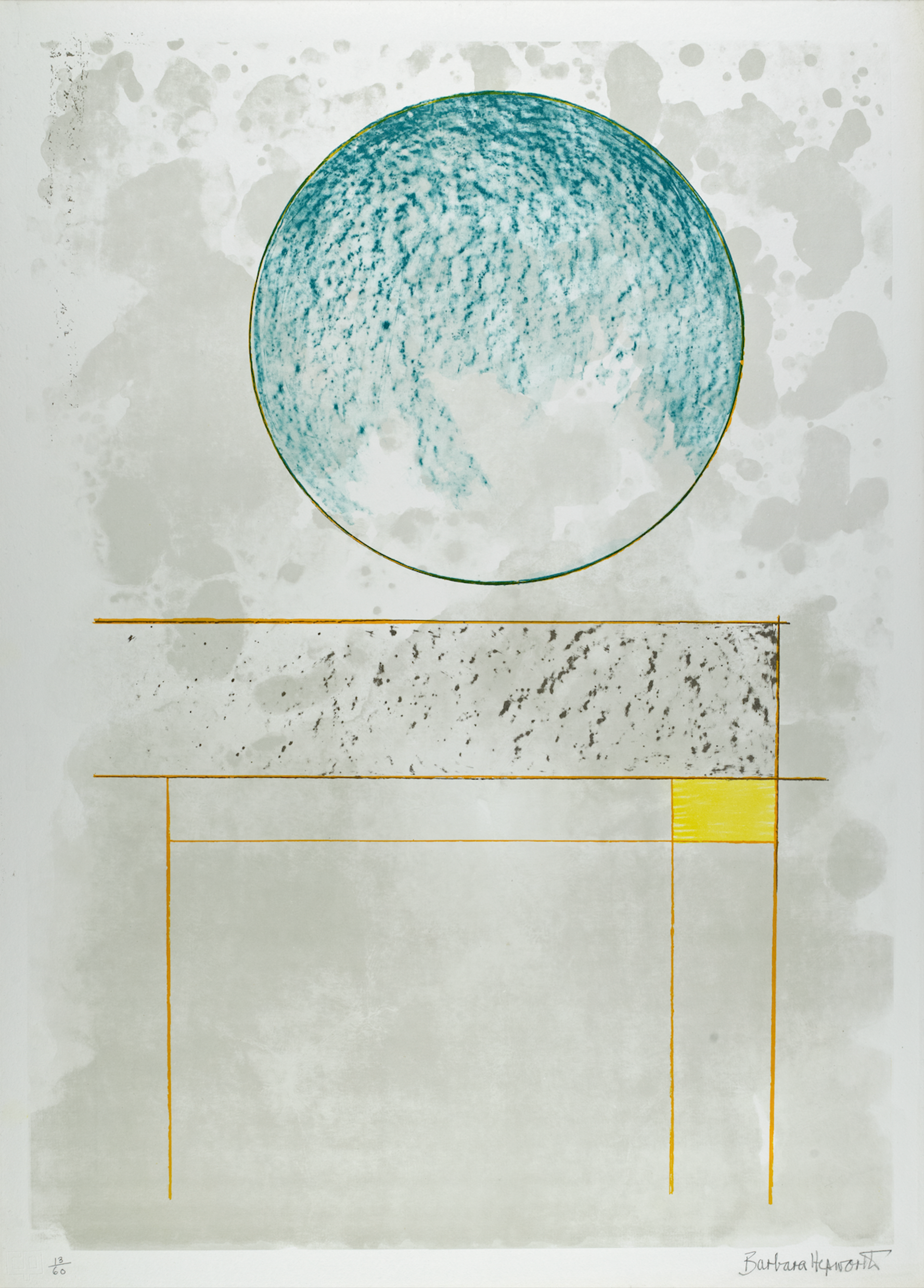

Hepworth's Sun Setting, The Aegean Suite (1971) Wakefield Permanent Art Collection © Bowness, Hepworth Estate

In fact, three living artists’ work will appear in dialogue with Hepworth’s. Veronica Ryan, who took part in the first residency in Hepworth’s former studio in St Ives, Cornwall, has been invited to make an intervention in the gallery’s permanent display of plaster, aluminium and wood prototypes. Tacita Dean is creating an installation that picks up on Hepworth’s preoccupation with how sculpture is represented in different forms. And a selection of works from the 1960s by Bridget Riley will be shown alongside Hepworth’s pieces from the same period.

Hepworth's Two Forms with White (Greek) (1963) Wakefield Permanent Art Collection © Bowness, Hepworth Estate. Photo: Jonty Wilde

“What I really wanted to do was tell the whole story of Hepworth,” says Clayton, referring to her many selves. Hepworth was a politically engaged individual who campaigned for nuclear disarmament and against the Vietnam war; a woman and a mother of four; and the first trustee of Tate who had a hand in acquisitions and therefore key developments in contemporary art collecting. The key to stitching these various strands together is of course Hepworth’s art, created over half a century.

• Barbara Hepworth: Art and Life, Hepworth Wakefield, Wakefield, 21 May-27 February 2022

• For a Barbara Hepworth reading list, see An expert’s guide to Barbara Hepworth: five must-read books on the British sculptor