The story of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (TMoCA) has been irresistible to journalists for four decades, laden as it is with period glamour, political intrigue and eye-catching art. To briefly recap: in the mid-1970s, the third wife of the Shah of Iran, Shahbanu Farah Pahlavi, was patron of a crash museum-building programme.

Surging oil prices had made Iran’s ruling classes rich, and Western economies, and therefore the art market, weak. In October 1977, TMoCA opened for Pahlavi’s birthday with a hastily but deftly assembled collection of Modern masterpieces from Gauguin to Giacometti, Picasso to Pollock. But scarcely a year after its glamorous opening, the Iranian Revolution toppled the Pahlavi dynasty. The museum and its collection went into deep storage—but remarkably survived almost intact.

“Have you heard there’s this American girl who’s going to start a new museum in Tehran?” That was the question circulating in New York gallery circles in 1974, when a young assistant curator in the department of prints and illustrated books at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Donna Stein, was tapped to work for Her Imperial Majesty’s Private Secretariat.

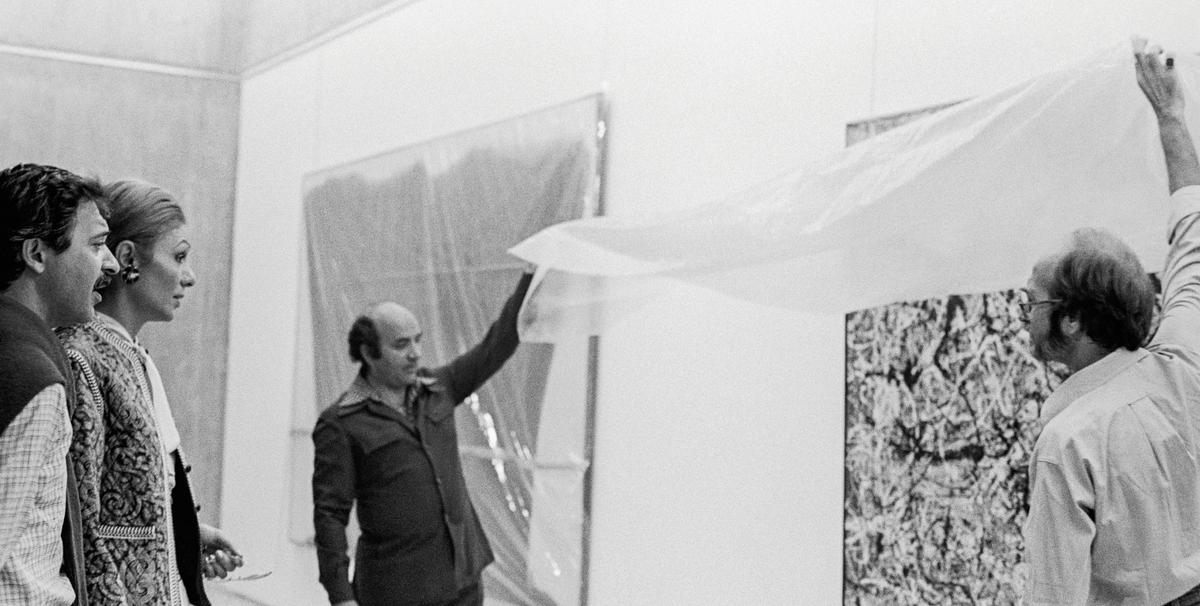

Farah Pahlavi (left) and Donna Stein, October 1977 Photo: Jila Dejam

Have you heard there’s this American girl who’s going to start a new museum in Tehran?

More than four decades later, Stein has written a memoir of those days, The Empress and I, staking her claim to have laid the groundwork for TMoCA’s famous collection. Success has many fathers, or mothers, but Stein clearly played a major behind-the-scenes role in putting the Western part of the museum’s collection together, and curated two of its opening exhibitions.

Stein writes that she first visited Iran in 1973, after working for six years on the curatorial staff at MoMA, on a fellowship to study the cultural impact of world’s fairs. A connection with Fereshteh Daftari, a member of one of Iran’s elite families who had interned at MoMA, opened doors.

Donna Stein at Persepolis in front of Northern Stairway in 1973

A letter came from Tehran, dangling a possible job. “I literally jumped for joy, bobbing up and down in my high heels,” Stein writes. Responsibilities were to include “purchasing prints that would represent the various movements and tendencies up to the present day”, running and organising catalogues and exhibitions, and “training Iranians to run the department after your departure”.

Stein flew to Tehran to interview for a post with the royal regime with her “eyes wide shut”—but asked for, and got, a $25,000 salary. On a site visit to the new museum, whose design mixed Solomon R. Guggenheim-style circular walkways with traditional Iranian wind towers, she was not afraid to point out “various flaws” to the architect and cousin of the queen, Kamran Diba. They included poured concrete walls that would make it hard to hang art for changing exhibitions, cramped staff offices and only one washroom. She was also unimpressed by early purchases of lithographs by Pablo Picasso that showed images of “women who looked like the Empress” but were not the best examples of his printmaking.

Back in New York, Stein’s responsibilities grew to include writing reports on works offered for sale to the Iranians. She recommended works by Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian, while warning her bosses not to settle for second-rate material and to inspect prospective purchases “in the flesh”. She would be particularly pleased by the Alberto Giacometti works purchased from Galerie Maeght. At the same time, “I got to go shopping for great art books—with cost as no object”.

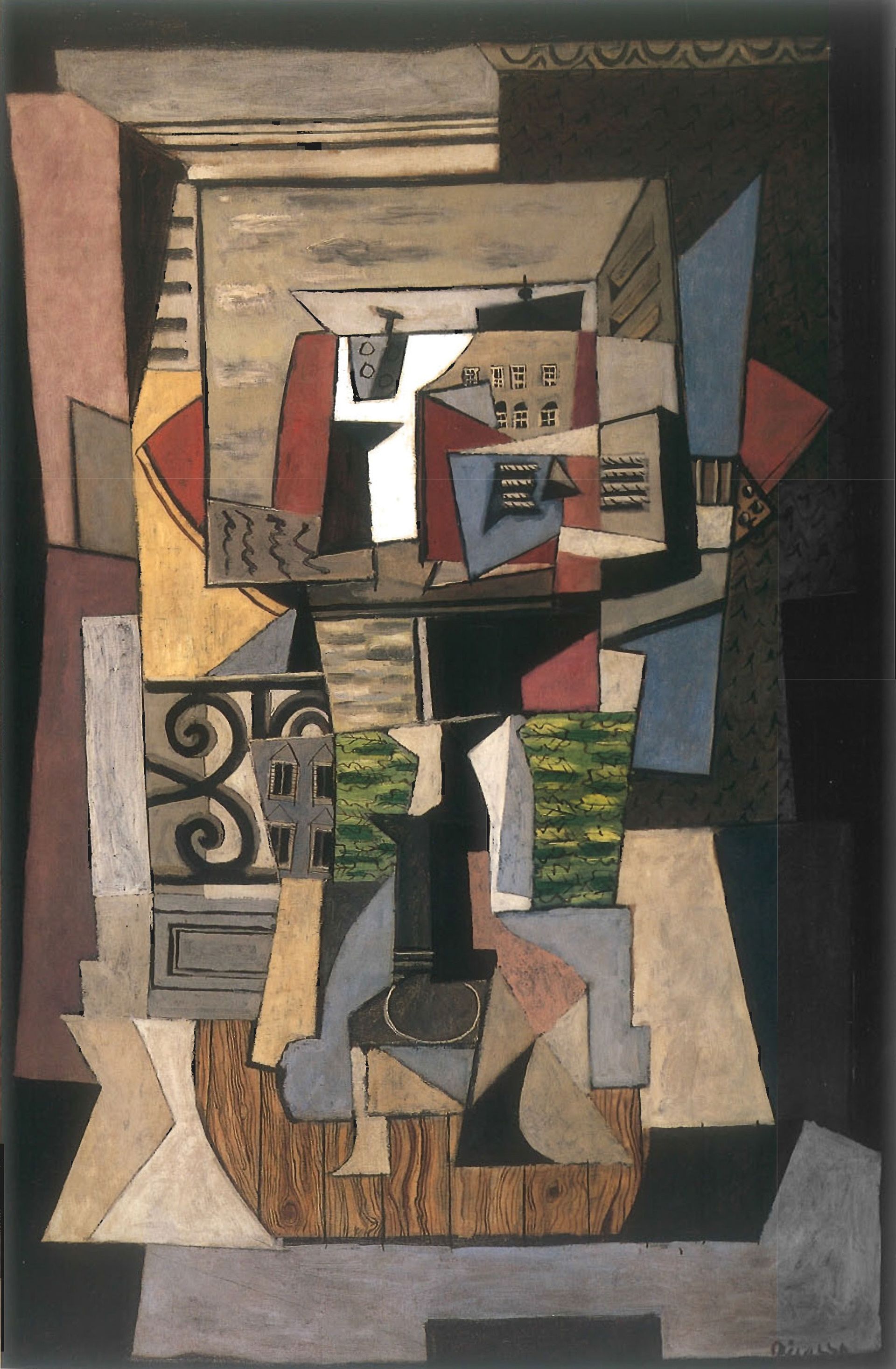

In May 1975, a group of influential Iranians showed up in New York to examine potential acquisitions. A two-week buying spree of 125 works included Jackson Pollock’s Mural on Indian Red Ground (1950), regarded as TMoCA’s signature work, and Picasso’s Open Window on the Rue de Penthièvre in Paris (1920).

Paul Gauguin, Still Life with Japanese Woodcut (1889), oil on canvas

Stein continues the story, in bracing style, with her move to Tehran. It was here that she “discovered what it was like to be a feminist in an all-encompassing Islamic cultural environment”: her boss had already propositioned her and she was referred to as “the woman who lives alone” by the staff of her apartment block. As dealers and collectors made their way to Tehran, the works of art continued to roll in: Toulouse-Lautrec, Marcel Duchamp, Paul Gauguin, Mark Rothko. Bribes and baksheesh were part of the trade, though Stein names no names.

Stein wrote the book now, she says, in part to assert a “leadership role” for a foreigner in the making of the Iranian national collection that has never been acknowledged. With a long career as a curator that ended as a deputy director of the Wende Museum of the Cold War in California, she says she never had time to write it before. Although she had written the first outline in 1977, it was only recently that she “could sit down and concentrate on the material, and actually produce what I wanted,” she tells The Art Newspaper. She drew on archive materials that run from correspondence with dealers and auction houses, to some 150 diary-style letters home. The result is undoubtedly a page-turner.

Pablo Picasso, Open Window on the Rue de Ponthièvre (1920), oil on canvas

The Tehran collection was kept in storage in revolutionary Iran until around 1999, when the first exhibitions of the work began, and there have been a succession of showings since. Only two works are known to have been damaged, one of which was an Andy Warhol portrait of Pahlavi. “It’s a very expansive collection considering how quickly it was put together between late ’74 and the middle of ’78,” Stein says. “It’s a really amazing array of very strong, very important work.”

“I had no idea at the time that there would be a revolution against [the Pahlavi dynasty] and that the museum collecting would stop at that time,” Stein says. “No one did. I was thinking in the long term, what was the potential for building a collection and how would you do that.”

• The Empress and I: How an Ancient Empire Collected, Rejected and Rediscovered Modern Art, Donna Stein, Skira Editore, 208pp, $45 (pb)

• For a response from our readers, see Letters to the editor | Donna Stein’s book about the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art is ‘misleading’ and has ‘inaccuracies’