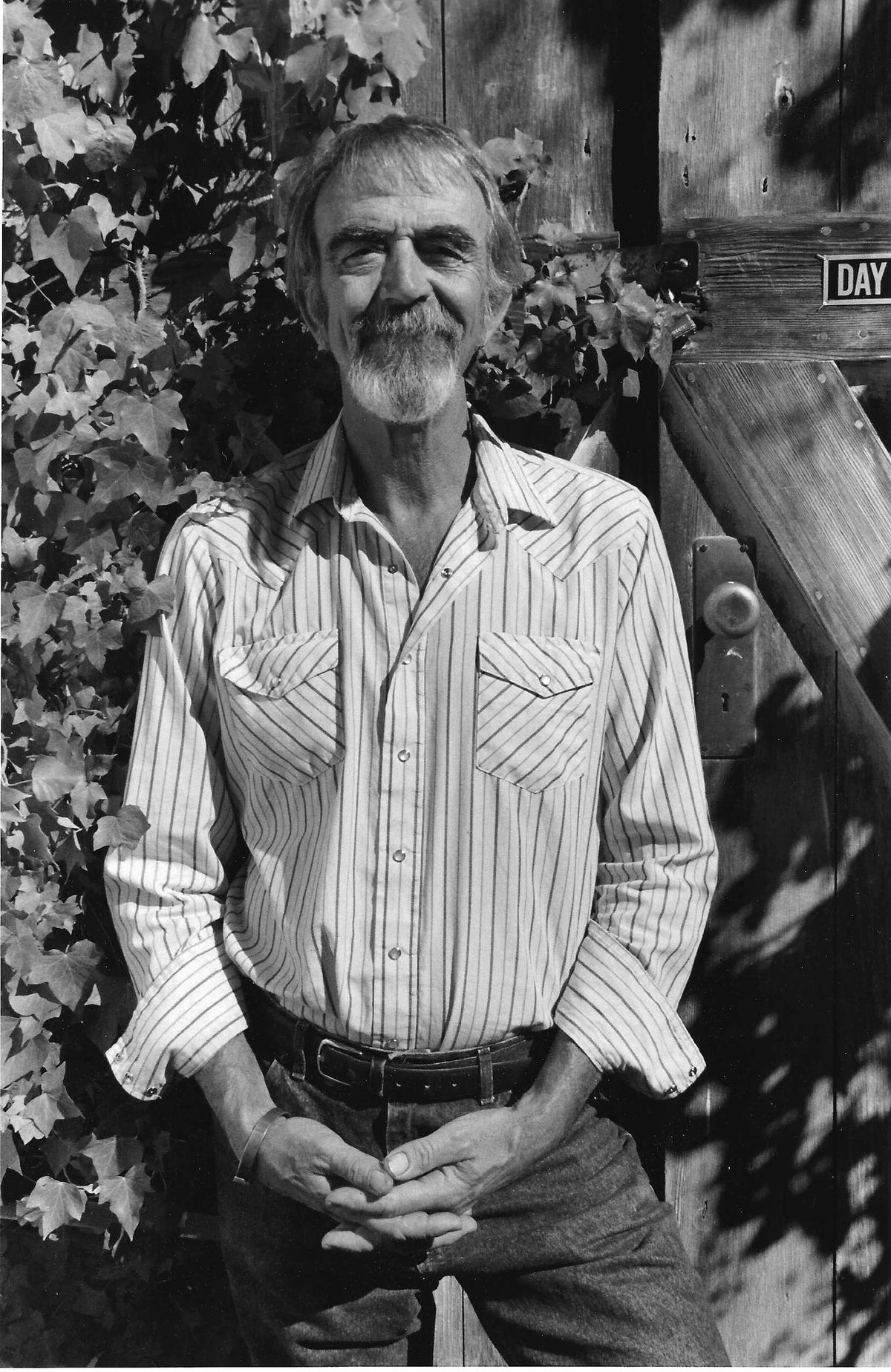

William T. Wiley, a beloved Bay Area artist and teacher and one of the founders of the Funk Art movement—which included Peter Saul, Robert Arneson, Ed Kienholz, Bruce Conner, Jim Nutt and others—has died, aged 83. His son Ethan Wiley confirmed to The San Francisco Chronicle that Wiley died from complications related to Parkinson’s disease, which the artist had lived with since 2014.

Wiley was born in Bedford, Indiana, in 1937. His father was a construction foreman who frequently moved the family around the country, and they ultimately settled in Washington State. In 1960 Wiley graduated from the California School of Fine Arts (now known as the San Francisco Art Institute), with a bachelor of fine arts degree and in 1962 earned his master of fine arts from the same institution.

The following year, he was hired to join the first group of art faculty members to teach at the University of California, Davis. There his colleagues included Wayne Thiebaud, Roy De Forest, Manuel Neri and Arneson. Although success as an artist came to him early—the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, which held a solo exhibition of his work just last year, first showed Wiley’s art in 1960 when he was 23—he threw himself wholeheartedly into teaching.

Wiley became a cherished fixture on the college campus, where he was known as a dedicated mentor to students. As a UC Davis graduate student, Bruce Nauman was among the young artists whom Wiley took under his wing, and the two would become close friends who frequently pushed each other to explore the outer limits of their creative capabilities. Wiley left UC Davis in the mid-1970s, and at that point was considered one of the most influential art teachers in the country. He would remain a resident of Northern California for the rest of his life.

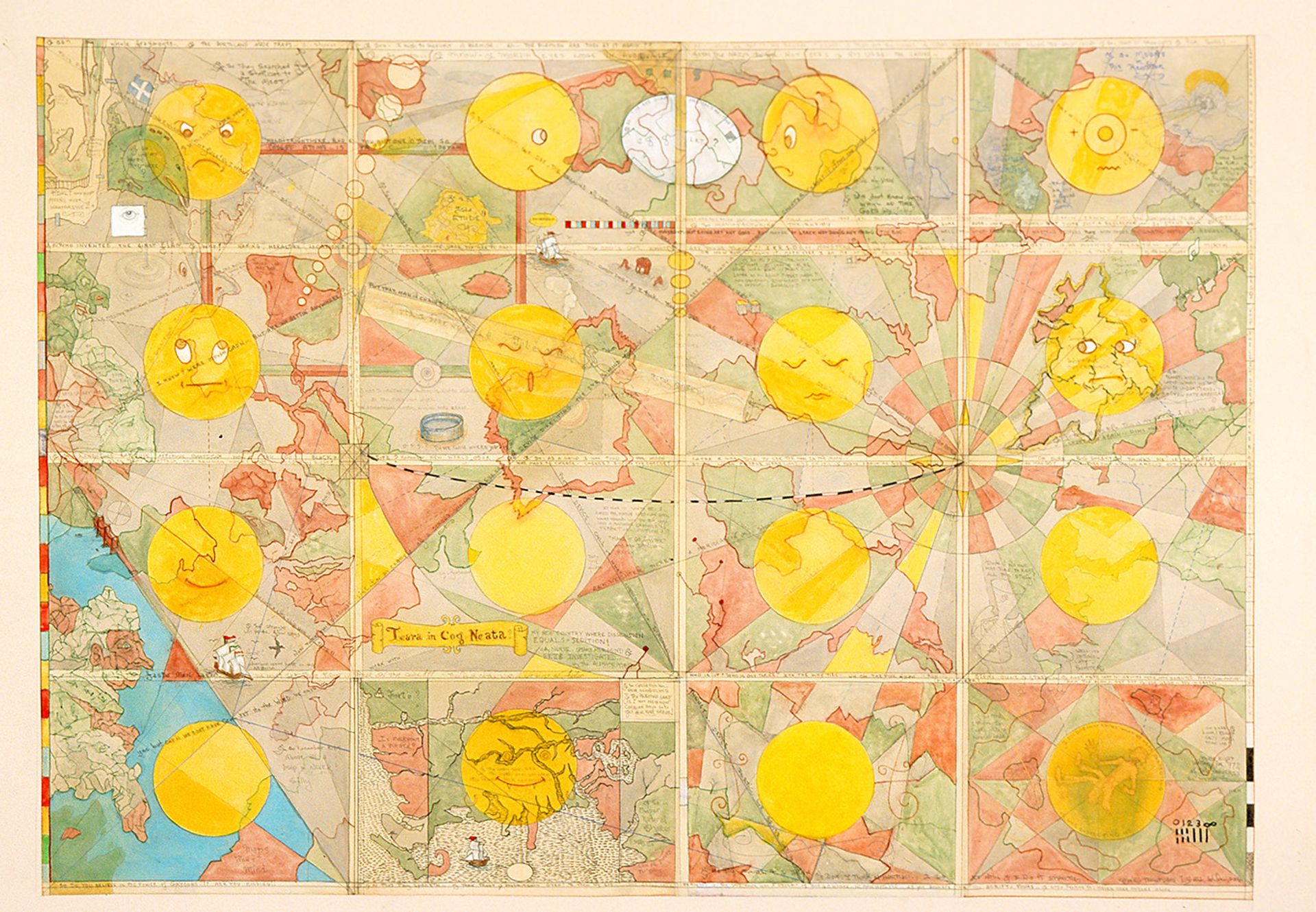

William T. Wiley's Meridian Moons Overwhatarewe, an acrylic on canvas, 2006 © William T. Wiley, courtesy of Parker Gallery and Hosfelt Gallery

“He was a wonderful spirit and I watched his work from the beginning when he was an Abstract Expressionist painter,” Thiebaud, who is now 100, told The Chronicle in a phone interview. “We disagreed all the time and still liked each other. He was a real gentleman and a lovely person.”

While still a professor, Wiley was a founding member of the Bay Area’s Funk Art movement, a collection of artists who steered away from Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism to create work with a figurative focus that often employed crass and political humour alongside wild, surrealist tendencies. It remained active through the 1960s and 1970s, and in 1967 the curator Peter Selz organised the defining exhibition Funk at the Berkeley Art Museum.

Though his early artistic recognition involved his sculptures, which often incorporated found objects and employed a Dada-ist humour, Wiley went on to be most widely celebrated for his watercolours and drawings. At a young age, he saw how Jasper Johns used art as a vessel through which to explore America as a concept and a reality in such works as Target with Four Faces, which Wiley encountered when it appeared on the cover of a 1948 issue of ARTnews. Wiley’s paintings strived to achieve a somewhat similar impact, melding his notions of Americana with his Funk Art sensibilities and interests in Zen Buddhism. The artist also incorporated performance and filmmaking into his work.

“Like his early influences Jasper Johns, Marcel Duchamp and [H.C.] Westermann, Wiley makes artworks that are dense with meaning and that are built by developing, recombining and cataloguing, in all media available to him, the elements of a visual vocabulary suffused with memory and emotion,” the curator Dan Nadel wrote in Artforum in 2019. “This activity is grounded in his Zen-influenced embrace of mystery and happenstance, combined with both a devotion to craft and an affinity for found, and especially natural, objects.”

William T. Wiley's Hidden Power No. 2, 1963 © William T. Wiley, courtesy of Parker Gallery and Hosfelt Gallery

“It is hard to overstate the influence of William T. Wiley,” says gallerist Sam Parker, whose Parker Gallery in Los Angeles co-represents Wiley with Hosfelt Gallery in San Francisco. “His ethos seemed to permeate his students, fellow faculty, really anyone he came into contact with. Both in art and life, he proposed provocative enigmas, riddles that are both humorous and profoundly meaningful. I will remember everything he didn’t say, the pregnant silence that allows you do to the thinking.”

Hosfelt Gallery singled out the text and wordplay that often accompanied the works that the artist made. “From stream-of-consciousness rambles to pointed critiques, he used humour, puns, sarcasm and double entendres to address the most consequential issues of our time,” it said in a statement.

William T. Wiley's Reading the Stains (1970) © William T. Wiley, courtesy of Parker Gallery and Hosfelt Gallery

Wiley had a prolific career that included the exhibition of his works at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, DC, as well as the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and many other institutions across the country and abroad. An exhibition of his work at UC Davis is currently being organised by Nadel for the Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Museum of Art at the university.