Visitors to an exhibition opening next month at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) will meet the intimidating warriors that greeted visitors more than 2,500 years ago when they arrived at the gigantic Palace of Darius at Susa in Iran.

Those long-ago visitors would have been confronted not just by the king’s elite guard ranked across the huge central courtyard, but by flanking rows of life-sized figures, heavily armed and elaborately costumed, marching along the walls in polychrome glazed brick friezes. Visitors to the V&A exhibition, Epic Iran, will see full-scale plaster casts of the frieze panels, made at considerable expense more than a century ago, newly restored—and, surprisingly, the curators believe—exhibited for the first time.

The originals of the grim but rather daintily coloured marching men survive in the Musée du Louvre in Paris. There may have been some chagrin in London over this: Susa was first excavated in the mid-19th century by the English geologist and explorer William Loftus, but he had moved on to other sites before more exciting discoveries were made by the French archaeologist Marcel Dieulafoy. The frieze panels were shipped back as crates of bricks and reconstructed in Paris, and soon afterwards the V&A commissioned the eight casts. The V&A had been collecting Iranian art since its founding but also regarded casts of antiquities as invaluable educational tools.

“We know they had arrived in London by 1891, but we have no record of them being exhibited,” says Melanie Vandenbrouck, curator of sculpture at the V&A. “It may simply be that the galleries were full and there was no room for such large objects. It could be that they were displayed at some point not in our records, but they certainly haven’t been seen in a lifetime.”

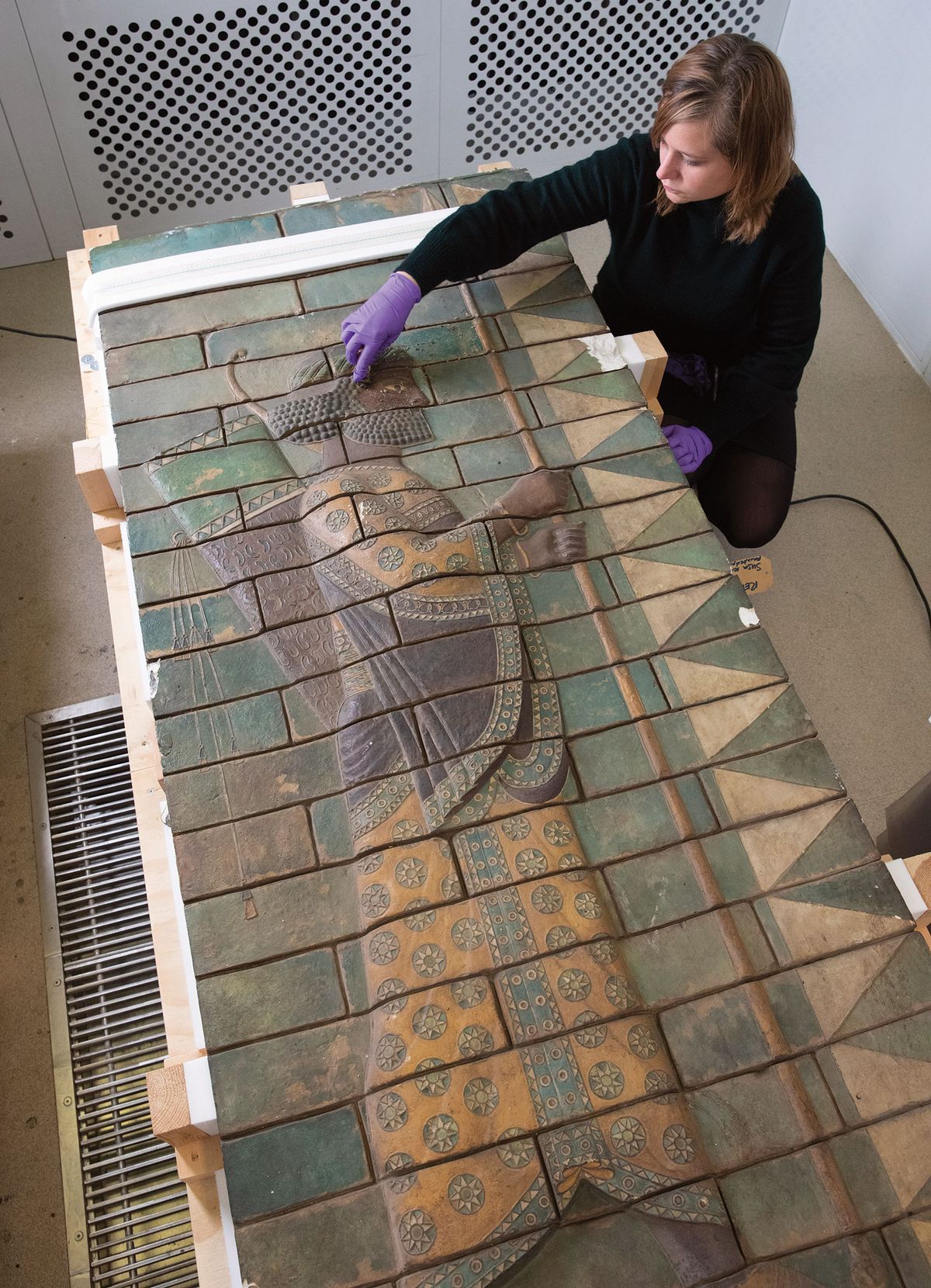

The conservation on the eight V&A casts involved gently cleaning the grime of more than a century, touching in paint chips and reinforcing the wooden skeleton that supports the fragile plaster © Victoria and Albert Museum

The quality is superb, says Mariam Sonntag, the conservator who has been gently cleaning the grime of more than a century and touching in paint chips suffered in many moves between stores. They have needed delicate handling. Each is the size of a large door and heavy; from the front they look solid and sturdy but the back reveals the fragile shell of plaster supported by a wooden skeleton that she has had to reinforce in places.

Visitors will be able to judge their quality beside one of the original panels coming from the Louvre, among many international loans to an exhibition celebrating 5,000 years of culture, art and history, the most comprehensive on Iran organised in the UK in almost a century.

John Curtis, head of the Iran Heritage Foundation, former keeper of the Middle East Department at the British Museum and curator of the V&A show, says that a consciousness of this rich and ancient history remains palpable in Iran to this day. However, little remains of the Palace of Darius, which once covered 250 acres but has been eroded over centuries and damaged by 20th-century development and conflict. “Mud brick crumbles very quickly when exposed, and now you’d hardly even recognise it as a hillock in the landscape,” Curtis says.

Remarkably, the record survives of exactly who commissioned and built the friezes. Darius the Great, Persian king of the vast Achaemenid Empire, left a vainglorious inscription about his “very excellent” palace, recording the woodworkers and stone carvers, the goldsmiths and brick makers. “The men who wrought the baked brick, those were Babylonians. The men who adorned the wall, those were Medes and Egyptians.”

Vandenbrouck hopes to save the panels from vanishing back into a dark store when the exhibition ends in September. “It’s tricky, space is always a problem here—but I’m working on it.”

• Epic Iran, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 29 May-12 September

UPDATE: This article was updated from an earlier print version, published in January 2021.