With fragrant, flowering walkways, the Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens was designed for leisurely strolls. But these days, paths near the American art galleries lead to a small junkyard: a broken fan, some old carpeting, a chest missing its drawers and other discarded objects spread out on the ground. It looks like the makings of a homeless encampment. And it is almost, but not quite, a work of art in the Hammer Museum’s new biennial, Made in LA 2020: A Version, which this year takes place at the Huntington as well as the Hammer.

The artist Ser Serpas is known for scavenging found objects near her exhibition site and transforming them into sculptural arrangements. But she currently lives in Geneva and could not make it back to Los Angeles during the pandemic to create a piece for the show. And her artist’s statement warns us not to take these discarded objects, gathered by a friend, as “a work or works”. She adds: “They were not collected or laid out by the artist; they were not collected or laid out on direct instruction from the artist. Rather, these objects constitute the potential for a work or works, a performance set at an indefinite time.”

Do the works, made before George Floyd’s death and before the American body count from Covid reached a staggering 500,000, already seem stale?

Or, flipping it around, you could see this small junkyard as a creative graveyard of sorts—a nod to all the works, performances, plans and dreams cut short by the spread of Covid-19. It also points to the challenges of staging a biennial during a pandemic.

Organised by independent curators Myriam Ben Salah and Lauren Mackler and the Hammer’s Ikechukwu Onyewuenyi, the show had a June 2020 opening date, until California museums shut down that March under Governor Gavin Newsom’s Covid orders. Over the summer the curators installed the show anyway—placing work by each of the 30 artists in both venues—in the hopes that the city’s museums would soon reopen. Many in San Francisco did, but virus transmission rates in Los Angeles County did not drop sufficiently. While commercial art galleries here could reopen, museums were not allowed to do so until late March.

Installation view of Diane Severin Nguyen's luminous photographs Photo: Joshua White

Given the biennial’s status since its start in 2012 as an of-the-moment cultural barometer, this nearly year-long postponement raises interesting questions. Do the works, made before George Floyd’s death and before the American body count from Covid reached a staggering 500,000, already seem stale? Do the themes emerging from the show seem somehow historic or nostalgic?

Certainly the pandemic did reshape the biennial, most dramatically in the case of Nicola L., the Paris-born, Los Angeles-based artist who died in late 2018. Her estate’s contribution to the Hammer, a recreation of La Chambre en Fourrure from 1969, is a furry purple box that you could, in better days, walk in and around and experience even more intimately by thrusting your hands into fuzzy sleeves hanging from it and placing your face against some plastic mesh. But what would have seemed playful and inviting just two years ago now seems life threatening, and the work on view is essentially a fossil. It makes you wonder about the future not just of interactive works but of hands-on museums everywhere, from children’s museums to science centres.

Nicola L., La Chambre en Fourrure (1969) Photo: © Joshua White

Undercurrent of anxiety

Still, most works in Made in LA 2020 remain vital and do manage to speak directly to the convulsions of our current moment in the not-so-United States, from the persistence of white-on-Black police brutality to the injustices of incarceration. Confronting Hammer visitors from the start is Harmony Holiday’s God’s Suicide (2020), exploring the five little-discussed suicide attempts by the celebrated author James Baldwin. The gallery also features recent paintings by Brandon Landers, whose portraiture combines some of the grotesque distortions of Robert Colescott with the everyday, picnic-type pleasures of Henry Taylor. His Wonders at the Hammer and Thursday at the Huntington (both 2020) are masterpieces of the everyday.

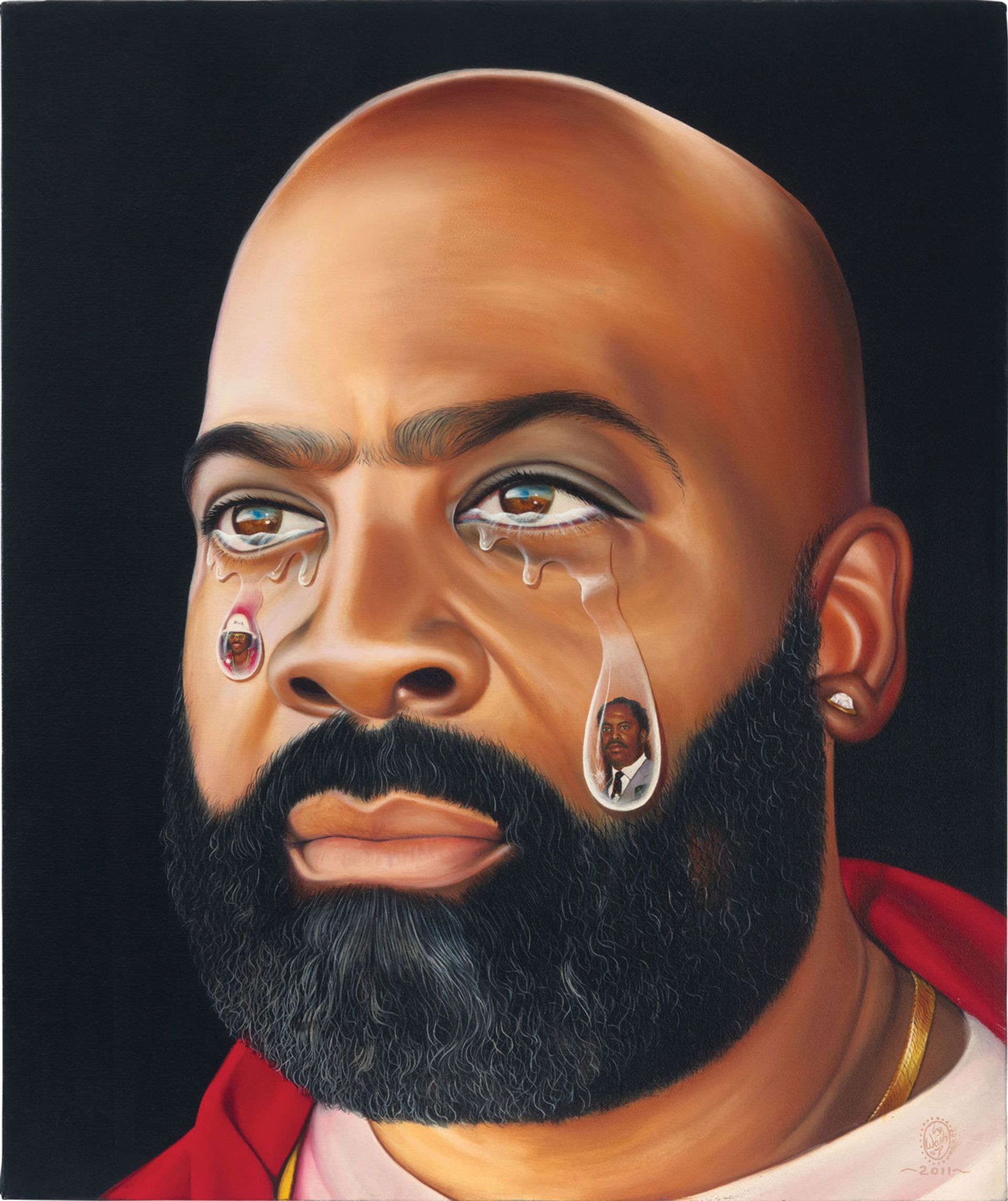

Fulton Leroy Washington (aka Mr Wash), Mr. Rene # MAN POWER (2011) Image: courtesy of the artist

Deeper into the show are portraits of celebrities and prisoners painted by former inmate Fulton Leroy Washington (aka Mr Wash), who was pardoned by President Obama after being sentenced to life for a drug offence in the 1990s, and Kahlil Joseph’s ongoing two-channel video BLKNWS (or Black news), which draws on an array of sources and appears in different versions at public sites around town. This gives the Hammer two powerful and inescapable soundtracks that play as you walk around: the BLKNWS audio (which spills out of an open gallery) and Holiday’s God’s Suicide audio (which unfortunately drowns out the audio of Aria Dean’s video installation nearby, showing a Black dancer trapped in a mirror-lined room).

Installation view of Kahlil Joseph's AliceTM (you don't have to think about it), 2016, at The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino Photo: © Joshua White / JWPictures.com

An undercurrent of bodily and social anxiety runs through several works in the show, mainly by women artists. Vietnamese-American artist Diane Severin Nguyen has taken close-up photographs of weirdly luminous and viscous plants or animals (or maybe inanimate objects?) in a vivid red-and-green palette—the colours of nature bleeding. They resemble some of Marilyn Minter’s photographs in their raw, wounded, oozing creepiness. Nearby is Jill Mulleady’s powerful triptych of MacArthur Park, Someone left the cake out in the rain (2020). The first painting shows an oversized black bird swooping over park denizens, a sinuous composition that recalls Toulouse-Lautrec views of the so-called demi-monde.

The Zurich-born Christina Forrer has made a masterful tapestry in cotton, wool, linen and silk dramatising the push and pull of family relationships called Gebunden II (2020), from the German word that can mean bound, tied or married. With flat, folk art-inspired figures, the tapestry depicts one person gleefully pressing his elbow on the head of another, who forces a sharp tongue in the ear of another, who seems to restrain another—one of the best images I have ever seen of how family members get into your head and under your skin.

Katja Seib, Mona Lisa's Smile (left, 2020); Bang bang (he shot me down) (right, 2020). Installation view, Hammer Museum Installation view, Made in L.A. 2020: a version, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. Photo: © Joshua White / JWPictures.com

The revelation of the show for me was the hallucinatory imagery of Düsseldorf-born painter Katja Seib. Her portrait of a pallid, yellow-haired woman sitting at a desk with blank paper and pen, while a drop of bright red blood falls from her fingertip as if she has been bitten by a snake from the jungle-themed wallpaper behind her, is enigmatic and unforgettable. In some canvases (she uses raw hessian), Seib identifies paint with blood. In others, she makes the connection between women making up their faces and her own work painting faces—lipstick being a rough slash of the artist’s brush. These hints of violence in the paintings read like anxiety made manifest, physical, visible.

Seib has large paintings at the Hammer and smaller canvases at the Huntington, which is fairly typical of how the show plays out across the two venues. But some artists put the Huntington’s permanent collection to interesting use, such as Buck Ellison situating one of his photographic portraits of New England, prep school-worthy white privilege alongside 18th-century American art and mahogany furniture.

Sabrina Tarasoff, Beyond Baroque: A Haunted House (2020) Courtesy of the artist, Zion Fenwick, and Twisted Experiential Design. Installation view, Made in L.A. 2020: a version, The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino. Photo: Joshua White / JWPictures.com

The biggest surprise at the Huntington is Beyond Baroque (2020) by Sabrina Tarasoff, a walk-through haunted house that integrates artwork by Tony Oursler, Marnie Weber, Mike Kelley, Bob Flanagan, Sheree Rose and more. Zombies pop out of darkness, a BDSM video plays near a display of whips and angry graffiti such as “Bitches Get Stitches!” covers the walls. The project, really an exhibition within an exhibition, is a throwback to the 1980s aesthetic of the abject.

But right now, given the pandemic, this over-the-top horror show feels too on the nose. These days, a miniscule drop of blood in a painting and a tapestry about extreme family proximity feel terrifying enough.

• Made in LA 2020: A Version, Hammer Museum and Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens, Los Angeles, until 1 August