The evocative Upper Paleolithic art (dating from roughly 44,000 to 12,000BC) found in caves in France and Spain has long intrigued art historical and scientific researchers. But one facet has stumped many scholars: Why are so many of these paintings found in remote, narrow, hard-to-reach halls or passages that cannot be navigated without artificial light?

A team of Israeli researchers suggests the answer: the torches used by the artists in such enclosed spaces triggered hypoxia, a state resulting from a reduced oxygen concentration that can stimulate dreams and hallucinations. By seeking out these tight spaces, the researchers suggest, the artists were aiming to achieve an altered state of consciousness that would put them in touch with the cosmos and inspire their imaginations.

Writing in the journal Time and Mind, an archaeological publication that explores consciousness and culture, the three researchers—Yafit Kedar, Gil Kedar and Ran Barkai—note that the natural oxygen concentration in the atmosphere is 21%. Using a fire dynamics simulator developed by the US National Institute of Standards and Technology, the researchers projected the potential oxygen concentrations in a variety of enclosed spaces with notably decreased air flow when torches were used.

Fire generated by torches in tight spaces creates a hot plume that reaches the ceiling, creating two gas streams that flow in opposite directions along the ceiling and near the floor, they write. The lower layer flows inside the cave and creates the higher oxygen concentration while the upper layer heads toward the cave’s mouth.

Buttressing the findings of earlier researchers, they found that oxygen levels in narrow passages or in halls with a single passage declined in a short time to below 18%, which is known to induce hypoxia in humans. Affecting nervous tissues including those in the frontal cortex and the right hemisphere of the brain, the researchers note, people experience an increase in dopamine associated with dreams and hallucinations, such as the sensation of flying or floating.

That oxygen level contrasts with higher concentrations of oxygen in larger chambers near a cave’s above-ground opening, where humans carried out most of their daily activities, they note. Art can be found there as well, and out-of-body experiences in such places cannot be discounted, they say. But they were most curious about the hard-to-reach spaces.

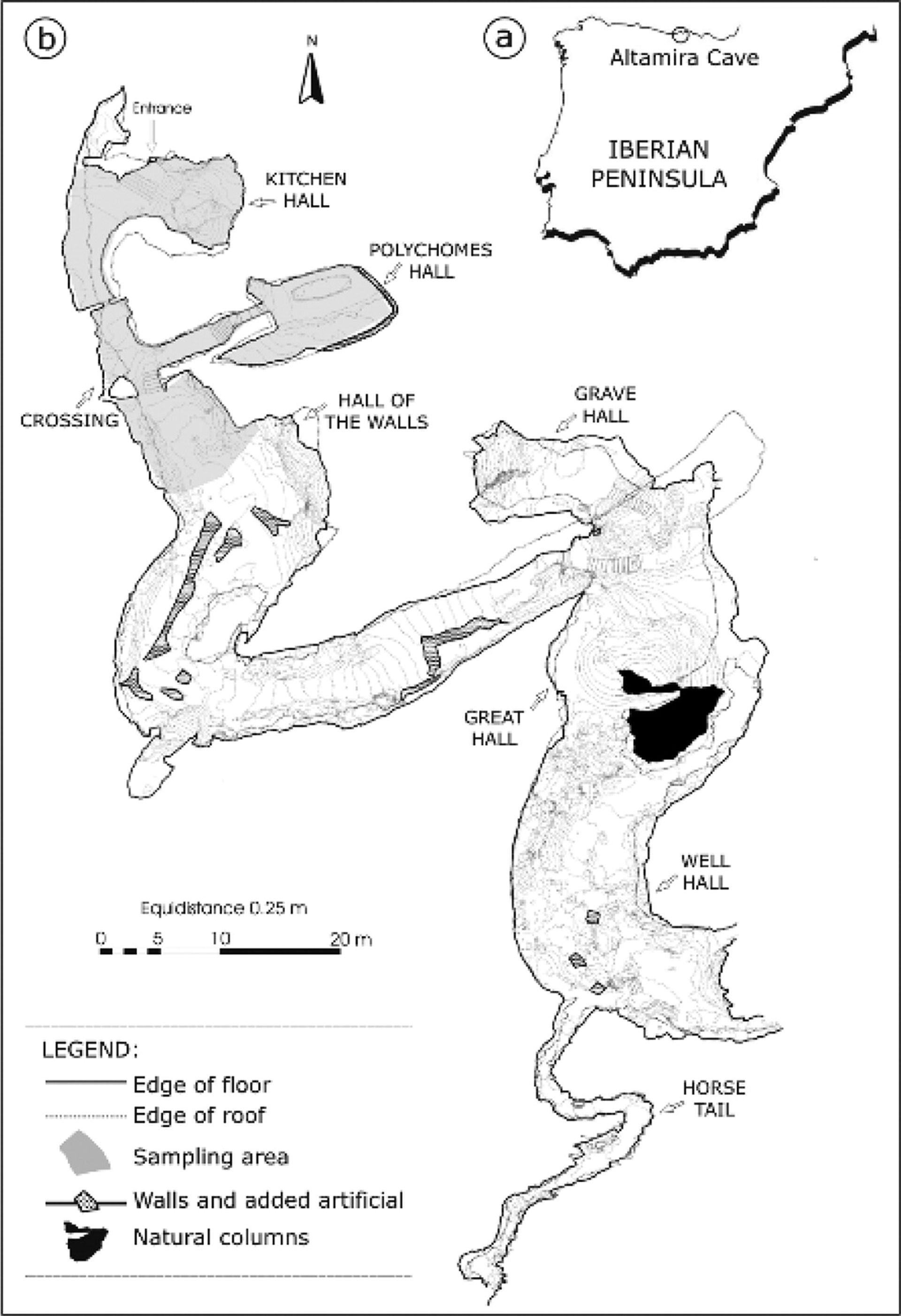

Surveying conditions at various cave sites from Rouffignac in France’s Dordogne region to Altamira in Cantabria in northern Spain, the researchers noted that some of the prehistoric art is located as far into the cave as people could go, by crawling through very narrow passages, climbing steps, crossing treacherous ledges and descending through shafts. The images range from paintings to engravings, often of animals such as bison, mammoths or rhinos, as well as stencils of hands.

In the Altamira cave in northern Spain, art has been found in the the narrow Horse Tail passage. Courtesy of Prof. Saiz-Jimenes

“When interpreting the use of deep caves in the Upper Paleolithic period, we should consider how those early humans may have conceived subterranean hollows in the ground or inside mountains as part of their world cosmology,” the researchers add, citing anthropological studies.

“We contend that entering these deep, dark caves was a conscious choice, motivated by an understanding of the transformative nature of an underground, oxygen-depleted space.”

The anthropological and cultural implications are tantalising. Some researchers have suggested that the images in prehistoric European cave art are related to shamans, who enter a trance-like state to interact with a spiritual world for healing, hunting and other purposes, they write.

But “entering ASC [an altered state of consciousness] is within the capabilities of humans in general,” they add, “and thus it is probable that not only specific individuals were involved in penetrating and [creating art in] dark and deep caves.”