Alice Channer once said, “The 21st century needs objects that are vulnerable, uncertain, other, alien.” This aptly describes the British artist’s sculptural works, which subject a wide range of materials, both organic and man-made, to a range of industrial and post-industrial processes to form hybrid relationships. Channer is interested in making their multifarious means of production visible as part of the works, to explore ideas around the interaction of bodies, processes and timeframes—from primordial geological rock formations to high-speed digital copying and mass-produced fashion.

Channer’s solo exhibition of new works, in materials ranging from machined Portland stone and folded snakeskin leggings, to cast aluminium and pleated silk satin, opens at Large Glass in London on 22 April (until 26 June). She is also showing at the Liverpool Biennial (until 6 June) and in Breaking the Mould: Sculpture by Women since 1945, an Arts Council touring exhibition opening on 29 May at Longside Gallery at Yorkshire Sculpture Park. This summer Channer is showing a public work as part of Sculpture in the City, in the City of London, and her permanent sculpture commissioned for the Engineering Department Building of the University of the West of England in Bristol is unveiled in June. In 2022 she is participating in High Desert Test Sites in Joshua Tree, CA, curated by the Whitechapel Gallery’s Iwona Blazwick.

The Art Newspaper: You’ve described your work as “a 21st-century process art”. Can you explain what this means?

Alice Channer: When we think about process art, we think about a human body making gestures. But in my work, the bodies are multiple, and they’re not necessarily human. So the bodies that are authoring the processes could be the bodies of machines, or the bodies of machine operators. They could be the bodies of bacteria, of plants or rocks in the ground beneath our feet. What I mean is that these processes are multiple and not authored by a singular body or identity of “the artist”. I use a lot of processes, but I’m always working with others. It’s not my job to be an expert; my job is to say: “This is what it feels like.” That’s where I find form.

You merge the organic, the chemical, the manufactured, the natural and the artificial. And you also make a point of highlighting the similarities between different processes, scales and timeframes—often in a single piece.

I think that’s very much a character of the world I live in. We are embedded in these materials and processes, and we cannot separate ourselves from them. This is definitely something we’ve become really aware of on a bodily level over the last year—the way in which tiny bodies can invade multiple human bodies on a planetary scale. So the way that different scales interact is something I experience every day—it’s right here. I’m working from a position of complexity and complication. All these materials also bring huge problems and I’m trying to work with those. I don’t have any answers, but I can at least be honest about what these materials and processes are, and try to make them visible and to do that within concentrated, elegant forms.

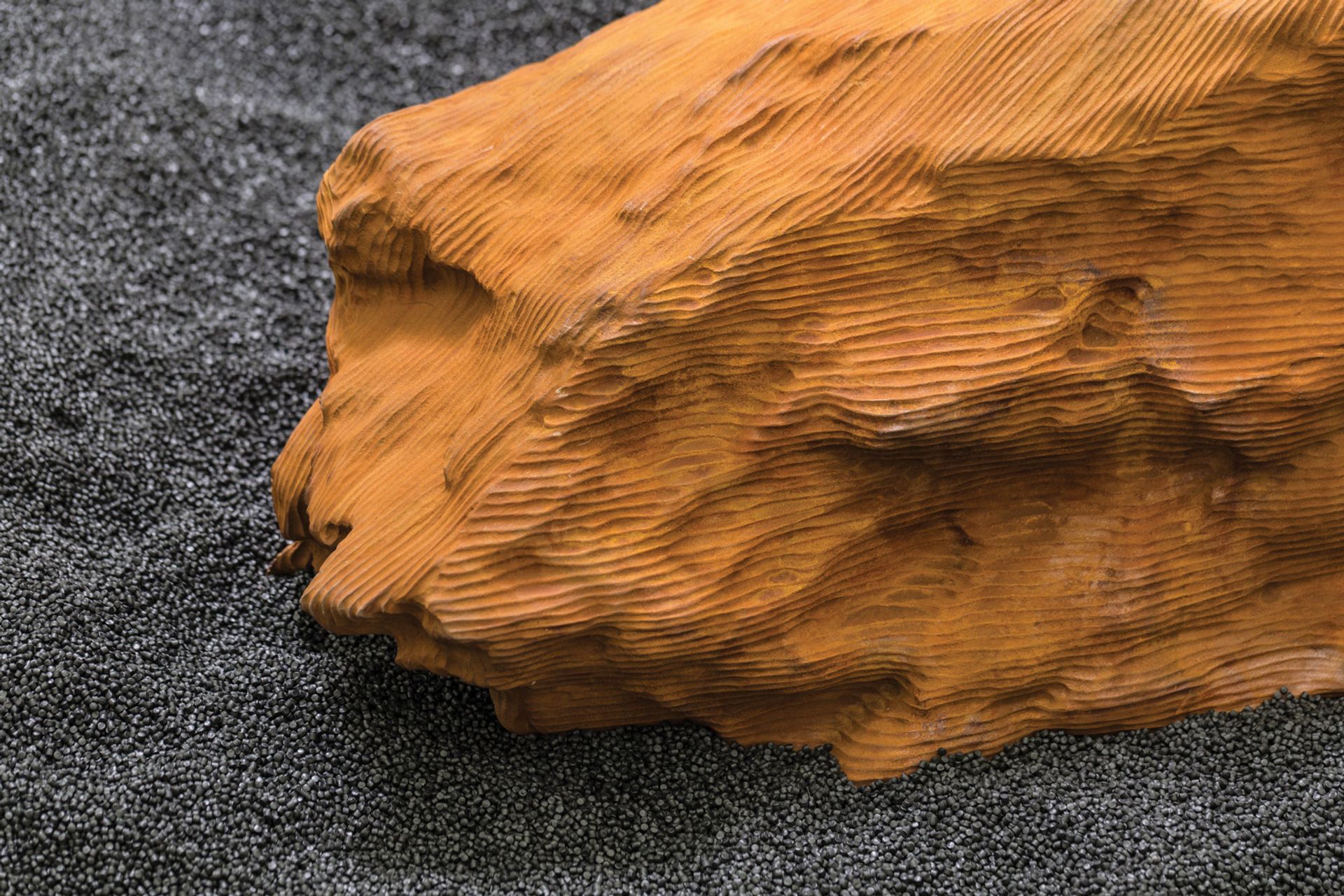

Alice Channer's Soft Sediment Deformation, Photosynthesising Body (H o r i z o n t a l Empress Wu) (2020) Courtesy the artist and Large Glass); Photo: Lucy Dawkins

Your printed, pleated crepe de chine work, Soft Sediment Deformation, Four Bodies (Ley Lines) 2020, for the Liverpool Biennial fuses the geological folding of rock, the digital stretching and distorting of an image, and the mechanical pleating of fabric. At Large Glass a similarly created work in silk satin takes the leaf of a giant hosta plant as its starting point.

These different processes of expansion and compression are still visible and can be felt in the final works. In both cases the distortions, disruptions and mutations can be quite violent. They create this surface which is textured—it has glitches and ruptures and stretches all over it, a lot like my own skin. I think that’s an honest surface for an object to have.

Art does this; it can hold things in its surfaces that we can feel when we encounter it. The hostas were my lockdown works. My neighbour brought them out to the front of his house and they were like nothing I’d seen before—like these giant pleated leaves presented themselves to me.

It seems important that your sculptural surfaces, whether metallised crab shells or cast corten steel, always carry the various histories of their production.

Yes. All my work has textured surfaces, which I would describe as pleated, even if the surfaces are hard. And they’re pleated in the way that they’re folded, and they’re multiple. They’re not smooth and they’re not continent—they are surfaces that are ruptured and porous, in many ways.

I’m repulsed by the idea of sculpture that has a smooth and continent surface. Last summer, when the sculpture of Edward Colston was pulled down in Bristol, along with many statues in other places, they could be pulled down because they’re hollow. They’re not solid. Monumental casting is a lie, because these figures are made to look as if they’re solid, but they’re not—they’re really quite light. You can grab them by the ankles and pull them down quite easily.

Nonetheless, you have used a monumental scale for Megaflora, a new cast aluminium work at Large Glass, which blows up a bramble branch to more than three metres high but reveals a hollow centre.

I do want to make monumental sculpture, but on different terms. Showing with this casting that it’s hollow seemed to me the only way I could make it. It becomes like a tree that’s been struck by lightning, so you’re reminded of another form. And the cast is also extremely beautiful on the inside. There’s something arterial about the texture—it looks like the inside of a vein or a ventricle.

Channer’s new work Megaflora—a three-metres-high cast aluminium bramble—in production Photo: ©Noel Hochuli; Courtesy of the artist and Large Glass, London

Why a bramble?

Brambles really interest me. They are in all the industrial or ex-industrial areas where I live and work and are always all around me. They’re very resilient because of their thorns and their ability to grow in these compromised areas, but they are also vulnerable. They are soft and they bend. They are survivors.

I took a small 10cm section that was 3D-scanned and then stretched before being milled from foam using a CNC router—a robotic arm with a drill bit at the end. This is how all the huge things by Gormley, Kapoor and Urs Fischer are blown up—they take a scan from a model and then it’s blown up and milled from foam. But you don’t usually see this process on the surface, whereas I wanted the router marks to be left visible, like scars on a skin. The whole thing was then sand cast in aluminium in a single piece.

Sand casting is an ancient process, similar to how the first arrowheads were cast, but it’s also quite industrial: all the manhole covers I walk over every day have been produced by sand casting. But in this case, and also in another cast piece I’ve made for Liverpool, I use aluminium, which feels like a metal of the 21st century.

You seem to be both revealing and celebrating all the processes used to create the end product.

I don’t want to fetishise the means of production. I want to stress that there are multiple births and multiple origins to these works. It’s not that they have one singular authentic origin—they come from many places, as do all of us. We are formed, not once, not twice, not three times but millions of times every day.

There’s also a deliberate glamour: your materials can include lamé, opulent silks, dresses, snakeskin print leggings and blingy metal finishes.

I weaponise glamour. I use it strategically, to complicate the charged situations that I’m making and showing work in. I see clothes as a kind of armour that can change and mutate. I’m not very interested in all these conversations about deep time. My work is very much about the present.

Alice Channer's Burial (2016) Courtesy of the artist and Konrad Fischer Galerie; Photo: Henning Krause

This summer, as part of Sculpture in the City, you are unveiling Burial, a public work in the graveyard of St Botolph-without-Bishopsgate in the City of London which will remain in situ for a year.

It’s called Burial because I was thinking about these two rocks of Corten steel as a kind of mourning procession. Their rough dimensions are approximately the same as an average-ish stretched human body and their forms, which are also hollow, are similar to sarcophagi. What interests me about sarcophagi is that they can be seen as exoskeletons, hollow hard shells that are made to hold soft bodies whilst those bodies are in a changing state. So there's a relationship to the crab shells that I’ve used in other works. The rocks were cast from lumps of concrete I collected from demolition sites as evidence of the changes that were happening in the city around me. Being made from Corten steel, their forms look weirdly organic, even though they’ve been produced using the technological processes of scanning, stretching, milling and casting. I’m very excited to be showing in this graveyard, surrounded by glass and steel skyscrapers—it makes you very aware of different kinds of time, including that of the two rocks themselves, as the rust forms and changes on their surfaces.

How do you feel about installing a public work to be experienced at random outside the gallery?

People rightly take ownership of objects that are in public space, as we saw last summer. Artworks are like people, we all have layers and layers of identity, some of which we don't even know ourselves. Getting to know an artwork is like getting to know a person:

some of it reveals itself over time, some of it doesn’t. So I think it’s a really exciting moment to be thinking about public sculpture.

Biography

Born: 1977, Oxford

Lives: London

Education: 2006, BA, Fine Art, Goldsmith’s College, London; 2008' MA Sculpture, Royal College of Art, London

Key shows: 2015 Aspen Art Museum; 2013 Hepworth Wakefield and Frieze Sculpture Park; 2012 South London Gallery; 2010 Glasgow International; 2009 World Class Boxing, Miami

Represented by: Large Glass, London; Konrad Fischer Galerie, Berlin and Düsseldorf