Two text-based works by the artist Dread Scott, installed this week on the West 42nd Street façade of the Playwrights Horizons theatre, have already run up against the racist power structures they were made to critique. One is a 2007 piece titled Imagine a World Without America, in which the titular phrase is rendered over a map devoid of North America. The second is a new piece, with a simple white font on a black background, that reads: White people can’t be trusted with power. When Scott posted an image of the latter on social media, it was removed. “Instagram dubbed it ‘hate speech’,” the artist says. “Then I made a second post saying that they censored it, and they deleted that too. The justification of censorship for both was ‘hate speech’.”

About three hours later, the post had been returned to view on the platform. “When I protested the banning, Instagram said they reviewed the post and concluded that it was indeed hate speech, so a human made the decision to confirm their algorithm,” Scott says. “I think the only reason they changed their mind is that lots of people were starting to repost the work, and were asking questions about why I couldn’t.” Scott made a third Instagram post, which read: “White people’s algorithms can’t be trusted with power”, and this, too, was removed on the grounds of hate speech. The artist describes the whole episode around the project—meant to probe questions around who holds power, both nationally and globally, and how they choose to wield it—as “Kafkaesque”.

One aim of the installation, which is due to remain on view until 9 May, is to get viewers to envision more equitable ways that such power could be used towards a global good. “I want people to dream in a romantic sense about what kind of world we want,” Scott says of the piece Imagine a World Without America. “What would the world be without this country that has such a profound influence? Some people, including myself, view it as a profoundly negative impact, while others might view it as positive. Either way, if you take America out of the equation, you get a very, very different world.”

Dread Scott's Imagine a World Without America (2007) installed at the Playwrights Horizons theatre Photo: Marc J. Franklin

“It’s not a simple question, and it’s not about geography or removing everybody that lives within the US borders,” he adds, “but politically, philosophically, economically, socially—a world without everything that America is opens up tremendous possibilities for people to get to a world we’d actually want to live in. If people in this country would stop thinking like it’s rulers do, then humanity would have a much better shot of having a life fit for human beings.”

For more than 30 years now, Scott has been creating work that delves into America’s violent and racist history and present. In 1989, as an undergraduate at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Scott made a work titled What Is the Proper Way to Display a US Flag? It was a participatory installation that included photographs of South Korean students burning the American Flag as well as flag-draped coffins of US soldiers returning from the Vietnam War. Viewers were encouraged to write their answers to the title’s prompt in a notebook that was displayed with a flag laid on the ground in front of it, so that people could choose to stand on it. The work caused a wave of national attention few artists receive. Then-president George H.W. Bush told the Chicago Sun-Times that the work was “disgraceful”, and senator Bob Dole said: “Now, I don't know much about art, but I know desecration when I see it.” There were protests in front of the school, and Congress responded by unanimously passing a law making it illegal to deliberately display the American flag on the floor. In other words, they outlawed Scott’s work.

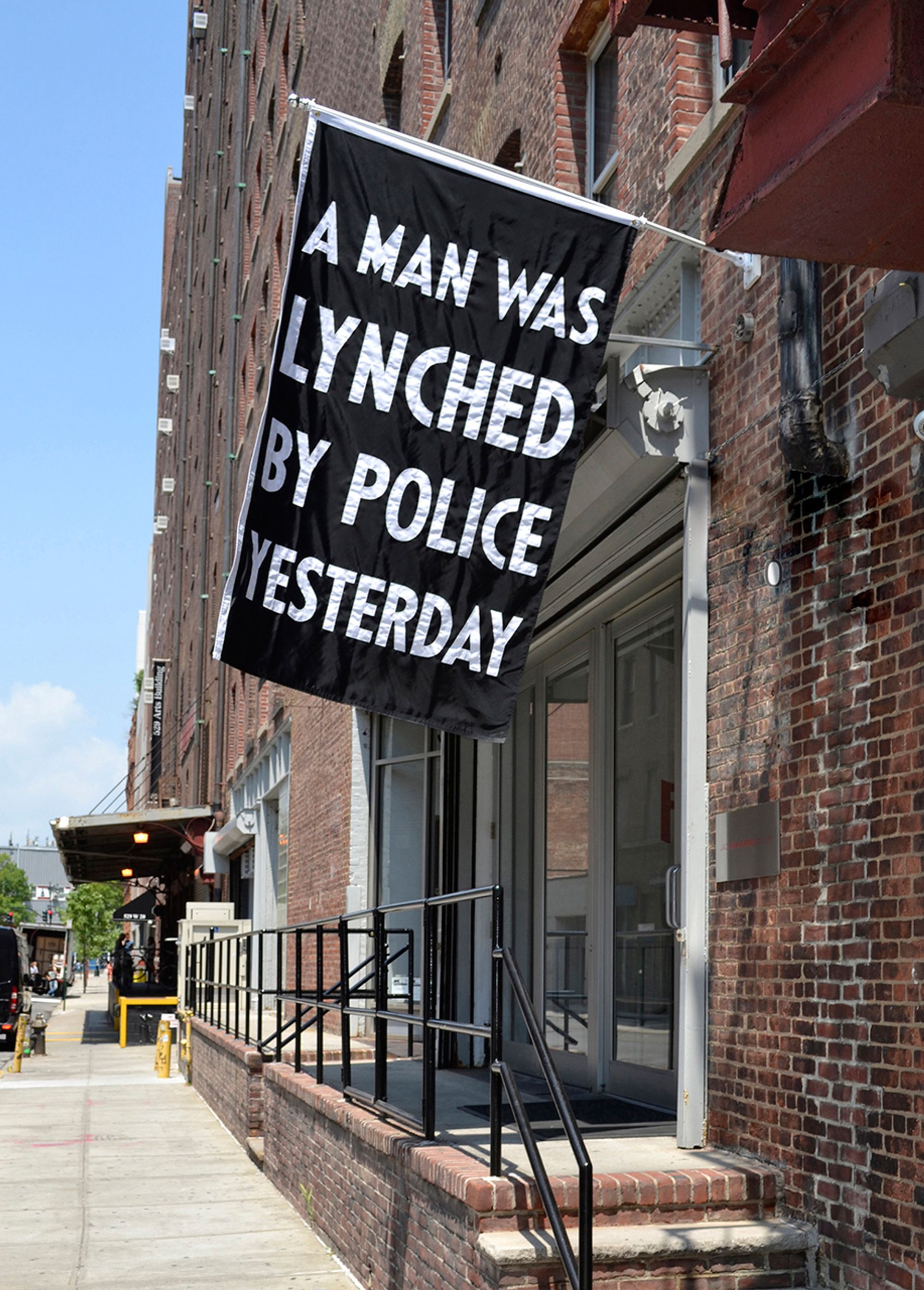

A Man Was Lynched By Police Yesterday (2015), by Dread Scott

In 2015, he created A Man Was Lynched by Police Yesterday—a black flag with white letters—inspired by a flag that the NAACP would raise outside of their New York headquarters in the 1920s and 30s when lynchings took place throughout the country. Scott’s piece was a response to the death of Walter Scott, who was shot in the back by a police officer in South Carolina after being pulled over for a faulty brake light.

“It was first shown in a small gallery in Des Moines, Iowa, and frankly, not too many people noticed it,” the artist says. The following year, in the wake of the police killings of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile—which occurred less than two days apart—the flag became a last minute addition to a group show at Jack Shainman in New York, where it flew outside the gallery. “People started connecting this art to the broader movement for social justice,” Scott says. The work has since become a mainstay in the fight for equity, and one that extends far beyond the art world. “Just yesterday I got an email from a pastor who wants to get a copy to display because his church is across the street from a police station,” Scott says. Vogue even used it to illustrate an op-ed by the Black Lives Matter co-founder and performance artist Patrice Cullors. “The work is relevant and being used, and that’s great,” Scott says, “but the point is, we need to get to a world where these horrors don't happen anymore.”

In recent years, as national protests against racism and violence against people of colour has forced a cultural reckoning, Scott’s work has garnered more support, including a Guggenheim Fellowship this year. “The art world is paying attention to me in a way that it hadn't for decades, and it’s because suddenly large sections of people are saying, ‘Oh, wait, the police are murdering Black people—who knew?’ I've been making work about this since the mid-1990s. I truly wish it was not so damn relevant.” he says. “Those of us who see that the world doesn't have to be the way it is, should—to the degree we can—help others understand that in profound ways. That is the role that I've chosen to try and take with my art. Other artists might take different paths, you know, I don't think all art is the same. All artists clearly don't make the same choices, but I think that it's a very important and valid choice to cast your lot with humanity.”