Early in her new book about Isabel Rawsthorne, Carol Jacobi steps briefly out of her role as biographer to note conventions that bedevil art historians and biographers alike, particularly when addressing overlooked female artists. “Sex, conception and reproduction are marginalised events in art history, appropriated by biography, or neglected merely as such,” she writes. “They are particularly problematic when the artist is a woman, often set aside as ‘other’ to her art making or incorporated into a reduction of that making to self-reflexive illustrations of her life.”

The event in Rawsthorne’s life that provokes this observation is a newspaper announcement of 1934, that she was “renouncing and abandoning” her birth name of Isabel Nicholas. She would henceforth be known as Margaret Epstein—the name of the actual wife of sculptor Jacob Epstein. Two months later, when Rawsthorne gave birth to a little boy, the baby’s mother was duly noted as Margaret Epstein, wife of Jacob Epstein. Aged only 22, she had effectively erased herself for the sake of another woman.

Isabel Rawsthorne’s Three Fish (1948) demonstrates her fascination with the natural world, particularly marine and bird life

Rawsthorne had been living with the Epsteins for two years, modelling in return for lodgings and studio space. Epstein sculpted vivid Minoan-inspired busts of Rawsthorne, but their creative relationship was reciprocal. Aged only 21, Rawsthorne’s animal studies were shown at the Valenza Gallery and her flower paintings at the Redfern. The two artists painted from the landscape side-by-side (Jacobi notes that some works attributed to Epstein from this period merit “a proper comparative study” with Rawsthorne’s.) But when she became pregnant, it was Rawsthorne who gave up her baby, her name and her relationship with Epstein and left London, penniless, for Paris.

This early episode is emblematic. Throughout her life, this scintillating, forthright and bewitching woman embarked on mutually inspiring partnerships with brilliant men (often more than one at a time). She was embedded in the intellectual life of Paris before and after the Second World War, talking ideas with George Bataille, Jean-Paul Sartre, Walter Benjamin and Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and art with Pablo Picasso, Balthus, André Derain and her great love, Alberto Giacometti. Yet Rawsthorne’s partnerships, begun on equal footing, too often concluded with her left penniless and unmoored again, her studio lost, her work abandoned.

Isabel Rawsthorne photographed by John Everard in 1933

“Isabel’s long years working on the Left Bank, and her particular associates there, made her by far the most informed of the School of London group”Carol Jacobi

One of the tasks Jacobi sets herself is to demonstrate Rawsthorne’s role in introducing London’s bohemia to art and ideas, artists and thinkers advancing the scene in Paris. “Traditional models of ‘influence’ […] are wholly inadequate for understanding the richness of relations in London and Paris after the Second World War,” Jacobi notes. “The players were individuals rather than masters or disciplines […], Isabel’s long years working on the Left Bank and her particular associates there, not to mention her fluent French, made her by far the most informed of the School of London group.”

Rawsthorne’s correspondence and diaries reveal her wrestling with philosophies of touch and perception, poring over the latest illustrated publications on marine and bird life, and studying William Bedell Stanford’s radical 1942 translation of Aeschylus. As an artist, Jacobi portrays Rawsthorne taking up emblematic questions and themes of her time, and subtly indicates the influence of, for example, her zoological subjects of the late 1940s on the work of those around her.

Isabel Rawsthorne, Migration IV, c. 1970s. © Warwick Llewellyn Nicholas Estate. All rights reserved, DACS 2020.

Jacobi’s decision to focus on Rawsthorne’s intellectual influence in the post-war period is perhaps tactical, since very little of her art made before this point remains. In part this can be blamed on her many name changes. Born Isabel Nicholas, after her brief stint as “Margaret Epstein”, she was married first as Delmer, then Lambert before her union with the composer Alan Rawsthorne in 1954. Poverty, precarity and conflict, however, play an even greater role—work was abandoned along with homes and studios, or destroyed in bombardments. Jacobi describes Rawsthorne and Walter Benjamin as “typical during this period of artists whose reflections on the shocks and discontinuities of modern times were themselves preserved only in provisional and discontinuous forms”.

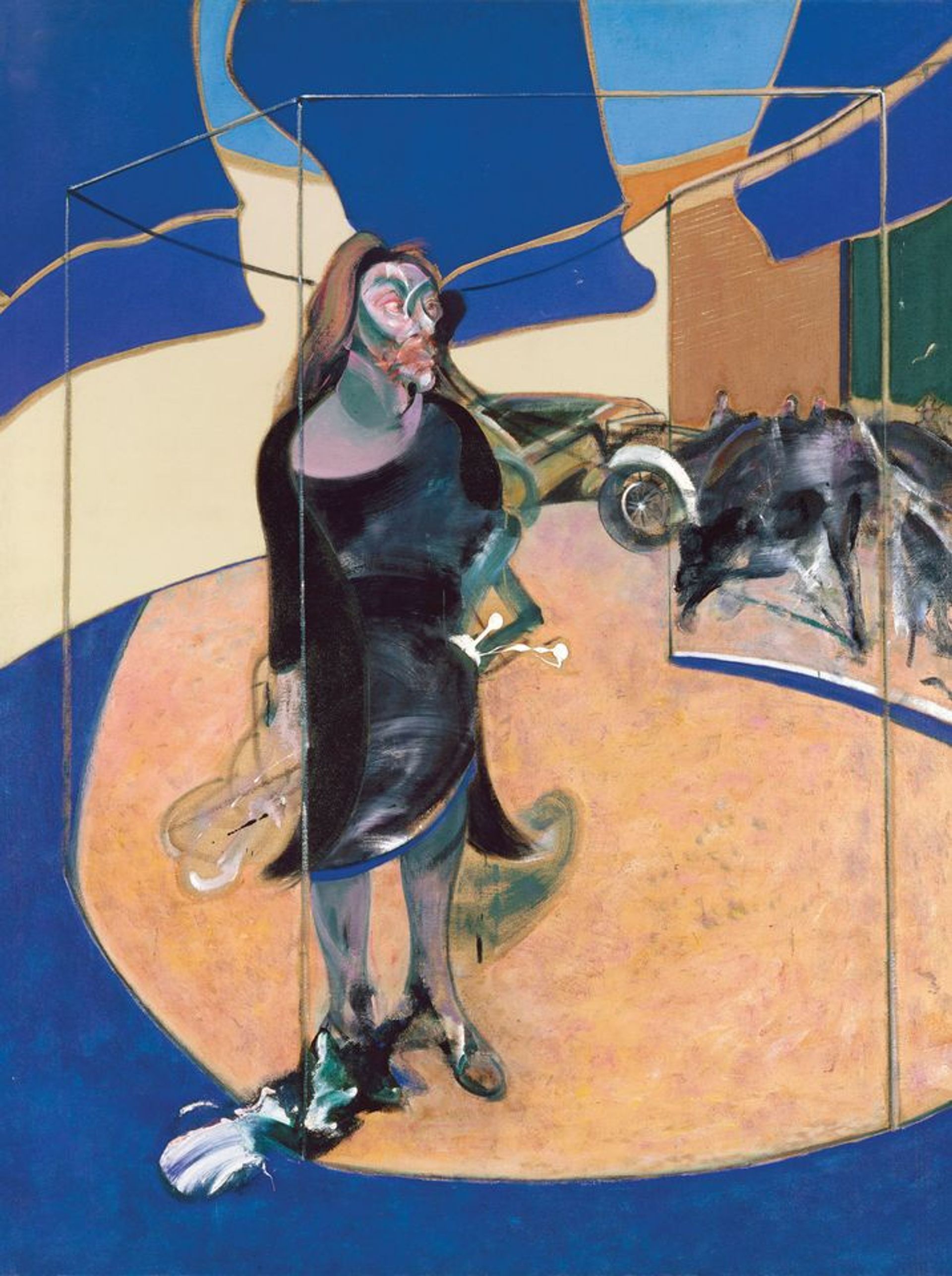

Rawsthorne’s social circle in London after the war included Francis Bacon, with whom she became close. Theirs, again, was a relationship of mutual respect: he understood her exploration into veiled, uncertain perception, her desire to paint a figure as though it were on glass, at once both definitely there and insubstantial. Bacon’s many depictions of her over the years include the celebrated Portrait of Isabel Rawsthorne Standing in a Street in Soho (1967). Painted the year after Giacometti’s death, Jacobi sees the painting fretted with references to Rawsthorne’s relationship with one of the few artists Bacon revered: from the great sculptor’s walking figures and cube forms, to the car that hit and injured him after he left her hotel in 1938, and, in the charging bull, to Isabel’s own fascination with emblems of Minoan art.

Francis Bacon's Portrait of Isabel Rawsthorne Standing in a Street in Soho (1967) © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS 2020

Rawsthorne’s was a remarkable life, and Jacobi delves deep into her relief, resistance and intelligence work in 1930s Europe, her involvement with anti-fascist propaganda during the 1940s, and her unapologetically colourful love life. (She even appears to have made love with Bacon.) Jacobi’s bigger project here, though, seems to be to reimagine what an artist biography—notably one of a woman artist whose work is largely forgotten—can be. If the tone is less galloping and gossipy than Annalyn Swan’s and Mark Stevens’ recent biography, Francis Bacon: Revelations, published by William Collins, it is because Jacobi treats Rawsthorne’s art with the intellectual seriousness of purpose with which it was conceived. She does not “reduce” Rawsthorne’s art making to self-reflexive illustrations of her life; rather, she addresses the two as richly intertwined.

• Out of the Cage: the Art of Isabel Rawsthorne, Carol Jacobi, Estate of Francis Bacon Publishing in association with Thames & Hudson, 448pp, £30 (hb)