The speculative mania took hold in a niche, previously untapped sector, baffling onlookers as opportunists from afar sought to profit from a bizarre and inscrutable new market. Thousands of businesses materialised almost overnight and enormous sums of money poured into them from investors large and small as talk about “blockchain”, “democratisation” and “tokenisation” wormed its way into mainstream consciousness.

As the market exploded and major corporations began to join the flailing bandwagon, pundits began to wonder whether there was any intrinsic value—or any value at all—underlying the craze; public confidence soon waned as it became clearer that the whole thing was perhaps a bit much. The market deflated and a new generation of disappointed investors were left holding the bag.

Sound familiar? This actually took place in the summer of 2017, when thousands of completely unregulated ICOs (initial coin offerings) began to dominate the newly frothy cryptocurrency markets. Seeing Bitcoin’s precipitous rise, thousands of companies decided to hitch their fortunes to the cryptocurrency’s younger sibling, Ethereum, a self-described “world computer”, which offered the ability to fundraise by minting “tokens”—effectively shares—without regulation, scrutiny or any semblance of a viable product.

“Ethereum was basically a platform for illegal securities”Amy Castor, journalist

Upwards of 80% of the sales wound up being glorified pump-and-dump schemes, with millions made and very little built, and the whole thing eventually fell foul of the US Securities and Exchange Commission. This year, these opportunists have moved onto unregulated pastures new: the world of high art.

It is difficult to overstate just how similar the mania around NFTs (non-fungible tokens) is to the boom of 2017. Over the past few months, many of the same cryptocurrency devotees who failed to realise their dreams of democratising/tokenising/decentralising finance have pivoted entirely to digital art, fuelling another boom that has seen Christie’s auction a digital collage for $69m, a tweet by Elon Musk garnering a $1.1m bid, and toilet paper brand Charmin peddle NFT-monogrammed loo roll. As before, the underlying value of the craze is dubious: “buying” an NFT does not generally confer actual ownership, but rather produces a certificate and a link to a URL of an image that can still nevertheless be viewed by anyone online.

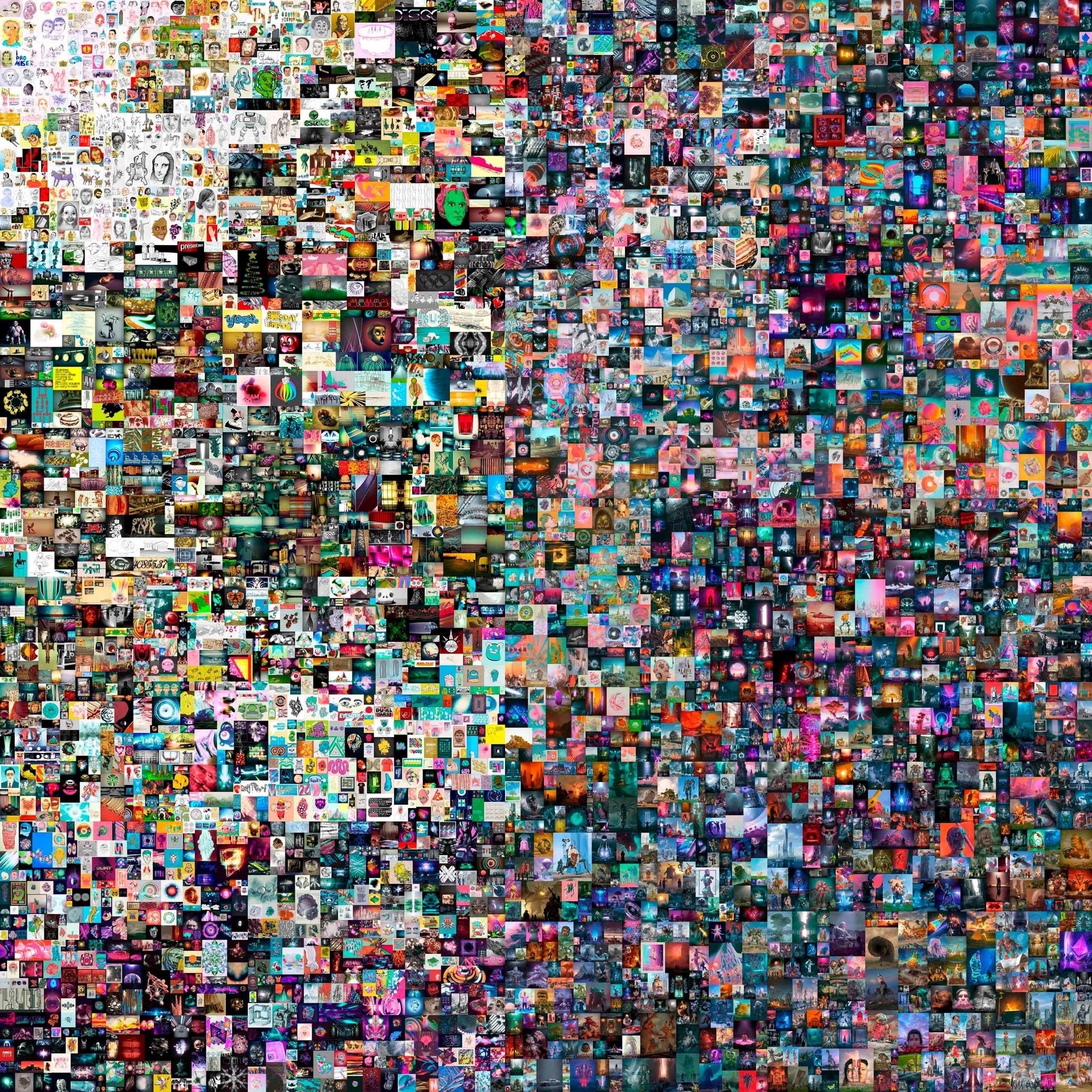

While much of the action taking place in the NFT world has been chalked up in marketing materials as, uncannily, a “democratisation of the art world”, a major portion of the frantic buying is actually fuelled by boosters from the cryptocurrency world, some of whom have used the NFT boom as an opportunity to resurrect their flagging, 2017-era businesses. Take, for instance, the $69m sale by Christie’s of Everydays: The First 5,000 Days by the digital artist Beeple (aka Mike Winkelmann). Of 33 active bidders, 91% were new to Christie’s, and 64 % were either Millennials or Generation Z—buyers who were primarily the newly minted crypto rich, beneficiaries of spikes in digital assets. It also emerged that the pseudonymous buyer, Metakovan, was Vignesh Sundaresan, a long-time cryptocurrency entrepreneur who owns the NFT index fund Metapurse (of which Beeple himself has a 2% stake) and, yes, raised $47.5m in an ICO in 2017. That company’s token, the Lendroid Support Token, now effectively has no value.

Beeple's Everydays: The First 5,000 Days (2021), a non-fungible token minted on 16 February Image: courtesy of Christie's

Beyond Sundaresan, there is a host of other former ICO impresarios trying their luck with NFTs. One-time ticketing service Blockparty, whose own token is circling the drain, rebranded as an NFT music platform. Others to go all in on NFTs include the blockchain companies Theta and Enjin. And it is not only former Ethereum players: the second highest bidder at the Christie’s Beeple auction was the Chinese entrepreneur Justin Sun, the founder of the widely ridiculed Ethereum rival TRON, while Everipedia, a Wikipedia clone on the Eos blockchain network, has rebranded as “Photoshop for NFTs”.

That is to say nothing of the large Silicon Valley corporations sustaining the craze. The colossal venture firm Andreessen Horowitz, which was involved in the 2017 bubble, has heavily invested in the NFT world, most recently putting $23m into the online marketplace OpenSea. Money has also poured in from the Winklevoss twins, Bitcoin fanatics who invested in the enormously influential NFT marketplace Nifty Gateway.

Metakovan’s resumé

Amy Castor, the journalist who uncovered the true identity of Metakovan, described the collector’s resumé as a hodge-podge of all the various crypto-related speculative trends of the past few years, making him representative of an industry that adapts quickly to any new craze that looks profitable. “Ethereum was basically originally a platform for these illegal securities,” Castor says. “The problem was, regulators came down on them, a lot of these people faced fines and charges and the market came apart.”

Ethereum followers then moved into decentralised finance (DeFi), a little understood movement that offered complex, high-risk financial instruments to retail investors. “DeFi was a sort of way to get that going again, but it was really confusing to most people outside of crypto,” Castor says.

NFTs, almost by accident, have become a boom precisely “because people outside of crypto really relate to it”, Castor says. “They can understand the concept of NFTs, which is, ‘Hey, all you artists out there have been having so much trouble making money with your digital artwork, because it’s hard to track these things, but with NFTs you can finally make money’. So people not interested in crypto became interested, and artists saw these things going for millions of dollars and thought, ‘Sure I can get in on this and make money too!’.”

It is not clear whether the NFT movement will bring any future tangible benefits for digital artists, some of whom have produced NFT works of art which are brilliantly weird and creative, and perhaps the whole thing should not be written off entirely. The problem, however, is that to profit from NFTs artists have to first invest in Ethereum (or, in some cases, other cryptocurrencies), a network which has its own cryptocurrency, ether. Buying into the network causes the price to appreciate, benefiting the largest holders. “That’s why NFTs are a real boom for the crypto bros,” Castor says. “They’ve found a new way to bring fiat currency [that is, dollars, pounds and euros] into Ethereum.”

A cynic might argue that these former ICO entrepreneurs are not merely pivoting but have actually stumbled across a new fundraising mechanism, one which happens to fill a conveniently unregulated niche: a way to raise money quickly and efficiently that, unlike ICOs, does not run afoul of US securities laws. The problem in 2017 was that many of these companies were explicitly or implicitly promising returns on investments into their businesses, which made their tokens look a lot like illegal securities. But an NFT does not come with that problem—with the barest amount of effort you can mint a work of art that subsequently sells for thousands. And if it doesn’t resell? Well, nothing can be done, because nobody expected to profit anyway. And, indeed, probably won’t.