Not all two-artist shows are a perfect coupling. The current Calder-Picasso exhibition at the De Young Museum in San Francisco, for example, offers only a faint echo of the revelations provided by Calder Miro at the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC in 2004 (co-organised with the Fondation Beyeler in Basel), although a number of significant pieces by Calder appeared in both. But then, the respective artists’ relationships with each other might explain the disparity in depth between the two projects.

Alexander Calder (1898-1976) and Joan Miro (1893-1983) began a lifelong friendship and correspondence from their first meeting in 1928. Calder and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), though long aware of and mostly appreciative of one another's work, met only four times. The guiding spirits of the De Young’s exhibition—the artists’ grandsons, Alexander S.C. Rower and Bernard Ruiz Picasso—effortfully seek some new common ground in a dialogue printed in the catalogue. But the works on view make a far less convincing, observable case for cross-fertilisation.

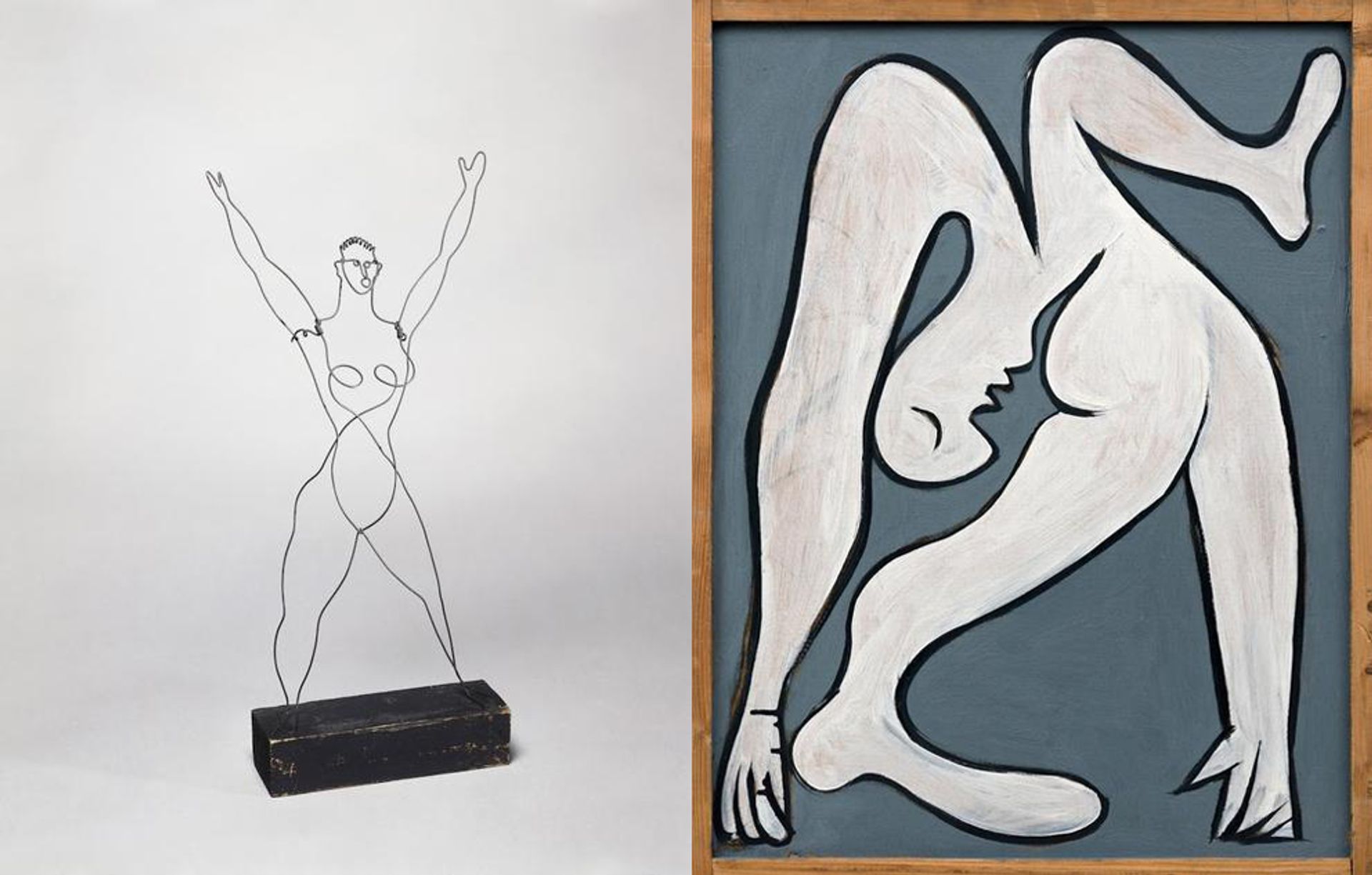

Both Calder and Picasso delighted in the circus, for example, and each responded to it in his work. But placing Calder’s twisted wire Acrobats (1929) alongside Picasso's painting Acrobate (Acrobat) (1930) contrasts far more than it draws close the two artists’ modes of thinking and making. Careful viewers will notice a label’s false claim that a single unbroken line defines the splay of Picasso’s wildly disfigured nude. And those conversant with Picasso's work will know how much more the play of distortion in the painting flows from deeper currents in his own art than from any resonance with Calder’s.

Alexander Calder, Acrobat (1929), and Pablo Picasso, Acrobat (Acrobate) (1930) Photo: courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, and Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso para el Arte, Madrid. © 2020 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo © FABA, Hugard & Vanoverschelde

A couple of items presented confirm that Picasso casually tried his hand at wire work. But as soon as Calder took to the air with dangling, open, wire-contoured portrait heads, precursors of the mobiles, he left even Picasso’s graphic fluency looking sluggish and plane-bound. And those who saw the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art's grand 1998 presentation of Alexander Calder 1898-1976 (a collaboration with the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC) will feel stinted here by the exclusion of all but one hanging wire portrait: Medusa (around 1930).

If you disregard the brittle thematic ordering of Calder-Picasso, which groups works under headings such as “Capturing the Void”, “Vanitas” and “Gravity and Grace”, you will see glimmers of unanticipated interest shine through the power of individual works.

Installation view of 'Calder-Picasso' at the de Young Museum Photo: Gary Sexton, courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Those who know Jasper Johns’s work of the 1980s, for example, will thrill to see here Picasso's Le Chapeau de paille au feuillage bleu (Straw Hat with Blue Foliage) (1936), a Surrealist portrait of his mistress, Marie-Therese Walter, that happened to spark fresh metamorphoses in Johns’s imagery and thinking. And Picasso's bizarre portrait links far more compellingly with other Marie-Therese images on view at the De Young, including Nu couche (Reclining Nude) (1932) and Femme-assise dans un fauteuil rouge (Woman Seated in a Red Armchair) (1932), than with anything here by Calder.

Ignore the thematic scaffolding and the show's survey can be seen to move from comedies of anatomy to comedies of cosmology, tracking Calder’s transition to delicate, ostensibly abstract wire and metal pieces, such as Object with Red Discs (1931) and Croisere (1931), to the wall-mounted Constellations, and ultimately, mobiles that can evoke micro-worlds of plant biology or the shifting order of clouds and orbs. (Here is another free exhibition idea for an enterprising curator: bring Calder's mature works together with Henri Matisse’s “cut-outs”.)

Alexander Calder, Croisière (1931), from the Calder Foundation, New York Photo: Tom Powel, courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. © Calder Foundation, New York. © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; photo courtesy Calder Foundation, New York / Art Resource, New York

Whatever reciprocal influence viewers might detect between Calder’s and Picasso's art, one difference cannot be talked away: their disparate ways of occupying time and place. Picasso's works, no matter how great or influential, belong to their Modernist period, whereas Calder's mobiles always dangle into the present moment of our seeing them in person, their slight shifts and reconfigurations evoking the very breezes of time’s passage. Nothing in Calder's work, or in Calder-Picasso, better exemplifies his stated view that “art must be a physical bond between the varying events of life”.

• Calder-Picasso, is at the De Young Museum, San Francisco, until 23 May. It then travels to the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, 23 June-12 September, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 31 October-30 January 2022