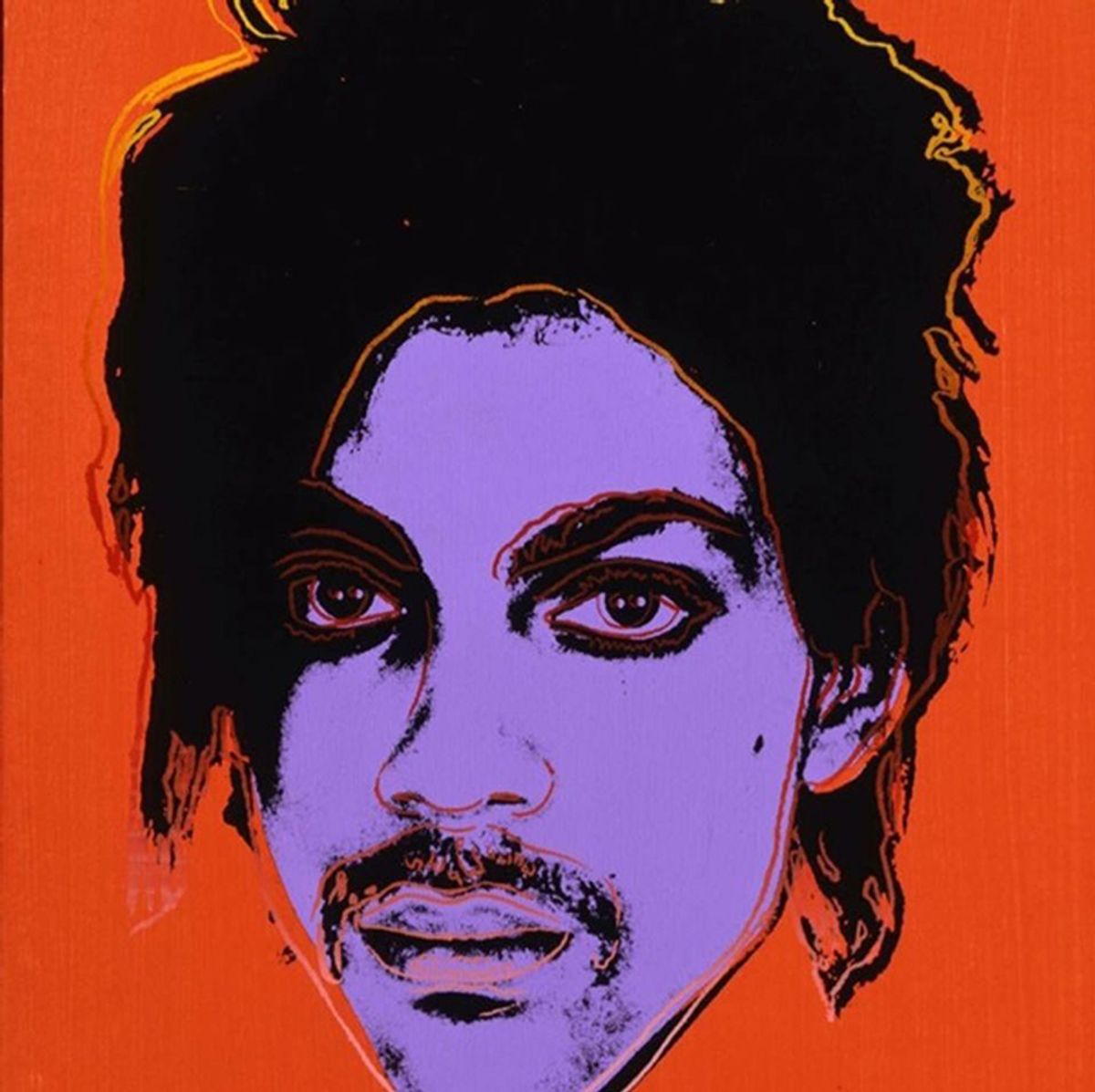

In a potentially game-changing decision, the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit has found that a 1980s portrait series by Andy Warhol depicting the singer Prince did not constitute “fair use” of the photograph by Lynn Goldsmith that it was based on.

The 26 March ruling by the three-judge panel in New York tempers the Second Circuit’s controversial 2013 decision in the case Cariou v. Prince, when it decided that most of the works in a series by the artist Richard Prince lawfully incorporated photographs by Patrick Cariou. Under that ruling, the key to fair use by another artist is whether the second work is transformative of the first, by conveying a new meaning or employing a different aesthetic. In its new decision, the court makes clear that these factors alone are not enough to protect an artist from an infringement claim.

“The implication of Cariou is that almost all appropriation art is fair use,” says the art lawyer William Charron. The Warhol decision is a warning that appropriation artists and those who license their work should proceed cautiously, he says.

The latter case involves a 1981 photograph that Goldsmith licensed to Vanity Fair in 1984 to be used as source material. Vanity Fair in turn commissioned Warhol to create an illustration of Prince for an article. Unbeknownst to Goldsmith, however, Warhol created 15 other artworks based on the photo. The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts owns the copyright to these works, which it licenses to others.

Goldsmith learned of Warhol’s series after Prince died in 2016 and one of them appeared on a magazine cover published by Condé Nast, which had licensed it from the Warhol Foundation. Goldsmith and the foundation sued each other, with Goldsmith arguing that the series infringed on her copyright and the foundation asserting that the series constituted fair use.

A lower court ruled against Goldsmith in 2019. Applying Cariou, it found the Warhols had a “different character”, “new expression” and “new aesthetics” distinct from Goldsmith’s, and transformed Prince from a “vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure”. Each of the works is “immediately recognisable as a ‘Warhol’ rather than a photograph of Prince”, that court found.

“That was error,” the Second Circuit says. “Whether a work is transformative cannot turn merely on the stated or perceived intent of the artist or the meaning or impression that a critic–or for that matter, a judge–draws from the work.” Otherwise, “the law may well recognise any alteration as transformative.”

It is “entirely irrelevant” that the Warhols were recognisable as such, the court adds. “That logic would inevitably create a celebrity-plagiarist privilege; the more established the artist and the more distinct that artist’s style, the greater leeway that artist would have to pilfer the creative labours of others.” The ruling returns the case to a US District Court in New York for additional proceedings.

The lawyer for the Warhol Foundation, Luke Nikas, said his client “strongly disagrees with the Second Circuit’s ruling” and will challenge the decision. He declined to say whether that challenge includes an appeal or the litigation of other potential defenses in the lower court.

Goldsmith said in a statement, “I fought this suit to protect not only my own rights, but the rights of all photographers and visual artists to make a living by licencing their creative work.” Her lawyer declined to comment further.

In its decision, the Second Circuit compares Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s photograph to a film director’s use of a novel. Even though The Irishman is recognisably a “Martin Scorsese”, that does not absolve the director from the obligation to licence the book it is based on, it says.

To be truly transformative, “the secondary work itself must reasonably be perceived as embodying an entirely distinct artistic purpose, one that conveys a new meaning or message entirely separate from its source material.” However murky that construct, the court seemed to have no difficulty applying it to this case. The works have an identical purpose, it says: “They are portraits of the same person.” Although Warhol’s signature style may give a different impression of Prince, the photograph “remains the recognisable foundation”, it adds.

Another aspect of fair use, the impact of Warhol’s works on the market for Goldsmith’s images, also favoured the photographer. The foundation and Goldsmith have both sought to licence their depictions of Prince to magazines with an overlapping customer base, the court notes, and actual and prospective damages to Goldsmith may be substantial.

How will the Warhol decision affect other lawsuits alleging infringements on artistic copyrights? “Every case will still turn on each work of art and the market,” says Charron.